views

Anyone who has taken an Uber, sent a Slack message or enjoyed a free beer at a WeWork owes a little something to Masayoshi Son.

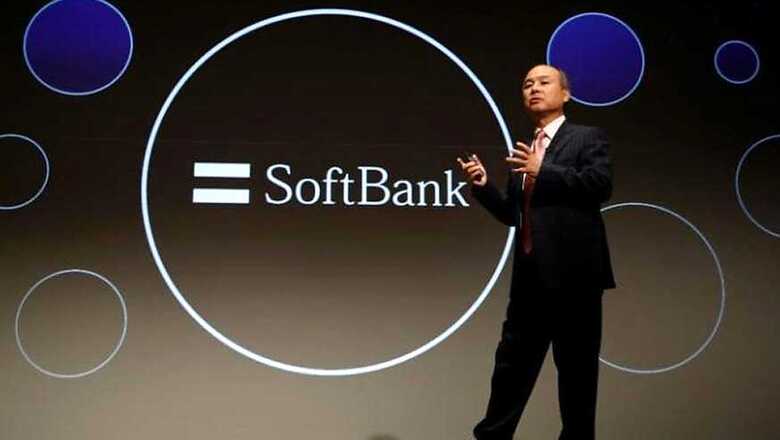

Through his Japanese conglomerate SoftBank and a $100 billion investment fund, Son plowed huge sums into these and other companies that aim to change how people work, travel and live. His investments enabled the young companies to throw caution to the wind and run up big losses as they expanded at a breakneck pace in recent years. Even in the startup world, where idealism is abundant and losses are a badge of honor, Son’s approach and ambition stood out.

His early bet on Chinese technology giant Alibaba earned a return of more than $100 billion and cemented his reputation as a farsighted investor. He has outlined a 300-year plan to make SoftBank a leader in artificial intelligence, robotics and other advanced technologies.

But this year, his grand designs collided with reality.

In what may turn out to be a reckoning for Son, Wall Street has started running from companies backed by SoftBank and its Vision Fund. The chief executive of WeWork stepped down this week after a botched initial public offering. Uber’s stock has fallen nearly 30% from its IPO price in May. And shares in Slack, which provides a workplace messaging service, have tumbled more than 40% from their first day of trading in June.

SoftBank’s critics said its investments have poisoned the ecosystem for young companies by encouraging founders to take excessive risks with little regard for building businesses that can last through the ups and downs of the economy. They are hoping the WeWork debacle will force investors to be more skeptical about fast-growing companies. Even Son has acknowledged that the businesses his company invests in need to become financially sustainable more quickly.

“I’m hoping this is the tipping point that brings more sanity into the capital markets,” said Len Sherman, a former senior partner at Accenture who is now an adjunct professor at Columbia Business School.

SoftBank and the Vision Fund now face the prospect of harsh write-downs on some of their investments. WeWork and its advisers considered selling shares in its public offering at a valuation as low as $15 billion, well below the $47 billion valuation at which SoftBank last invested in the company in January. If the stock market does value WeWork at $15 billion, SoftBank could be forced to take a $2 billion loss on its investment in the office space business, according to analysts at Bernstein.

The prospect of such sizable losses has cast a cloud over SoftBank and raised doubts about Son’s investment style. And that, in turn, could undermine his effort to raise an estimated $108 billion for a second Vision Fund. SoftBank said in July that it expected Apple, Microsoft and other companies to contribute to the new fund, but the most important investors in the first fund — Saudi Arabia, and Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates — have yet to commit to it. (Apple declined to comment on the fund, and a Microsoft spokesman said the company’s participation had not changed since the July announcement.)

A spokeswoman for SoftBank declined to comment.

Speaking to executives of companies backed by the Vision Fund last week at the Langham Hotel in Pasadena, California, Son said they needed to be able to bring in enough revenue to more than cover expenses within a few years of going public, according to a person who attended the event but was not authorized to discuss it.

Simply increasing sales is not sufficient, Son said in what people in the audience understood as an implicit reference to WeWork.

