views

True horror has never been about a family moving into an old house and discovering a supernatural presence. It hasn’t been about possession, or for that matter, a man in a hockey mask hacking away at barely clad teens with a machete. No, I find that true horror has always carried with it political context, a tie to certain events and atrocities in history, which makes it undeniable. In that sense one could call something like ‘Schindler’s List’ or ‘Night and Fog’ horror, true horror. The film I talk about here, however, has a little more to do with the supernatural. It is an allegory, of course, but executed masterfully, rendering it timeless.

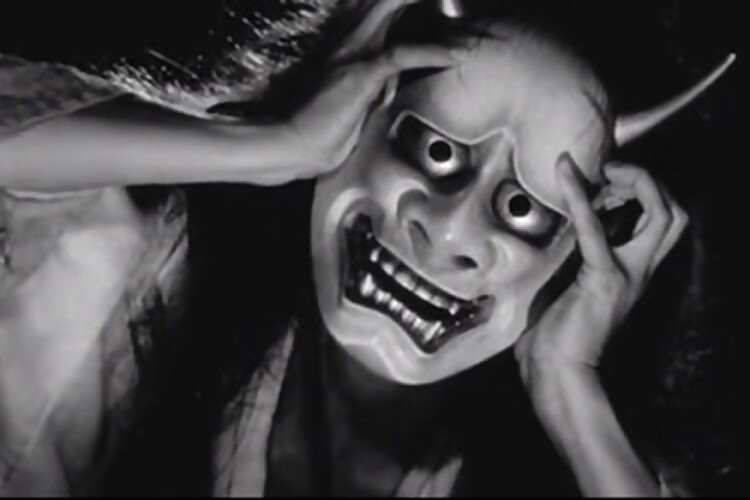

‘Onibaba’ has a dark premise. Two women, an old mother and her daughter in law, they live in a swamp. The war is petering out, and as unsuspecting samurais flee the war, somehow making their way into said swamp, the two women butcher them and sell their weapons and armor for meager amounts of food. Something happens soon—a deserter arrives, a man, someone they knew, and the younger woman begins a fierce affair. The mother disapproves, and after trying everything else in her desperation, dons the mask of a dead samurai at night, the face of a demon, to stop her daughter in law from sinning.

This is a cult worthy tale, one of jealousy, survival, and repressed sexualities; elements that are dealt with in every single frame, every single sound. The exposition is stunning—the swamp has been chosen well, and it is depicted with an eeriness inexplicable—there is tall, tall grass, and the camera chronicles its movement throughout the film. The way the wind catches it, the way it swishes and recoils and swings, there’s something distinctly sinister about it. It resembles hair, it resembles long, uncanny fingers, it resembles whatever you’re looking for in that field of grass, whatever that lurks beneath, a deep sense of odd, your very own personal brand of fear.

The cinematography is superb, complimented by the dry, moody lighting; the film-maker reveals precisely what he wants to and nothing more. The light and the shadows are his allies, bending unrelentingly to his will, and what you see in the film—the horror, the sex, the depravity of the human psyche as it heads lower and lower, towards darkness—it is raw, uncut, not tampered with. The performances compliment this. The sweat, the rags, the setting, the smoke, the night, the tall, tall grass. The film itself is a build-up for the climax, an unstoppable, edge of the seat experience, starting with the first murder and working with fear and lust and anger towards the unforgettable climax, when the subdued supernatural finally rears its nightmarish head.

The sound design is equally masterful; small sounds, innocuous sounds are constantly used to build up a scene towards its end. Think about the first sequence of 'Inglorious Bastards', a bible worthy build-up example, and consider making it more subtle. The viewer experiences angst, a nail biting angst; the viewer is slowly leaving the back rest, leaning forward towards the screen without knowing why. Sometimes it’s simply the sound of a pair of crickets, getting faster and faster as the dialogue progresses. Other times, it’s the sound of reeds breaking, snapping softly yet with an audible crunch, repeating itself over and over and over until the viewer cannot take it anymore. ‘For God’s sake, get it over with already!’ I whisper to myself. Often.

A noteworthy element of the film only reveals itself on closer inspection, when you realize that ‘Onibaba’ was made in 1964. That’s over fifty years ago. When one tries to watch contemporary horror, especially Hollywood horror, one does notice the reliance on special effects. Films like ‘Crimson Peak’ or ‘Mama’ have certain moments that will chill you to the bone, yet there’s a carefully manufactured CG spectacle involved somewhere. Now, there’s nothing wrong with that, with evolving with the times and being able to justify the use of CG in a groundbreaking manner (and there are films that have done completely without, like the immortal ‘The Blair Witch Project’, another bible)but all the same, it makes us look at Onibaba in a new light.

There’s no CG here, there’s no computer generated magic, nothing to make the vision of the film-maker a wee little bit easier, but he delivers. He doesn’t have to resort to jump scares or sudden shocks either—the slow, creeping dread the film unleashes on the viewer is entirely inescapable. The political backbone is what powers the film beyond mere horror—the film is essentially about the Hibakusha, the atomic bomb survivor, about war and the dregs it leaves behind.

Some comparisons are beautifully put—the hole is a prominent protagonist, the hole in the swamp where the two women drop the bodies involved, an undeniable comparison to the Hiroshima and Nagasaki craters. The film stays about the two women, and it is always about them. The men in the film feel like aliens, distant and simple about their wants, their ends. These two women, lying together and killing together, explore a far more vast spectrum of acknowledgements and betrayals. And like war, the film leaves its own brand of scars, and it shall linger in the viewer’s mind for much longer than one realizes.

There is more, much more, but it lies behind the 'Noh' mask of a dead samurai, behind the mask of the 'Onibaba', and I leave it there for you to discover. I would not reveal it myself. If you have not seen the film, watch it, take the mask off, and revel in discovery and horror.

Comments

0 comment