views

Article 324 of the Constitution of India says that “The Election Commission shall consist of the Chief Election Commissioner and such number of other Election Commissioners, if any, as the President may from time to time fix and the appointment of the Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners shall, subject to the provisions of any law made in that behalf by Parliament, be made by the President.”

Although that sentence is long, it is not particularly difficult to understand. Or so we thought. Recently, the Supreme Court explained what that sentence really means: The Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) must be appointed by a panel consisting of the Prime Minister, the Leader of the Opposition (LoP) in the Lok Sabha and the Chief Justice of India (CJI). And also the captain of the winning team of that year’s IPL.

Okay, I made up the last bit about the IPL. But the rest of it is mostly true. Significantly, the Supreme Court did leave the door open and said that these new rules could be changed in case Parliament makes a law. This might be a concession to the actual text of the Constitution, which says that the appointment is subject to laws passed by Parliament. But with a little cleverer “interpretation” in the future, I am sure there is a way around that as well.

In an ideal world, India’s political parties should have come together to oppose this judgement. Is the Supreme Court merely interpreting the Constitution or writing a new one? But the ruling party is scared. It does not want to be seen as opposing a verdict that supposedly imposes fairness from outside. The Opposition has welcomed the verdict. They see it as a backdoor to power despite losing the last election. Perhaps, they do not feel so confident about the next one. This is why they see no downside in the near future.

All this likely means that the verdict will stand. We folks (in this case, our representatives) were too divided. So someone else will walk away with all the power. You know we have a long memory of this kind of thing happening to our country. So the least we can do is ask some questions.

Is it really more democratic to choose the Chief Election Commissioner this way?

When a larger body makes decisions, as opposed to just one person, it is generally good for democracy. But the larger body must have at least some claim to represent the will of the people fairly. The new judgement puts the Prime Minister at the same level as the LoP. To become Prime Minister, you must have 272 Lok Sabha MPs on your side. To become Leader of the Opposition, you need just 55. And in this new panel, the LoP could come together with the Chief Justice and overrule the Prime Minister by a 2:1 vote. How is this democracy?

But wait! The judgement goes even further. It says that if there is no official LoP, the role shall be played by the leader of the Opposition party that has the highest numerical strength. This means that the bar for sitting on this panel is even lower. In theory, it is set at just one seat. And what happens if no Opposition party meets the threshold of 55 seats, but there are two parties tied at say 35 each? This almost happened in 2014. Will leaders of both the Opposition parties get to sit on the panel? Then the Prime Minister would have just one vote, and the Opposition would have two! They would have twice the votes precisely as a reward for losing the election so badly that neither could get the 55-seat minimum. Still democratic? And who exactly does the Chief Justice represent? Do we dare ask?

Or maybe there is only one seat for the Opposition in the panel. In case of a tie between Opposition parties, perhaps the Chief Justice also has the power to decide which one has been elected more “democratically.” The possibilities seem unlimited.

A whole new constitutional structure?

Article 324 of the Constitution said that the CEC is to be appointed by the President. So far, it was understood that the President acts on the advice of the Council of Ministers. This has been made explicit much earlier in Article 74, which reads: “There shall be a Council of Ministers with the Prime Minister at the head to aid and advise the President who shall, in the exercise of his functions, act in accordance with such advice…”

If the President is now required to act as per the advice of any panel appointed by the Supreme Court, it would appear that we have a whole new Constitutional structure. So we have to wonder. Since the Supreme Court has the power to decide who sits on this panel, could they actually remove the Prime Minister from this panel tomorrow if they wanted? Could the court have created this panel without including the Prime Minister at all? Perhaps they could have made this panel with only Opposition leaders on it, or only judges, or even members of so-called civil society. Would that be legal too?

What other appointments can the judiciary interfere with?

They say this judgement is good because we need the CEC to be non-partisan. I agree with the second part. But why does non-partisan necessarily mean judicial intervention? For that matter, we need people in all sorts of positions to be non-partisan. How about teachers in government schools? Surely we do not want a partisan education system. So should there be a panel in each state to select school teachers, with both judges and Opposition leaders represented on it?

How about doctors? We should ensure that they are non-partisan as well. And then there is the most obvious one, possibly with the most direct impact on our daily lives. We need the local police to be non-partisan. The same goes for every bureaucrat in every government department, from secretaries to the local motor vehicle bureaus. Could the Supreme Court transfer all the powers of elected governments to a panel consisting of various other political parties and judges?

Is our judiciary beginning to resemble a “priestly class?”

The system works when we have checks and balances. If the judiciary can insert itself into the decisions of the executive, then the executive should have a say in matters of the judiciary. The NJAC Bill of 2014 had done exactly this. It had proposed to replace the existing collegium system for the appointment of judges with a National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). Its composition was roughly similar to the format that the Supreme Court considers ideal for selecting a non-partisan Election Commissioner. The NJAC would have senior judges, a representative of the ruling government and a representative of the main Opposition.

