views

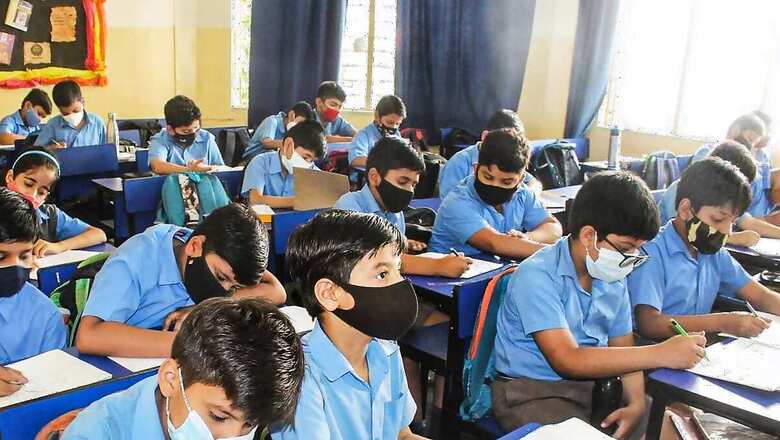

That education would be the cornerstone of India’s development was a fact that our founding fathers well-recognised. With the world’s largest population of over 1.4 billion people, this holds especially true for India. Today, 75 years after Independence, India’s progress and transformation still depend on the strength and effectiveness of our education sector. Not only employment, individual empowerment, economic growth, but social mobility and nation-building are driven by how well we perform in education.

If so, where did we go wrong? In a series of articles, the latest of which was published here (https://www.news18.com/opinion/off-centre-how-education-spending-in-india-is-much-more-than-we-think-7331035.html) I showed how our expenditure was too complicated to easily audit because it was differentially divided across many ministries at the centre and across the states and union territories. In addition, the picture of how much money is actually being spent on education is quite distorted. For example, the total amount spent by all the other ministries put together far exceeds that of the Ministry of Education by about 150 percent.

If we return to the report on Budgeted Expenditure on Education the figures for total expenditure for 2019-2020 on education is a staggering Rs 8,93,186 crores or 8.93 lakh crore (source: Analysis of Budgeted Expenditure on Education, 2017-18 to 2019-20: p.30). Of this, the Centre’s share is Rs 2,27,080 crores or Rs 2.27 lakh crore and that of the other states Rs 6,66,105 crores or Rs 6.66 lakh crore. The figures for the current year are not available, but by estimating an increase of about 22 percent as previously explained, the amount is in the realm of a colossal Rs 12 lakh crore or about $150 billion.

If we consider India’s GDP to be $3.3 trillion, then the total state spending on education is about 4.5 percent. This figure also matches World Bank estimates. If so, what is puzzling is why we are repeatedly told that Indian education spending is stuck at about 3 percent of the GDP. Consider a two-part complaint put out by Centre for Policy Research (CPR), Delhi, in May 2022 by Mridusmita Bordoloi and Sharad Pandey. Tellingly titled “A Missed Milestone: How India has been Unable to Boost Public Education Spending to 6 percent of GDP”. The authors start by stating how the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, once again, reiterates the objective of raising government spending on the education sector to 6 percent of the GDP.

No surprises here because this 6 percent goal was set way back by the Education Commission of 1964-66, better known as the Kothari Commission. The Commission clearly advocated that “if education is to develop adequately, the proportion of Gross National Product (GNP) allocated to education will rise … to 6.0 percent in 1985-86.” The National Policy on Education (1968) also accepted this figure. Skipping four decades to the UPA government led by Manmohan Singh, its common minimum programme also promised in 2004 to increase government spending on education to 6 percent of the GDP.

The said document, in addition, also contained pious platitudes about why the country’s greatest resource were its people: “India’s greatest resource is its people. The full potential of our human resources has yet to be effectively utilised. High priority will, therefore, be accorded to education. The Government will aim to increase public education spending to reach at least 6 percent of GDP, with half the amount earmarked for primary and secondary education”.

The NEP 2020 continues with the 6 percent pledge: “The Policy commits to significantly raising educational investment, as there is no better investment towards a society’s future than the high-quality education of our young people. Unfortunately, public expenditure on education in India has not come close to the recommended level of 6 percent of GDP, as envisaged by the 1968 Policy, reiterated in the Policy of 1986, and which was further reaffirmed in the 1992 review of the Policy” (26.1).

In the following paragraph (26.2), it continues: “The Centre and the States will work together to increase the public investment in the Education sector to reach 6 percent of GDP at the earliest. This is considered extremely critical for achieving the high-quality and equitable public education system that is truly needed for India’s future economic, social, cultural, intellectual, and technological progress and growth” (Ibid). “However,” Bordoloi and Pandey assert, citing this same document, “in 2021-22, the budgetary allocation for education spending, by the Union government and the states combined, was far less at 3.1 percent of the country’s GDP.”

Where and how they got this figure is far from clear because it is not referenced. I had spoken in the last column on the difficulty of obtaining reliable figures in one place. But then education minister, Prakash Javadekar, delivering the convocation address of the DY Patil University in Navi Mumbai in March 2019 already announced that government spending on education had gone up “from 3.8 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2014 to 4.6 percent during the NDA rule”. The CPR authors do not seem to have tried to trace the source of these figures, even if to challenge or differ from them.

How is it that quoting exactly these portions of government documents, a “Deliberation” on the portal The Companion on February 7, 2023, soon after the budget, fails to cite some crucial data also from the NEP 2020? “The Indian Education System and the “6 percent” Saga” by Sadath Hussain continues in the same vein as earlier laments: “Though UPA-1, 2004 ambitiously pledged to spend 6 percent of public spending on education, even 3.5 percent of GDP was not crossed even if one combined the spending of both the state governments and the central government. During 2004-05, the public expenditure on education was 3 percent of GDP and increased it to 3.4 percent of GDP during 2008-09. During 2009-10 education expenditure further came down to 3 percent of GDP. During the early period of NDA, the education expenditure was at 3.1 percent in 2014-15 which again declined to 2.8 percent in 2015-16. Since then it has been constant between 2.8-2.9 percent from 2016-17 to 2022-23.”

One begins to sniff a clear pattern of sledging and slanting in these seemingly objective assessments. This is the kind of confirmation bias that the concluding part of this series will attempt to expose.

The writer is an author, columnist, and professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Views expressed are personal.

Comments

0 comment