views

X

Research source

Depression can be very difficult to deal with, especially if you feel alone and isolated. Getting social support is not only desirable but it can have a real impact on your recovery process.[2]

X

Trustworthy Source

PubMed Central

Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health

Go to source

Talking to close friends is one way to get some of the support you want and need, although it's not always easy to take that first step and open up to someone about your depression. Fortunately, there are several concrete things you can do to prepare for your conversation and get the most out of it.

Preparing for Your Conversation

Accept that you are ready and willing to talk about it. This is a big piece of news you are about to share and it's okay and perfectly normal to feel nervous. Depression is considered a mental illness, and because there are a lot of misconceptions about individuals struggling with mental disorders like depression, people can sometimes feel stigmatized with their new diagnosis. However, realize that opening up about your illness is one of the steps to effective coping and recovery.

Consider who to tell. Many people don't just have one best friend but instead, have a bunch of really close or even "best" friends. You need to think about who you are sharing the information with and whether this is good for you. If you are already in counseling, explore this topic of sharing your depression with a friend with your counselor, therapist, or psychiatrist. If your friend is a great listener, discreet, trustworthy, reliable, non-judgmental, supportive and mentally healthy, then this friend sounds like the ideal person to share your concerns with. Your friend can be a sounding board for you and help you maintain a healthy perspective as you work through your recovery.

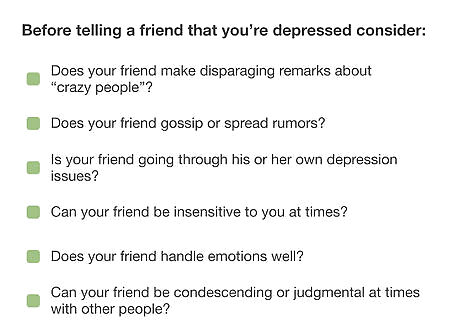

Pause and think if you're unsure about telling your best friend. If you're questioning whether or not you should tell your friend about your depression, consider how you'd respond to the following questions: Does your friend make disparaging remarks about “crazy people”? Can your friend be condescending or judgmental at times with other people? Is your friend going through his or her own depression issues? Can your friend be insensitive to you at times? Does your friend handle emotions well? Does your friend gossip or spread rumors? If you answered yes to any of these or recall any instances where your friend exhibited disconcerting attitudes and behaviors, it might be best that you just simply let your friend know that you are going through some major issues, but that you’re working on them, getting help and will be in touch. That said, sometimes friends can surprise us. If your friend is able to drop her usual behaviors or attitudes out of concern for you, and if you feel comfortable sharing this information, you can start with small pieces of information to share and see how well your friend receives it. Back off whenever you feel uncomfortable or upset.

Think about what information you want to give your friend. How much are you going to share? Sharing your condition is up to you, irrespective of whether or not you have received an official diagnosis. Start with what you think your friend will need to know both about depression in general and about your specific experience of it. What about depression is important for your friend to know? What misconceptions or myths might be important to correct? What about your personal experience is important for your friend to know? Keep in mind that your friend may have someone in her family who is depressed and may know a lot about the illness. On the other hand, your friend may know very little about depression. It is important to read up on depression and educate yourself about your illness so that you can help your friend better understand depression, how it affects you, and how they can help and support you going forward. In addition, educating yourself about depression has its own benefits for your recovery process! Remember that you do not have to explain why you're depressed. You don't need to provide a justifiable reason to be depressed or to feel sad. All you need to do to share your feelings with your best friend is to tell honestly them how you’re feeling, and ask for what you need from them, be it support, patience, understanding, or space.