And yet, the Supreme Court in 2015 struck down the act that had been passed by Parliament and ratified by 16 state legislatures. So the collegium system stays. Only judges can decide among themselves who their successors will be. Interestingly, the word ‘collegium’ does not appear anywhere in the actual Constitution. It came into existence through a series of Supreme Court judgements “interpreting” the Constitution, culminating in the 1990s. Only the courts have the power to discover hidden meanings in the Constitution. But as with most things involving the judiciary in India, it just takes a few decades to figure out. Today, the inner workings of the collegium are kept secret, of course.

In all of history, a recurring theme is that of the capture of power by something called the “priestly class.” They say that only they can interpret the scriptures. This class gives more and more privileges to itself. The masses cannot easily approach them. And when they do, the process is time-consuming and expensive. Membership in the priestly class is often hereditary. We should at least ask if there are parallels between such a priestly class and the Indian judiciary today. Does the idea of going to court make the common citizen feel empowered or disempowered?

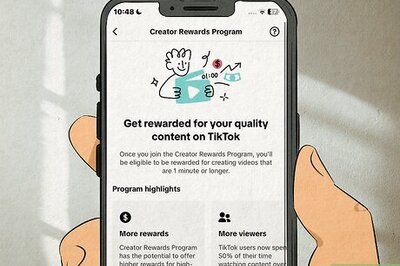

Has the Election Commission been behaving in a partisan manner recently?

Before we go around fixing something, we must ask a more basic question. Is it broken? In other words, has the Election Commission (EC) been doing its job or not? By all accounts, yes. Election campaigns in India have never been more vigorous. Voter participation is up. Despite all the conspiracy theories in the world, electronic voting machines (EVM) have been shown to be perfectly reliable. In 2017, the EC challenged political parties to show how an EVM could be hacked or tampered with. No party even showed up to the event.

In other words, everyone knows that India’s elections are being conducted in a free and fair manner. Additional safeguards such as VVPAT (voter verifiable paper audit trail) have been created. After every election, one booth is chosen randomly in each constituency and the VVPAT slips are tallied with the EVM vote totals. In thousands of booths spread across dozens of elections for nearly a decade, not even one mismatch has ever been found. Then what is the worry?

I know. This is all part of the “democracy in danger” narrative after 2014, isn’t it? The exact opposite is true. Did you know that in 2007, the EC dragged the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) through a series of hearings on whether its recognition as a political party should be revoked? Look up this incident, because it got quite serious. And yet it somehow managed to stay out of the limelight due to a high level of cooperation between the ruling party and narrative makers in the media. Can you imagine if that were happening to the main Opposition today? For that matter, as a candidate from Varanasi in 2014, Narendra Modi was not allowed to address a single rally in the city. The EC always found a reason to say no to him.

This kind of thing no longer happens today. Rahul Gandhi recently went to Lal Chowk in Srinagar and raised the Indian flag there. When Sushma Swaraj, Arun Jaitley and other BJP leaders had tried to do the same in 2011, they were all arrested. So while our democracy is not perfect, it is doing better than ever before.

Indeed, for those who want the Supreme Court to suddenly interfere with the EC, let us flip this question on its head. Is there anyone who wants the EC to start working more like the judiciary? Our elections are easily the biggest in the world. Most of our large states have more voters than any major country in Europe. The EC has few permanent staff. During elections, they get temporary workers from other government departments. The EC trains them to set up and manage booths in every corner of the country. Then, it manages to count all the votes accurately in a matter of hours. Compare this to the judiciary which is sitting on over four crore pending cases.

Is it not the role of the courts to make citizens feel empowered?

In 2016, the Supreme Court framed rules for retired judges (and their surviving spouses) to hire domestic help at public expense. The reason apparently was that standing in lines to pay bills like common people would embarrass retired judicial officers. Such decisions are quite common. In 2018, the Madras High Court ordered the National Highway authorities to create separate VIP lanes for judges. Again, because waiting in line like everyone else would “embarrass” the judges.

Such a sense of entitlement grates on the psyche of an aspiring young Indian. And they groan each time sons and daughters of former judges invariably make it through the collegium system. Through a process that is kept secret, of course. Add to that the four crore pending cases, the sword of “contempt” which hangs over anyone who disagrees with the court, and you can see why people would complain.

And now we have the sorry spectacle of judges coming out to complain that folks on social media are being unfair to them. How could the judiciary feel pressured by mere words on social media, from people who have no power over anything? If that is still the case, would it not make more sense for judges to voluntarily stay away from reading what is said online?

Even if provisions for contempt of court are rarely used, it still has a chilling effect on free speech. Most people would not feel free to talk about judges the way they would talk about a politician or a bureaucrat for instance. Why is that?

In a democracy, the onus is not on the people to respect any particular institution. Rather, the onus is on every institution to earn the respect of the people. And for that, they must make their case, very humbly if I may add, before the Supreme Court of common citizens. I believe that those who wrote the Constitution would agree.

Abhishek Banerjee is an author and columnist. He tweets @AbhishBanerj. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment