views

Preparing for the Debate Speech

Understand how debates work. You will be given a debate topic – this is called a “resolution." Your team must take a stance either affirmative or negative to the resolution. Sometimes you will be given the stance, and sometimes you will be asked to take a position. You may be asked to stand affirmative or negative. In LD (Lincoln-Douglas debate), the first affirmative speech will be at most 7 minutes long, and the first negative speech will be at most 6 minutes. The speakers then present arguments against the earlier affirmative or negative speech that was just read. Speakers must listen carefully and be able to counter arguments. There are two segments involving cross-examination (CX), in which the debaters are allowed to ask questions and openly debate the topic. This is most often called cross-examination, or cx for short, and occurs after the first affirmative speech, and the first negative speech. The best thing you can do to better understand LD/PF/Policy debate is practice and research.

Research the topic very thoroughly with credible information. Because you may be asked to work on either side, in addition to preparing one speech, you must spend time thoroughly understanding all aspects of the resolution in order to write a second speech. Brainstorm the topic, and research it before you sit down to write. Write out a list of key components for both sides of the issue. If you are on a debate team, do this together. Each member could discuss the key component list, in order to figure out which issues you want to cover in each speech. Spend some time at the library or on the Internet using credible sources to research the key reasons that seem strongest. Use books, scholarly journals, credible newspapers, and the like. Be very cautious about unverified information bandied about on the Internet. You will also want prepare to deal with the strongest arguments your opponent(s) might make. Ignoring the other side’s best arguments can weaken your rhetorical appeal.

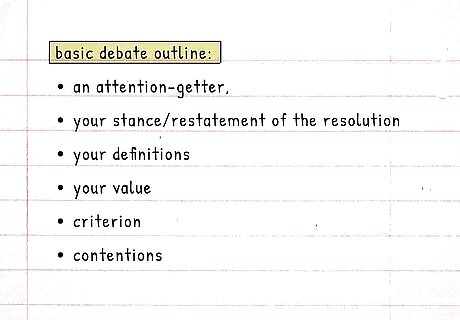

Write an outline of your speech. If you create a basic outline of the speech, your writing organization will probably be better when you actually sit down to write the speech in full. It’s a good idea to memorize the ultimate speech or just rely on the outline as notes when giving it. A basic debate outline should contain six parts: An attention-getter, your stated stance (aff or neg)/ restatement of the resolution, your definitions, your value, criterion, and contentions. You can break each of those six parts into subcategories. It’s often a good idea to write the contentions last, focusing on the value and criterion to hold it up first.

Writing the Debate Speech

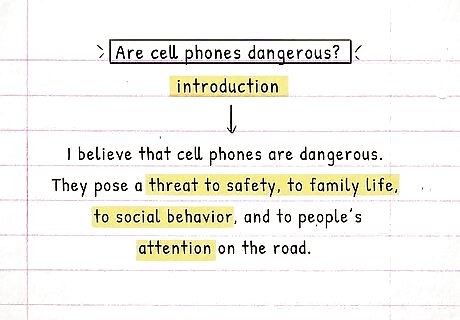

Write an introduction that is catchy and interesting. You want to introduce your topic very clearly and concisely right at the beginning of the debate speech. However, you should open with a colorful flourish that foreshadows the topic. You should address the jury or audience with formal salutations. For example, you could say something like, “Good morning, ladies and gentlemen.” Debates are very formal in tone. Making a good first impression with the judges is very important. This leads judges to assume the debater is persuasive. One technique to write a strong introduction is to contextualize the topic, especially in relation to real world events. Introductions can also focus on prominent examples, quotations, or on a personal anecdote that can help establish a rapport with the audience and judges. Be careful using humor; it involves risks and can lead to awkward silences if not done right. Find a relevant specific that illustrates the underlying point.

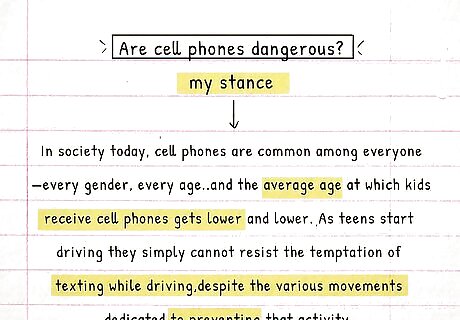

Outline where you stand very clearly. The audience and judges should not have to puzzle over where you stand on the topic. Are you affirmative or negative to the resolution? Say - clearly and concisely and firmly. Up high. Don’t muddle your position. It needs to be extremely clear whether you affirm or negate the resolution, so don’t hem and haw and contradict yourself. The audience also should not have to wait until the end to find out. Make your stance very clear, and do it early on For example, you could say, “my partner and I firmly negate (or affirm) the resolution which states that unilateral military force by the United States is justified to prevent nuclear proliferation.”

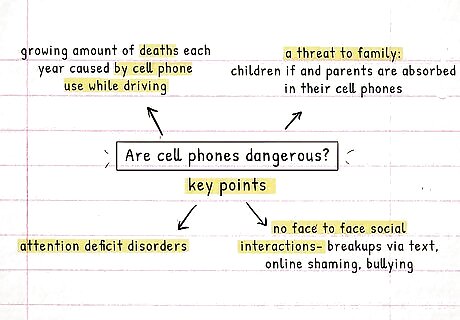

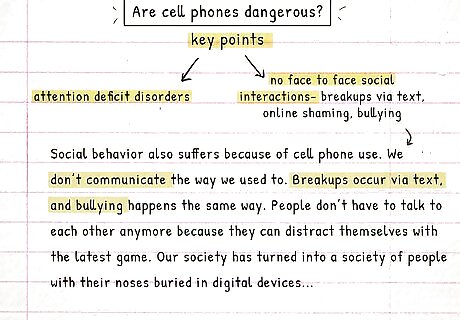

Make key points to back up your stance. You want to highlight your key points very strongly early on in the speech. You could provide rapid-fire examples, basically piling up the evidence to support your stance. A good rule of thumb is to back up your position with 3-4 strong points of supporting argumentation. You definitely need to have more than 1 or 2 key points to back up the stance you have taken. The body of the speech – the key points and their development – should be, by far, the longest part of the debate speech (perhaps 3 ½ minutes to 30 seconds for an opening and for a conclusion, depending on the rules of the debate you are doing).

Develop your key points. You want to back up the key arguments you are using to justify your position. Back every single one of your key points up with examples, statistics and other pieces of evidence. Flesh them out. Focus on the causes of the problem, the effects of the problem, expert opinion, examples, statistics, and present a solution. Try to use visual images, not just generic terms – show don’t tell, and illustrate a point with details. Appeal to the motives and emotions of the listener with a light touch. Appeal to their sense of fair play, desire to save, to be helpful, to care about community, etc. Ground examples in how people are affected. Try using rhetorical questions, which make your opponents consider the validity of their point; irony, which undermines their point and makes you seem more mature and intelligent; simile, which gives them something to relate to; humor, which gets the audience on your side when done well; and repetition, which reinforces your point.

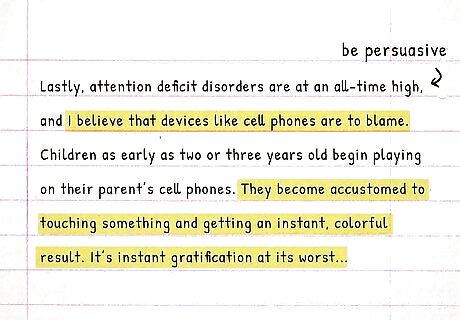

Understand the art of persuasion. Ancient philosophers studied the art of persuasion, and understanding their techniques will help your debate speech. Aristotle believed that speakers were more persuasive if they combined elements of logos (persuasion by reasoning) with pathos (having an element of emotional appeal) and ethos (an appeal based on the character of the speaker) - for example, that they seem intelligent or of good will. There are two ways to use logic – inductive (which makes the case with measurable evidence like statistics or a specific anecdote or example) and deductive (which makes the case by outlining a general principle that is related to the specific topic to infer a conclusion from it - as in, I oppose all wars except those involving imminent self defense; thus, I must oppose this one because it's a war that was not in imminent self defense, and here's why). Or the reverse. You should use pathos sparingly. Emotional appeal on its own can be dangerous. Logos - the appeal to reason - should be at the core. However, logical appeal without any pathos at all can render a speech dry and dull. Consider what you are trying to make your audience feel. Explaining how a topic affects real people is one way to use pathos well.

Concluding the Debate Speech

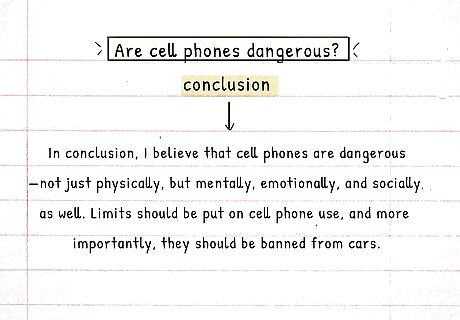

Write a strong conclusion. At the end, you should reiterate your overall stance on the topic to reinforce your position. It’s a good idea to conclude with your intention to do something and with a strong appeal for action as well. One strong way to conclude a debate speech is to bookend the conclusion with the opening, by referring back to the introduction and tying the conclusion into the same theme. Quotations can be a good way to end a speech. You can also end with a brief summation of the key arguments of the speech to ensure they remain fresh in judges’ minds.

Work on your delivery from beginning to end. An advanced speaker carefully hones his or her delivery. The speaker understands the power of carefully timed rhetorical pauses and pays careful attention to the desired tone (firm, moderate, etc.) You don’t want to read a debate speech verbatim. Although you want to memorize the speech, and may use notes or your outline when giving it, it needs to sound natural and not too rehearsed. The key to giving a good debate speech is research. You will need to think on your feet to counter opposing arguments. Use a clear, loud voice, and be careful to watch pacing. You don’t want to speak too loud or too slowly. Remember that confidence goes a long way toward persuasion.

Comments

0 comment