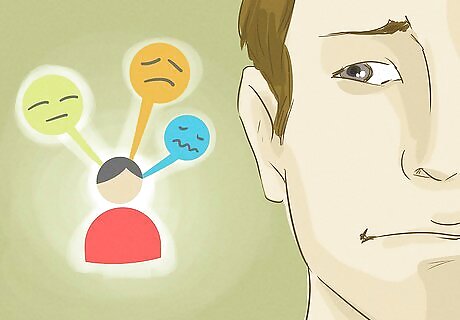

Imagine your friend's possible reactions. While you may not be able to predict how they're going to respond, weighing different possibilities might help you prepare. Be sure as well to think about how different reactions might make you feel and how you might respond. Planning in advance for this helps make sure you're not caught off-guard and that you keep your goals for the conversation in sight. Keep in mind that your friend may not understand you. People who have never suffered from depression may not be familiar with the symptoms. This means that sometimes they have a hard time understanding why you can’t “just stop feeling sad” or “just get out of bed.” This isn’t necessarily a lack of empathy or compassion on the part of your friend. Instead, it could be the case that this person cares about you and wants you to feel better, but doesn’t understand how the disorder makes people feel. Another possibility is that your friend may feel like it’s her responsibility to “fix” you. Your friend might think that they can help "lift" you out of your depression. This is not their job, as it puts pressure on both her and you. Another possible reaction is to abruptly change the subject or turn the focus of the conversation around onto herself. This possible outcome can feel hurtful, like your friend is being selfish or doesn’t care about you, but it is more likely the case that they simply don’t know how to respond to what you’ve said, or that they are trying to show you that they’ve been in a similar situation and can relate to what you’re feeling. In each of these scenarios, prepare what you will do and say. For example, if your friend seems to be reacting to your disclosure by using language that implies they want to "fix" you, point out that it's not your friend’s job to fix you (since you're not "broken") and that what you would like instead is support. If she has a hard time accepting this, plan to say something like "I have to be able to sort this out on my own. Your support means the world to me, but you can’t do this for me, even though I know you wish you could. It’s like wanting to help me for a test, but then doing all the studying for me. If I don’t have the knowledge to take the test, I can’t pass it myself. This is very similar.”

Decide what information or response you want in return. To have a conversation that both speakers can feel good about at the end, they have to be working towards building the “common ground,” or the common knowledge between them. Think about what you want out of the conversation and how you want your friend to respond. In all likelihood, your friend will want to help you, so plan ways to let your friend know how to do so in the best way possible. For example, do you need your friend to “just” listen and be someone you can talk to? Do you need to ask for help with getting to and from treatment? Do you need someone to help you manage everyday tasks, like cooking, cleaning, and laundry? Know that your friend might only be able to help you out in small ways, so it’s best to go into the conversation a clear sense of what you want from a friend. You could also wait for your friend to ask if and how she could help you, and then discuss whether or not your friend could contribute in the way you need her to. For instance, you could ask your friend to speak with you for a few minutes every night to help you with your insomnia (a symptom of depression), check in with you to see how your day went, or to check to see if you took your medication that day.

Write down what you want to say. Taking notes can help you gather your thoughts and organize them. Once you've written it down, practice saying it out loud in front of a mirror.

Practice the conversation. Ask a someone you trust who is already informed about your situation, such as a parent or therapist, to practice the conversation with you. Role-playing the conversation can help you prepare. In the role-play, you'll act out potential scenarios; you will be yourself in the role-play, and your partner will play the role of your friend. React to whatever the other person says, even if you think it is ridiculous or unlikely to happen. Just practicing responding to absurd or surprising statements from a friend can give you the confidence to approach a difficult conversation like this one. To get the most out of the role-play, be as realistic as possible in your responses. Incorporate non-verbal communication into your role-play. Remember that gestures, posture, and tone of voice are a major factor in your conversation. After the role-play, ask your partner for feedback, telling you what worked well and some areas where you might think more about what you will say or otherwise improve your response.

Communicating with Your Friend

Plan a casual activity with your friend. You can take her to lunch, or go for a walk somewhere you both enjoy. Research has shown that mildly depressed people’s moods improve when a task diverts attention to something external such as an activity. Being in a better mood can make it easier for you to be able to open up and talk about your feelings. If you're not in the mood to do an activity, don’t feel pressured to plan one. A conversation over a cup of tea at the kitchen table or on the couch can suffice.

Ease into talking about your depression whenever it feels right. The best way to start is to tell her that you have something important you want to share, so she knows not to take your conversation lightly. If you don't know how to bring it up or feel uncomfortable, try saying something like, "Hey, I’ve been feeling kind of weird/down/upset lately. Do you think we could talk about it?" Make it clear from the beginning of the conversation whether you want her to listen and hear what you have to say, or want her opinion or suggestions.

Communicate to your friend whether the information is confidential. Be sure to let your friend know whether what you're telling them is private or if they are permitted to communicate your difficulties to other people on your behalf.

Say what you have practiced. Be as specific and direct as possible. Don't dance around what you need or what you're requesting. It's okay if you get a little tongue-tied and shaky as you talk. Just talking is the hardest part! If you’re having a hard time dealing with your emotions during the actual conversation, it’s okay to admit this to your friend. Letting them know how hard the conversation is for you might even be helpful to your friend to understand your state of mind and how serious the situation is. If you begin to feel overwhelmed at any point during the conversation, it’s okay to take a break, take a deep breath and gather your thoughts.

Help your friend feel comfortable. If your friend seems uneasy, break the tension by thanking her for being there and listening, or apologizing for taking up her time or having a hard time talking about it (if that is true). Individuals with depression are sometimes prone to feeling guilty. Guilt can be persistent, but it can also be managed and minimized. If you feel guilty during your conversation, one useful way to manage this perceived guilt is to remember that guilty thoughts are not facts. You are not burdening your friend by sharing your feelings. Your friend is more likely to feel grateful that you trusted her with this information and eager to help your recovery than she is to feel the "burden" you envision.