Son, 62, built his business empire on huge bets and an unshakable belief in his own convictions. One frequently told story about him is that he once threatened to set himself on fire in the offices of a Japanese telecom regulator unless policymakers gave him what he wanted. He was one of the first corporate moguls to visit President-elect Donald Trump in 2016, promising to invest $50 billion and create 50,000 jobs in the United States. (The pledge was based on investments that SoftBank had already planned to make.)

Born to a family of Korean descent, he grew up in Japan and studied computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, where he made his first foray into business — creating an electronic translator that he sold to Sharp.

He started a computer parts shop in Tokyo called SoftBank in 1981 and built it into a technology and telecommunications conglomerate. His wealth swelled during the dot-com boom, withered in the early 2000s and slowly recovered as SoftBank became one of Japan’s biggest cellphone companies.

In 2000, Son put $20 million into Alibaba, a stake that is now worth nearly $119 billion even after SoftBank sold off some of its shares three years ago. That windfall also helped pump up Son’s personal net worth to an estimated $20 billion.

Son has sought to duplicate his Alibaba investment again and again.

“You cannot think small,” he told analysts in May 2017. With the prospect of what he called a “gold rush” in the tech industry, now was the time to “open up our mind, open up our heart and think big.”

The Vision Fund has hit some home runs. The fund earned a roughly $1.5 billion return on its 2017 investment in Flipkart when Walmart acquired that business last year. Despite missteps like WeWork, the fund might need only a few bets that pay off big to make up for losses elsewhere, said Tom Nicholas, a professor at Harvard Business School.

“That said, when you invest at high valuations — as SoftBank is prone to doing — it puts a lot of pressure on the fund to generate truly outsized returns from the successful portfolio investments,” Nicholas said in an email.

Several of Son’s investments have been disappointments, including one of SoftBank’s biggest forays into the United States: the 2013 acquisition of a controlling stake in Sprint, the struggling wireless company.

Son paid $21.6 billion and took on billions more in debt to buy the company. But he predicted that SoftBank would help Sprint overtake its bigger rivals, Verizon and AT&T, in part by upgrading the company’s network to deliver the better services and faster speeds.

Yet that promise remains just that. Excluding accounting changes that lifted Sprint’s earnings, the company’s bottom line has stayed roughly flat under SoftBank, said Craig Moffett, a research analyst at MoffettNathanson. Sprint has not only fallen further behind its bigger rivals but also lost ground to T-Mobile, a smaller competitor.

“It’s been a terrible investment,” Moffett said.

Son tried several times to combine Sprint with T-Mobile. Only last year did SoftBank finally strike a deal by agreeing to sell Sprint to T-Mobile, a deal that 18 attorneys general are seeking to block.

That deal is crucial to Sprint’s survival, Moffett said. “There’s a very solid argument that Sprint’s equity is worthless if the merger doesn’t go through,” he said.

Several of SoftBank’s more recent investments have also struggled.

Analysts say one of the biggest problems for the company is that its enormous investments in startups have pushed up valuations for young companies to levels that no other investors are willing to pay.

WeWork is a prime example. Son first agreed to invest in that company after a 2016 meeting with its founder and chief executive, Adam Neumann, that lasted less than an hour. In January of this year, the last time SoftBank invested in the office-space company, the two sides agreed to value the company’s shares at $47 billion, up from the $20 billion they said the business was worth in 2017.

Another major flaw with SoftBank’s approach, critics say, is that it imposes few constraints on founders of the companies it invests in. Corporate governance experts were aghast when they learned of some of the conflicts of interests at WeWork that Son and SoftBank tolerated. For example, the company rented space in buildings partly owned by Neumann. (The stakes were later assumed by a WeWork affiliate.)

Son’s chosen startups may also lack discipline because he lavished hundreds of millions or billions of dollars on them before they had even figured out what customers really wanted and how to turn a profit, said Bill Aulet, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management. “Hungry dogs hunt best,” he said.

Peter Eavis and Michael J. de la Merced c.2019 The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment