views

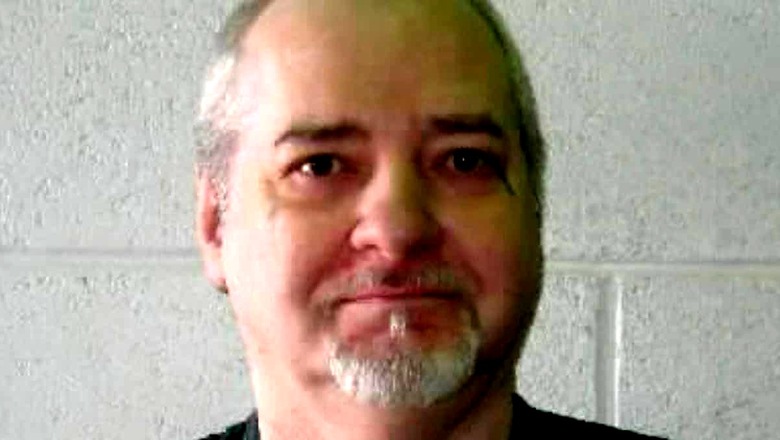

The US state of Idaho halted the execution of serial killer Thomas Eugene Creech on Wednesday after medical team members repeatedly failed to find a vein where they could establish an intravenous line to carry out the lethal injection.

Creech, 73, has been in prison half a century, convicted of five murders in three states and suspected of several more. He was already serving a life term when he beat a fellow inmate, 22-year-old David Dale Jensen, to death in 1981 — the crime for which he was to be executed. Creech, one of the longest-serving death row inmates in the U.S., was wheeled into the execution chamber at the Idaho Maximum Security Institution on a gurney at 10 a.m.

Three medical team members tried eight times to establish an IV, Department of Correction Director Josh Tewalt told a news conference afterward. In some cases, they couldn’t access the vein, and in others they could but had concerns about vein quality. They attempted sites in his arms, legs, hands and feet. At one point, a medical team member left to gather more supplies. The warden announced he was halting the execution at 10:58 a.m. The corrections department said its death warrant for Creech would expire, and that it was considering next steps.

While other medical procedures might allow for the execution, the state is mindful of the 8th Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, Tewalt said. Creech’s attorneys immediately filed a new motion for a stay in U.S. District Court, saying “the badly botched execution attempt” proves the department’s “inability to carry out a humane and constitutional execution.” The court granted the stay after Idaho confirmed it would not try again to execute him before the death warrant expired; the state will have to obtain another warrant if it wants to carry out the execution.

“This is what happens when unknown individuals with unknown training are assigned to carry out an execution,” the Federal Defender Services of Idaho said in a written statement. “This is precisely the kind of mishap we warned the State and the Courts could happen when attempting to execute one of the country’s oldest death-row inmates.” Six Idaho officials, including Attorney General Raul Labrador, and four news media representatives, including an Associated Press reporter, were on hand to witness the attempt — which was to be Idaho’s first execution in 12 years.

The execution team was made up entirely of volunteers, the corrections department said. Those tasked with inserting the IVs and administering the lethal drug had medical training, but their identities were kept secret. They wore white balaclava-style face coverings and navy scrub caps to conceal their faces. With each attempt to insert an IV, the medical team cleaned the skin with alcohol, injected a numbing solution, cleaned the skin again and then attempted to place the IV catheter. Each attempt took several minutes, with medical team members palpating the skin and trying to position the needles.

Creech frequently looked toward his family members and representatives, who were sitting in a separate witness room. His arms were strapped to the table, but he often extended his fingers toward them. He appeared to mouth “I love you” to someone in the room on occasion. After the execution was halted, the warden approached Creech and whispered to him for several minutes, giving his arm a squeeze. A few hours afterward, Labrador released a statement saying that “justice had been delayed again.” “Our duty is to seek justice for the many victims and their families who experienced the brutality and senselessness of his actions,” the attorney general wrote.

Creech’s attorneys filed a flurry of late appeals hoping to forestall his execution. They included claims that his clemency hearing was unfair, that it was unconstitutional to kill him because he was sentenced by a judge rather than a jury — and that the state had not provided enough information about how it obtained the lethal drug, pentobarbital, or how it was to be administered. But the courts found no grounds for leniency. Creech’s last chance — a petition to the U.S. Supreme Court — was denied a few hours before the scheduled execution Wednesday. On Tuesday night, Creech spent time with his wife and ate a last meal including fried chicken, mashed potatoes, gravy and ice cream. A group of about 15 protesters gathered outside the prison Wednesday, at one point singing “Amazing Grace.”

An Ohio native, Creech has spent most of his life behind bars in Idaho. He was acquitted of a killing in Tucson, Arizona, in 1973 — authorities nevertheless believe he did it, as he used the victim’s credit card to travel to Oregon. He was later convicted of a 1974 killing in Oregon and one in California, where he traveled after earning a weekend pass from a psychiatric hospital. Later that year, Creech was arrested in Idaho after killing John Wayne Bradford and Edward Thomas Arnold, two house painters who had picked him and his girlfriend up while they were hitchhiking. He was serving a life sentence for those murders in 1981 when he beat Jensen to death. Jensen was disabled and serving time for car theft.

Jensen’s family members described him during Creech’s clemency hearing last month as a gentle soul who loved hunting and being outdoors. Jensen’s daughter was 4 years old when he died, and she spoke about how painful it was to grow up without a father. Creech’s supporters say he is a deeply changed man. Several years ago he married the mother of a correctional officer, and former prison staffers said he was known for writing poetry and expressing gratitude for their work.

During his clemency hearing, Ada County Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Jill Longhorst did not dispute that Creech can be charming. But she said he is nevertheless a psychopath — lacking remorse and empathy. Last year, Idaho lawmakers passed a law authorizing execution by firing squad when lethal injection is not available. Prison officials have not yet written a standard operating policy for the use of firing squad, nor have they constructed a facility where a firing squad execution could occur. Both would have to happen before the state could attempt to use the new law, which would likely trigger several legal challenges.

Other states have also had trouble carrying out lethal injections. Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey paused executions for several months to conduct an internal review after officials called off the lethal injection of Kenneth Eugene Smith in November 2022 — the third time since 2018 Alabama had been unable to conduct executions due to problems with IV lines. Smith in January became the first person to be put to death using nitrogen gas. He shook and convulsed for several minutes on the death chamber gurney during the execution. Idaho does not allow execution by nitrogen hypoxia. In 2014, Oklahoma officials tried to halt a lethal injection when the prisoner, Clayton Lockett, began writhing after being declared unconscious. He died after 43 minutes; a review found his IV line came loose.

Comments

0 comment