views

With just a few hours left for counting in one of the most viciously-fought poll battles in Bengal in recent times, it's perhaps the right time to assess what is at stake for Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, politically and otherwise.

A month before polls were announced, things looked bright for Banerjee and her party. The Saradha ponzi scam seemed nowhere around. The opposition looked feeble. The Left was in disarray and the Congress no better. The BJP had clearly failed to cash in and improve upon the support it had received from people of the state in the 2014 general elections. With virtually no political challenge before it at that point, the Trinamool Congress had already decided on the agenda it would pursue - development.

But then a few things happened.

First, two of the unlikeliest parties joined hands. The Congress was more forthcoming and wanted a formal alliance. The Left was tentative. Aware of its acrimonious past with the Congress in the state, it was keener for an informal handholding at the grass roots. But what was common to both parties was their desperate bid for political survival against the allegedly fiendish attacks of the ruling establishment. In the end, the two camps shared seats and avoided a four-cornered fight. For Mamata Banerjee, whose vote share in the 2011 polls was 38.1%, a notch below the Left's 41% (but then she had Congress as her partner and the total vote share of Congress and Trinamool was about 48.5%) this was bad news.

Shortly afterwards, 12 Trinamool leaders were exposed, allegedly accepting bribes in return for government favours, by a sting operation conducted by a Chennai-based media house. Five of them were the party's candidates in the state polls.

While Banerjee was grappling for an honourable exit from that slur, an under-construction flyover collapsed and snuffed out the lives of 27 unsuspecting people in Kolkata. Suspicion that adulterated material was used at the site singed the party yet again.

The Election Commission, as many in the Trinamool Congress describe it now, "wreaked havoc" when it reshuffled the state machinery by transferring more than 50 top officers of the civil administration and police. An unprecedented 714 companies of central paramilitary troops were deployed to ensure free and fair polls over the seven phases earmarked for the state - making a commentary on the state of law and order in Bengal, needless to say.

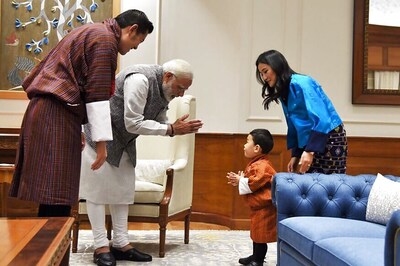

Both Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Congress president Sonia Gandhi, people with whom Banerjee was known to have maintained cordial relations, lashed out at her at public meetings and questioned her integrity. That too was a first of a kind experience for the Bengal Chief Minister who was flaunted by her party as a "symbol of honesty" in the previous elections.

But most of Banerjee's energies were possibly spent on countering the onslaught of a section of the media which ran a sustained campaign against her Ma Mati Manush government. The bitter war of words heightened during her first tenure as chief minister, and during the run-up to the polls it has been vicious like never before.

Livid with the bad press she has had recently, Banerjee suddenly become reticent and imposed a near carpet-ban on interactions with journalists, much to the chagrin of the professionals who find the present elections in the state more intriguing than most elections in the past.

A favourable result for the Trinamool Congress is hence not just an opportunity for the embattled chief minister to answer her critics but also her final chance to stand vindicated on the development course she believes she has charted for Bengal. If not, then it would mean that her model for governance has miserably failed. Numbers would speak, margins would tell more stories. But for Banerjee, challenges would persist. Primary among them would be to ensure that the already vitiated political atmosphere in Bengal doesn’t descend into further chaos.

Comments

0 comment