Keep your friend engaged. For your conversation to work, your friend needs to be listening to you completely. There are many ways to hold her attention, including making eye contact, using gesturing and body language (e.g., facing the person, not having your arms or legs crossed), speaking clearly, and avoiding outside distractions (e.g., background noise, people passing, cell phones ringing). Look for signs of active listening. When a person is listening closely, they are deeply focused, trying to understand what you're saying. Check for cues like eye contact, nodding, or meaningful responses to what you're saying (even "uh-huh" can be meaningful!). People also show that they understand a conversation with their contributions to that conversation. They might repeat or paraphrase what was said, ask follow-up questions, and otherwise be working to keep the conversation going. When people stop understanding or are at a loss for words, they may use filler words. Filler words are “go to” words and can vary from person to person. They may use the same phrases over and over again (e.g., “that is interesting”). They may also trail off (i.e., not finish sentences) or not be working to keep the conversation going. Be aware, however, that these responses can vary from person to person. For example, some people think more clearly when they aren't making eye contact and may deliberately avoid it in order to concentrate on what you are saying. Think about how your friend talks and how she acts when she's paying attention.

Bring resolution to the conversation by deciding on a "next step." When a person (like your friend) wants to help, she wants to know what actions she can take. This is part of human psychology: we feel good when we do something for others. Helpful actions can also alleviate some of the guilt your friend might feel when she sees you in distress. You should talk about your feelings as much as you need to, but it helps to end the conversation with something concrete or specific your friend can help you with (such as letting you vent about your feelings for half an hour or taking you out to get your mind off your problems). Recall what you had decided to request or hope for when you were preparing for this conversation and tell your friend about that.

Transition out of the conversation. Pay attention to your friend and how the conversation is going. When you feel it's time to move on, suggest a different topic or move to end the conversation by saying something like, “We should be getting home,” or, “I’ll let you go, I don’t want to take up too much of your time.” This move is mostly likely up to you, as your friend may feel uncomfortable ending the conversation.

Dealing with Your Friend's Response

Don’t forget about your best friend’s feelings. Although this conversation should be about you, don’t forget your friend will have feelings and they may not always be as you expect (you may want to address this in role-playing as described above).

Be ready for potential negative reactions. Your friend may cry or get angry. This is a common response when one is the recipient of another person's upsetting or difficult news. Remember this is a natural response and does not mean you've done anything wrong! This might be a good time to assure your friend that you don't expect them to have all the answers, and that you just need them to listen and be there for you. Don't take anger or crying as a sign of rejection. You can try talking to your friend again another time. Meanwhile, find someone else close to you that you can talk with.

Change tactics if you feel like the conversation is going in a bad direction. If you're having trouble communicating with your friend or she has an extreme reaction, try the following 4 steps, which are helpful in mediating difficult conversations. Inquiry: Ask and make an observation. You could say, “Have I upset you with this topic? I would like to listen to how you feel.” Acknowledgment: Summarize what your friend stated. You can really further the conversation along if you can help your friend calm down. Summarizing what your friend said will help your friend feel like someone is listening. Advocacy: Once you comprehend your friend’s point of view, you are getting close to coming to a mutual understanding. You can take this opportunity to clarify what you’ve learned about depression, or to share with your friend what is appropriate for your friend to do or not do, such as, “Don’t worry. My depression doesn’t have anything to do with how good of a friend you are. You are my best friend, and one of the few reasons I smile these days.” Problem-solving: By this time, your friend hopefully would have calmed down so you can fulfill your objective. Finish stating what you wanted to state. Have your friend help you find a therapist, help you make therapy appointments, or just to be there to listen to you. If these 4 steps don't work, it may be best to draw the conversation to a close. Your friend may need time to take in the information.

Expect that your friend might disclose information about herself in turn. Describing a similar personal experience is their way of showing they understand or can relate to your experience. Depending on the magnitude of this information, this could take your conversation in a whole new direction. If that happens, attend to your friend, but also make sure to bring resolution to your own situation at some point.

Know that your friend may “normalize” your situation. Normalizing is when a person attempts to help by trying to make you feel “normal” (e.g., saying, “Everyone I know is depressed”). Don't take this as a rejection of your problem. Self-disclosure and normalizing are actually good signs, because they mean your friend is trying to connect with you and/or show that you are being accepted. However, don't let your friend's "normalization" tactic prevent you from saying what you need to say! At the moment, it isn't important how many depressed people your friend knows. What is important is that you tell your friend about your OWN feelings and experience. Follow the conversation through to the end.

Debrief with someone else. No matter how well (or badly) things go, it can be helpful to talk about the conversation with someone you trust once you've finally talked to your best friend. People that can help include your therapist or counselor, another close friend, or your parents. They can provide an objective opinion about the conversation and help you process your friend’s responses.

Comments

0 comment