views

New Delhi: First elections in the newly created state of Jharkhand were held in early 2005. A hung house triggered intense jostling for government formation.

After Jharkhand Mukti Morcha leader Shibu Soren failed to prove majority on the floor of the House, elected BJP lawmakers met in Ranchi in the second week of March to choose their leader.

Three top leaders from Delhi flew in to oversee elections in the BJP legislature party in the Jharkhand assembly. Rajnath Singh, the then general secretary in-charge of the state, was accompanied by Venkaiah Naidu and Sanjay Joshi.

Amid claims and protests by Babulal Marandi supporters, the legislators were told that the party was in favour of nominating Arjun Munda for the top job. Some MLAs, including one Pradeep Yadav who was a close aide of Marandi, pressed for a division. Despite objections, the central observers came out of the meeting to announce Munda’s unopposed election as the chief minister of the state.

That meeting in BJP’s annals may now appear a mere blip in party’s meteoric rise in Indian politics in three decades. But the sequence of events was a manifestation of institutionalisation of ‘high command’ culture in the party ‘with a difference’. Redux of this sequence of events was played out in Dehradun two years later when Bhagat Singh Koshyari's claim for chief ministership was overlooked in favour of B C Khandoori, who was said to be the choice of party high command.

Like most things in Indian politics, the concept of intervention or guidance by the central leader or ‘high command’ first gained currency in Congress’s working culture. It happened within a decade-and-a-half of the first general elections; and can be seen as sui generis metamorphoses of a mass base organisation which led the fight for Independence from the British to the party in power governing the country.

Political power and its sharing engenders disputes — ideological and otherwise. Congress leaders in their plaints to Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri and later Kamraj by mid-60s had started to seek intervention from the central leadership to settle internecine quarrels.

The process was customised by Congress leaders competing to command a loyal support base in provinces. Political patronage and protection was offered in lieu of loyalty and support.

However, the Congress, till late sixties, continued to display some semblance of intra-party democracy. Holding election to choose chief ministers from the elected legislators — both through open or secret ballots — was a common practice. Even organisational elections were held on time and were keenly contested.

Uttar Pradesh strongman Chandra Bhanu Gupta, for instance, could never beholden himself to either Nehru or Shastri. But Gupta, not once but thrice, managed to pip his rivals to take oath as UP chief minister. He could pull it off on the strength of his support base in the organisation. So much so that on one occasion Gupta forced the high commands to nominate a rank outsider like Sucheta Kriplani as the UP chief minister. The election of Acharya Kriplani's wife was seen as a snub to Nehru by the Gupta group. Kriplani, a Gandhian socialist and a trenchant Nehru critic, had quit Congress after Independence to form his own political outfit, though wife Sucheta remained in the party.

Even Indira Gandhi’s elevation as the Prime Minister after Shastri’s death was keenly contested in the Congress parliamentary party by Morarji Desai.

Indira Gandhi’s ascension and marginalisation of the Syndicate legitimised fealty as statecraft in Indian politics.

Babulal Marandi quit BJP in 2006 to launch his own political outfit. He along with Karia Munda, Jual Oram and Nand Kumar Sai was part of the first generation of tribal leaders nurtured by the RSS.

In the last six years, the BJP also attempted to experiment with a new type of leadership in states, including in Jharkhand, by anointing chief ministers from non-dominant communities.

The party continued to get high approval ratings at the national level but faltered in state polls. Dominant caste groups seeking a larger share in power structure have pushed back. In Haryana, the BJP is now dependent on a regional party to run the government. It has had to abdicate power in Maharashtra and Jharkhand.

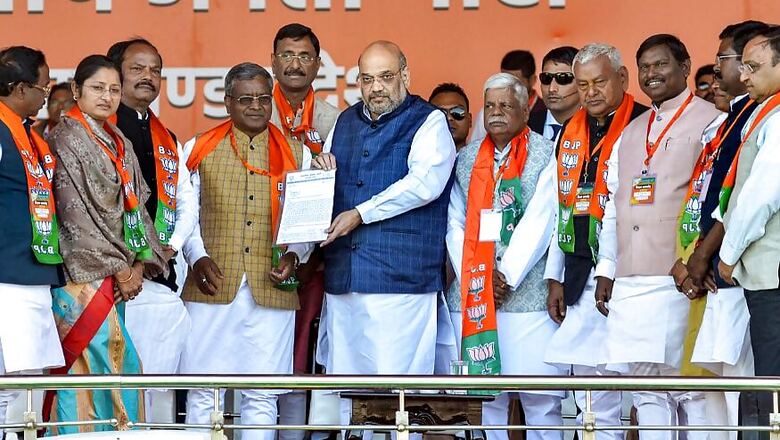

Marandi’s return to the BJP is perhaps the first sign of a course correction in the party.

It is also a testimony to the fact that leaders who continue to represent or cater to a constituency in a certain political ecosystem manage to survive a long spell without power. Just as Babulal Marandi has survived to fight another day.

Comments

0 comment