views

Looking for Signs

Realize there is no "one way" to be autistic. Autism is called a spectrum disorder because every autistic person is different, and some of them function better in certain areas than others. Some autistic people communicate nonverbally, while others are extremely good with verbal communication and may have a large vocabulary for their age. Some really struggle with executive dysfunction, while others have minimal issues transitioning from activity to activity and taking care of themselves. There are many "ways" to be autistic, and just as no non-autistic person is the same, no autistic person is the same, either. Watch out for using "subgroups" as well, such as describing someone as "high-functioning" or "low-functioning". Since everyone has their strengths and weaknesses, using these terms doesn't adequately describe an autistic person's experiences or strengths.

Analyze their childhood behaviors. Oftentimes, if a teenager is diagnosed with autism, it's because their behaviors weren't pervasive enough to significantly interfere with their development - for example, they're probably not going to communicate entirely non-verbally. However, some of the signs may actually become more obvious when the child reaches adolescence, such as trouble with social abilities. If you know anything about the teen's past, try looking back and seeing if you can recognize any of these signs from their early childhood. Did they learn to speak later than most children (for example, not saying two or three word sentences before the age of four)? Regardless of when they began speaking, did they exhibit unusual speech patterns, such as echolalia? Did they learn certain skills before most children would (such as reading at age two)? Did they have trouble dealing with transitions from one event to another, even if the transition seemed simple? For example, a simple "Come on, let's get in the car and go to Grandma's" could have spurned what seemed like a temper tantrum. Did they stim? While stimming isn't limited to autistic children, it's much more prevalent than in non-autistic children. Keep in mind that some autistic children may have been forced to stop stimming by non-autistic individuals; try to recall if they've ever started to stim, but then stopped. Did they play differently than other children would play? For example, an autistic teen may have not engaged in "playing pretend" as a child, or would have engaged in unusual play, such as feeling a doll's hair or stacking Lego bricks rather than using these toys in the way that one would expect them to be used.

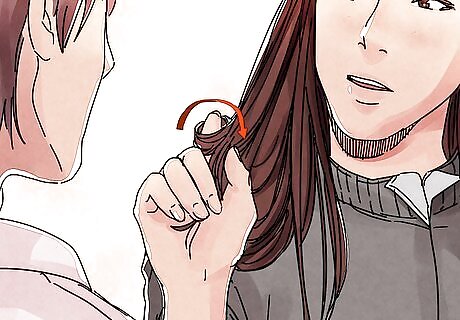

Look for signs that may have carried on from childhood. Certain traits of autism can remain for quite a long time if the autistic teen has never received any form of treatment for it. These can be things that you might see in any child, such as stuttering or stammering, or something more significant, such as constant avoidance of eye contact. Consider the following questions when looking for signs that this teen may be autistic. Do they have special interests that they research constantly? Sometimes these special interests can be people, so they can become obsessed with a person to nearly stalker-like levels - whether the person is a celebrity or someone they know in person. Do they experience meltdowns (when they lose control over their emotions, scream, and in some cases, exhibit destructive behavior) or shutdowns (when they become more passive, retreat "into" themselves, and sometimes lose certain abilities, such as speaking)? Meltdowns may look like tantrums, especially in children, but a meltdown or shutdown is often a response to sensory overload or a sudden change in routine. Do they stim in not-so-obvious manners? This can be easy to overlook, as some stims may look like typical fidgeting that you'd see in just about any teenager. However, try to watch more closely and see how often they perform these behaviors. Do they tap their pencil or play with their hair frequently, for example? Do they stick to strict routines and get upset when the routine is altered in some way? For example, if an autistic teen is told, "You're not going to school today", they may become distressed and complain, even if they dislike school. Do they have sensory problems - for example, do they cover their ears and get visibly upset by loud noises, or have strange eating patterns, such as either eating bland food or overly spicy food? Some teens are hypersensitive to stimulation, while others are hyposensitive to it. Some teens may even have a mix of both.

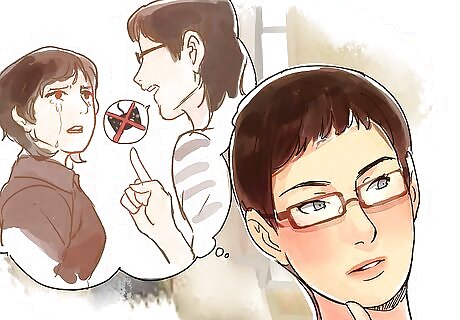

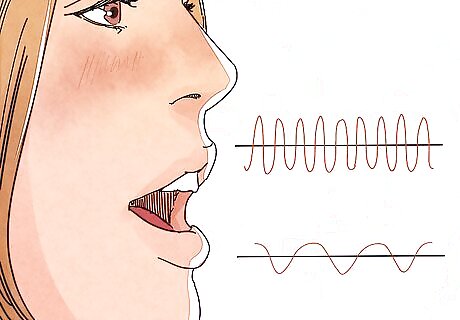

Analyze long-lasting challenges and unusual aspects of the teen's social skills. Some teenagers may just be socially awkward and not have many friends. However, autism is much more than just "social awkwardness" - it involves some more serious problems with social skills than just teenage social problems. Search for trouble in the teen's social life and see if any of the following apply. Do they either make too much or too little eye contact? Infrequent eye contact is most commonly associated with autism, but some autistic people are considered "starers", and may rarely break eye contact. Do they have trouble understanding figurative language or sarcasm? For example, if an autistic teen is told, "Go jump in a lake!", their response might be, "Why? I can't swim" or "What lake? There's no lake here". Do they go on long-winded talks with barely a break to let the listener say something? These "rambles" or "infodumps" can be about anything, but you may hear about the autistic person's interests. Do they have few or no real friends? This may not apply in particularly accepting environments, but autistic teens may not realize that a fair-weather friend is not a real friend, even when the so-called friend tries to hint at this. Are they often a target for bullying or manipulation, and never seem to realize what's going on until it's too late? Some autistic people are extremely loyal, so you may also see them sticking with a "friend" who belittles them and treats them terribly. Are they most often alone? (This may be mistaken for being an introvert. Keep in mind that autistic people can be introverts, but they can also be extroverts or ambiverts.) Do they communicate in seemingly odd ways, such as speaking in a monotone or using very few gestures?

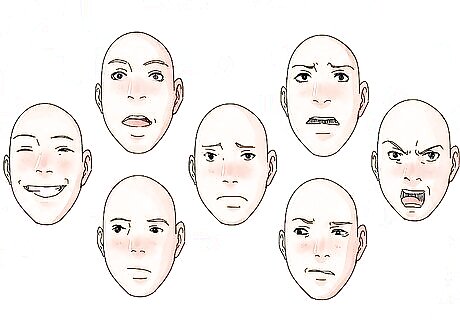

Watch for signs of alexithymia in the teen. Alexithymia is difficulty identifying and describing one's emotions. Autistic people can struggle with alexithymia, so if they're dealing with some sort of emotion, they may not recognize that they're feeling this emotion until it starts showing up in physical symptoms (e.g. sore throats, headaches). They may also have trouble identifying the emotions of others, and have a somewhat decreased empathy response, although it's important to understand that autistic people are capable of feeling empathy regardless of alexithymia. While alexithymia isn't directly related to autism, it can be a sign of it.

Arrange for an autism assessment. At an appointment with your teen's doctor, explain that you suspect your teen to be autistic - or if your teen also suspects that they are autistic, allow them to communicate that if they so wish. You should be referred to someone who can assess your teen for autism. Don't ask for an assessment in front of your teen without your teen knowing that you're going to ask. This may shock and upset your teen, especially since you didn't keep them in the loop. Be aware that teenage girls may be at a higher risk of misdiagnosis. There are quite a few stories of autistic girls and women getting misdiagnosed for many reasons - whether it was because the doctor didn't believe a woman could be autistic, or because they identified comorbid conditions instead of autism signs. Some doctors or psychologists may diagnose an autistic girl with depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, OCD, or any other psychological disorder that can account for some of their behaviors, but not the autism behaviors. Try to make sure that an autism assessment is in the picture, even if the doctor argues.

Keep an eye out for comorbid conditions. An autistic teen may have some comorbid conditions along with their autism. (However, keep in mind that if a teen was diagnosed with one of these initially, and then was later diagnosed with autism, that doesn't mean they have the comorbid condition.) Some conditions that occur more frequently in autistic people are: Depression ADHD Anxiety or OCD Sensory Processing Disorder (also known as Sensory Integration Disorder) Developmental coordination disorder Bipolar disorder Some autistic teenagers may have seizures. They may have epilepsy as well as autism, but some autistic people who are going through puberty and adolescence can experience seizures without having epilepsy.

Helping and Supporting

Presume competence. If your teen has been diagnosed as autistic, you may feel inclined to help them with everything. Don't. Autistic people are not incapable of taking care of themselves just because they're autistic. Every autistic person struggles with some things, but not with others. Ask your teen what they need help with, and help them only with what they tell you they need help with. If your teen doesn't say they need help with social situations and you jump in anyway, all you're going to do is aggravate them. Autistic people are not "high-functioning" or "low-functioning", and this label is hated by many autistic people. An autistic teen considered "low-functioning" because of his severe sensory problems and nonverbal communication may have incredible reading comprehension skills and be writing long novels. Another autistic teen considered "high-functioning" might have great social and communication skills, but have severe executive dysfunction, pull out her hair, and can't drive because she's hyposensitive and may miss important road signs or stoplights. Autistic people all have their own personal strengths and weaknesses, and it's impossible to define these by a functioning label.

Use identity-first language. Autism is part of a person's identity, and while it might be more inclining to say "person with autism" to be considered politically correct, this removes part of the autistic person's identity. Autistic people are autistic their whole lives, and saying "person with autism" makes it seem as though that person's autism isn't a part of them and it can just be "removed". Keep in mind that sometimes, this is a matter of personal preference. Some autistic people prefer to be referred to as a "person with autism", but if they haven't specified if they like this or not, stay on the safe side and refer to them as an autistic person.

Request an IEP for your teen. Parents can request an IEP for their teen, but the teen will have to be assessed to determine whether or not they qualify for an IEP. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, also known as IDEA, autistic children and teens are eligible for IEP services. An IEP can allow your teen some extra services - for example, permission to bring in stim toys, exercise balls to sit on, permission to leave the room if they're feeling overwhelmed, speech therapy, and more. Having an IEP in place can help your teen's teachers better understand how to support them in the classroom. Let your teen participate in the IEP meetings and communicate their needs. At high school age, autistic teens are not children and their parents should not be making the decisions for them. Make sure your teen gets some input on the services they're getting, even if it's just continuously asking, "Does that sound to you like it would help you?" Teachers can suggest to the parents of a teen that they request an IEP, but they do not have the power to call in an IEP request for the student without permission from the parents. You may want to discuss setting up a quiet spot for your teen at the school. If your teen is prone to meltdowns or shutdowns, especially at school, a prime point of the first IEP meeting should be finding a quiet place for them to calm down.

Try therapies for issues such as speech or motor problems. Some autistic teens have problems with their verbal communication, and speech therapy may benefit them greatly. Others have trouble with motor skills, and may need therapy for either gross motor skills or fine motor skills. Additionally, there are some sensory integration therapies that your teen can use to learn to cope with sensory problems. Try looking into these therapies and reviewing any potential therapists thoroughly. Be wary of ABA therapies. ABA therapy, also known as Applied Behavior Analysis, can work for some autistic teens who have trouble with motor skills, if the therapist is a good fit. However, there are also many, many stories of autistic people being abused in ABA therapy, and leaving the therapy with PTSD. Be extremely careful if you start looking into ABA therapies, and if your autistic teen starts becoming distressed with the therapy, don't force them to go.

Search for ways to make communication easier. Some autistic people are primarily nonverbal communicators, and others may lose the ability to communicate verbally when having a shutdown. While many teens that receive a late diagnosis of autism may communicate verbally, some of them may prefer nonverbal communication; work with them to find ways to communicate their needs. If the teen communicates primarily verbally, and only has infrequent cases of communicating nonverbally (for example, during shutdowns), it may be possible to figure out what stims show the teen's needs. For example, wringing their hands could mean, "It's too overstimulating and I need to leave". Consider sign language if the teen is primarily nonverbal, but doesn't have significant trouble with coordination and eye contact. How to Choose AAC for an Autistic Person may be a good article to look at if your teen has severe trouble with verbal communication or communicates (or prefers to communicate) nonverbally.

Assist the teen in finding ways of stimming if they want help. While this may seem confusing at first, there are actually many ways you can help an autistic teen find new ways of stimming. For example, you could help them find or make stim toys, or help them to redirect stims that they may not realize are disruptive. For example: "I've noticed you've been repeating phrases to yourself during tests. Do you think you could try playing with your ring or chewing on your necklace instead? Talking during tests can make it harder for the other students to focus, even if you're just whispering." Suggest to the teen that they read How to Stim, How to Stim Discreetly, and How to Replace Harmful Stims to help themselves with stimming. Do not try to stop the teen from stimming entirely. Stimming helps autistic people to focus and decrease sensory overload, and preventing them from stimming can cause them difficulty in focus and well-being - and forcing them to stop stimming by restraining them can lead to lifelong problems. It's okay to help them change harmful stims to non-harmful ones or suggest quieter stims to avoid disrupting people in public, but never try to stop them from stimming at all. Similarly, don't force a teen to engage in a quieter stim just because you don't want to be embarrassed. If your teen flaps their arms when they're happy or anxious, unless there's a legitimate reason to ask them to use a quieter stim (e.g. you're at airport security and currently have to undergo additional screening), don't ask them to use a quieter stim. This stifles them and teaches them that other people's feelings are more important than their own.

Show the teen support. Never apologize for them simply being autistic, or feel sad that they're autistic; autistic teens are capable of understanding you and being quite successful, even if they are nonverbal or struggle with executive dysfunction. Being autistic is not a curse, and right now, especially at this point in their life, an autistic teen will need your support and care more than ever. Show them support by caring for them unconditionally and not supporting organizations against autism (such as Autism Speaks). Instead, find organizations that support and are run by autistic individuals. Experience autistic culture with them. Autistic people have accomplished many things, with one example being writing books or blogs. Look at groups that don't demonize autism, such as the Autism Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN). These groups are run by autistic people. Support them during Autism Awareness Month. Autism Awareness Month, which takes place every April, can be very difficult for autistic people. Support Autism Acceptance Month instead. As a general rule, try to avoid organizations that use a puzzle piece for their logo. Autistic people are already complete; there is no missing piece from them. The puzzle piece is also often associated with Autism Speaks, which is often considered by autistic people to be a hate group disguised as an organization. Regardless of whether you and your teen actively support autism organizations, make sure they understand that you love them unconditionally - autism and all.

Comments

0 comment