views

When China commenced its coercive and aggressive posturing at the LAC in Eastern Ladakh in April 2020, it was against the run of play that we witnessed a downturn in Sino-Indian relations. Just six months prior, President Xi Jinping had come calling at Mamallapuram, a coastal town of Tamil Nadu, as a sequel to PM Narendra Modi’s Wuhan diplomacy.

Clearly, perceptions changed quite drastically in those six months, or they were already set to change before Xi Jinping decided to return Modi’s call.

Two interesting things had happened in the short period of three years prior to April 2020. The Doklam standoff of 72 days in 2017 had surprised China. It ended at China’s initiative because Xi Jinping could ill-afford to have a border standoff festering with a member of BRICS even as the BRICS summit was being conducted at Wuhan. The 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party followed shortly thereafter and this understanding applied there too.

Relations between India and China have been on a downhill since April 2020 and 15 rounds of border talks have failed to go beyond the areas of Pangong Tso and Gogra to bring about a restoration of the LAC. China has hedged all along in an attempt to coerce India.

In fact, the triggering of the April 2020 crisis, too, is ascribed primarily to the rising strategic confidence of India, especially over the last eight years or so when India started to assert itself to secure its interests a little more robustly and energetically. China wished to dent this rising confidence, especially after India published maps showing the entire Gilgit Baltistan, PoK, and Aksai Chin as part of India.

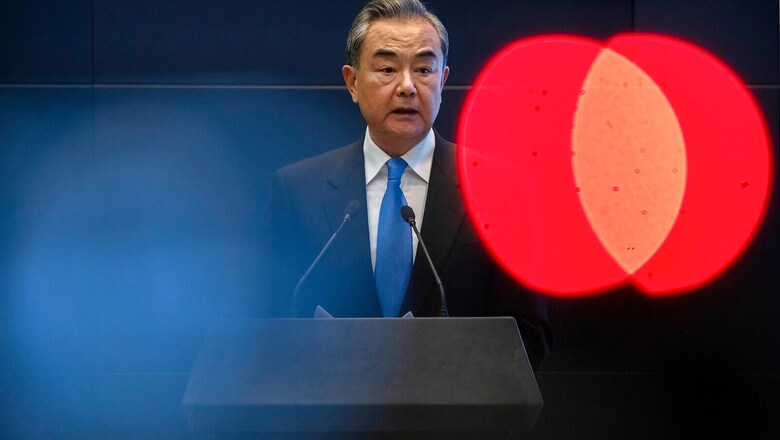

So, what has changed now which prompted Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to visit India at short notice, just after he addressed the Organisation for Islamic Cooperation (OIC) in Pakistan; a gesture expectedly never appreciated in India?

ALSO READ | Wang Yi’s India Visit Not Impromptu, Signals a Churn Triggered by Nato-Russia Conflict

The war in Ukraine which has seen India remaining neutral, is also seen to be changing the dynamics of the world order in the post-Afghanistan and post-Covid times in ways that China has much less control over. China has itself maintained a largely neutral stance which is skewed in Russia’s favour. It has probably concluded that India gives higher priority to its relationship with Russia to neutralise the possibility of greater tension with China along the northern borders.

The strategic partnership with the US is important for India in the context of the overall ‘not so friendly’ rise of China in the context of the Indo-Pacific but it’s the continental threat to its land borders which it perceives of far greater importance. Yet China also realises that India is a swing state and with its rising potential could add much to the Russia-China equation.

Geo-strategically, the expanse of the Indian Ocean, so crucial for China’s own sustenance and economic status, is in India’s proximity. Future groupings would dictate the various security nuances of the Indian Ocean. China is fully aware that Western efforts are afoot to wean India away from its dependence on the Russian supply chain of military equipment and arms.

If that succeeds in the long-term, India could securely and surely be committed to the US side which would tilt the balance of power substantially. It’s not as if China is realising that it erred in driving India more firmly into the US camp. It is only seeking to ease tension with India to prevent an early exit of India to the ‘other side’.

Perhaps there is a growing realisation within China that the actions it undertook in April 2020, in the wake of the pandemic, were in haste and do not serve its interests. The subsequent events in Afghanistan and now in Ukraine have altered the scenario of the new world order over which China has little control. It is now seeking to gain some semblance of control through measures that it has not yet thought through. In most ways, it is probing for a response from India. It is in no hurry to respond to Indian demands either.

There are, however, tactical reasons too for this sudden turn around. There is another BRICS summit coming up in China in 2022, for which it wants the presence of PM Narendra Modi. This is being preceded by a planned Russia-India-China (RIC) summit. An Indian attempt to play all this down will be seen as a boost for the West. Full attendance would add flavour to the Russia-China equation. China’s aspirations will be met if it is seen to influence a full conference of BRICS.

Wang Yi has, of course, made the cardinal error of coming to India via the Pakistan and Afghanistan route, despite being fully conscious of India’s sensitivity to any hyphenation with Pakistan. Perhaps it’s a level of desperation which resulted in China adopting this option. After treading on Indian toes with his statements at the OIC, Wang surely had the temerity to arrive in India to make peace overtures. India was not expected to respond enthusiastically and it did not either.

ALSO READ | China is India’s Threat No.1, Wang Yi Visit Just a Strategic Pause in Beijing’s Campaign of Aggression

The fact that the Chinese Foreign Minister has not been shown any warmth by the Indian side reflects the state of relations. India cannot be cowed down. It has ensured mirror deployment of force levels at the border and proven that coercion will not work. The bottom line which has been read to Mr Wang Yi is that first the unnecessary aggression of the PLA has to stop and troops must pull back to original positions (something always difficult to define to the Chinese).

Indian National Security Advisor (NSA) Ajit Doval stated: “The two countries need to continue positive interactions at diplomatic and military levels for restoration of peace and tranquility, which is a prerequisite for normalisation.”

Resolving the border tension first was India’s clear message. India must realise its own rising geo-political significance and work towards managing threats to its borders and its internal security. Notwithstanding overtures from different big powers which will progressively increase in the future, India must keep steadfast focus on developing its comprehensive strategic capability.

As the world looks towards rapidly changing geopolitics in view of the challenging situations thrown up in the last three years, India has to determine its own interests and based upon those draw up the equations it needs to work upon. It cannot keep responding to the tactical gestures of China’s Foreign Office. It’s our interests and only our interests which must remain foremost.

The writer is a former GOC of the Srinagar-based 15 Corps and Chancellor, Central University of Kashmir. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinion News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment