views

The interplay between great power competition and the green energy transition has in large part brought forth the spectre of inflation. As the world steps out of the shadows of the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation risks upending the nascent economic recovery in the short term and posing structural challenges to global stability in the long term.

The Energy Crisis: How We Got Here

While demand for oil, gas and coal grew steadily over the last five years, supply from the private sector did not respond sufficiently. Globally, the fossil fuels industry has suffered from several years of underinvestment. Institutional investors, wary of the Environment and Social Governance (ESG) implications of supporting polluting businesses, preferred to deploy capital in emerging clean technologies – from wind and solar to batteries and hydrogen.

A devastating 2011 tsunami which damaged a nuclear plant in Fukushima, Japan, raised awareness regarding risks of nuclear power. The European manufacturing powerhouse, Germany, which neither sits near fault nor tidal zones, was pushed by environmentalists to phase out its atomic power plants. The EU’s heavy focus on decarbonisation also resulted in coal plants being mothballed. It simultaneously raised the contribution of renewables in the generation mix. Nuclear and coal both typically provide uninterrupted 24-hour “baseload” generation, while renewable output is heavily weather dependent. The relatively “clean” fuel on which baseload electricity supply and winter heating has become more dependent on, is gas. It is a hydrocarbon that Europe, Japan, Korea, China and India import by pipelines or Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) vessels. These large economies run an energy deficit and rely on imports from several countries including the US, Russia, Australia and Qatar. While LNG lends the global energy market some flexibility, the price of it has largely depended on where Asia, the largest consumer, is willing to pay for the cargos.

From the first half of 2021, Russia leveraged its positions as one of the world’s largest suppliers of energy. Until now, 41 per cent and 60 per cent of EU gas and coal demand respectively has been satisfied by Russian imports. Against the backdrop of an energy transition that constrains baseload generation and reduces flexibility, even small changes in supply result in major price moves. While meeting contractual obligations, Russia’s energy suppliers steadily reduced pipeline flows and coal availability. Between early 2021 and now, the European benchmark gas contract rose eleven-fold and coal prices eight-fold. The new, much-touted €9.9 billion Nord Stream 2 pipeline which connected Russia to Europe was set to bring relief to the market, but as accusations of price manipulation ratcheted up, Germany delayed its certification. Energy price inflation soared, damaging industrial competitiveness, reducing consumers’ disposable income, pressuring central banks and threatening Europe’s economic recovery.

Great Power Competition and Energy Wars

Europe’s increased dependency on gas has played a role in Russia’s geopolitical calculus. On one hand, the timing of Russia’s military operations in Ukraine cannot be seen as independent of concurrently rising inflationary pressures which risk derailing Europe’s recovery. Any coordinated military action by the West against Russia could be countered by a cessation of gas supply. This could send European inflation soaring and create mass social unrest. Germany’s Economy Minister, Robert Habeck, said on March 3, 2022, that he “wouldn’t support an embargo on imports of fossil fuels from Russia,” adding that he “would even speak out against it because we would threaten the social peace in the [German] republic with that.” Russia, therefore, has a bargaining chip.

On the other hand, weaning Europe off this dependency fits into the US’ long term strategic and commercial goals. A raft of sanctions that followed Russia’s intervention in Ukraine saw the US back the cancellation of Nord Stream 2. While this serves to partly decouple the continent from its Eurasian neighbour, the move stands to significantly benefit US gas exporters. A larger customer base for LNG opened and the equity market richly rewarded the energy majors based on future expectations.

Meanwhile, Russia has now traded windfall gains accrued from oil and gas sales – which accounted for nearly half of its total $489.8 billion in exports in 2021 – for achieving what President Putin believes are larger geopolitical objectives in his neighbourhood. But crushing sanctions and large-scale divestments by international energy majors like BP and Shell in Russian energy assets have yet to trigger a punitive response from Moscow in the context of agreed gas supply. Pipeline flows into Europe continue and contracts are being honoured.

However, on the outside chance if this were to change, Europe will scramble to fill storages this summer with LNG imports. Such action will be imperative to avoid rolling blackouts later this winter when heating demand rises and renewables output falls. In this case, importers must outbid Asia to secure supplies. This can lead to spiraling prices across the world until industries find it unprofitable to produce goods using electricity generated from such highly priced gas. Cost of finished goods will rise until demand destruction solves the equation. All together this can send the global economy into deep recession.

ALSO READ | War in Ukraine: Pax Americana Was Never Absolute, Now It Will Exist Even Less

A negative scenario of hyperinflation assumes the global energy market will be relatively free and efficient, and the international community abides by the sanctions imposed on Russia. Industrial leaders like China might circumvent sanctions and the West’s decision to delink Russia from the SWIFT payments system. Adopting CIPS – the Chinese equivalent of SWIFT – might enable China to access Russian energy at heavily discounted rates. As a result, projects like the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline might see quick progress.

Such a move might strengthen China’s international competitiveness when Europe and other US allies purchase oil and gas at elevated free market rates. This can lead to further bifurcation in the global order by accelerating both the economic rise of Russia-friendly nations and a further deindustrialisation of Europe. This would more broadly fit into the basic thrust of the Russia-China joint statement from February 4, 2022. It gave a glimpse of how the two countries envision a transformed world order. This change will in part be catalysed by China’s access to low-cost raw materials and natural resources. In many ways, this mirrors the US, which in the past built a competitive edge by securing and dominating large sections of the global fossil fuels space. It’s clear that the way countries react to Western sanctions on Russia will determine the nature of the global commodity market which in turn will influence the great power competition between Asia and the Western bloc.

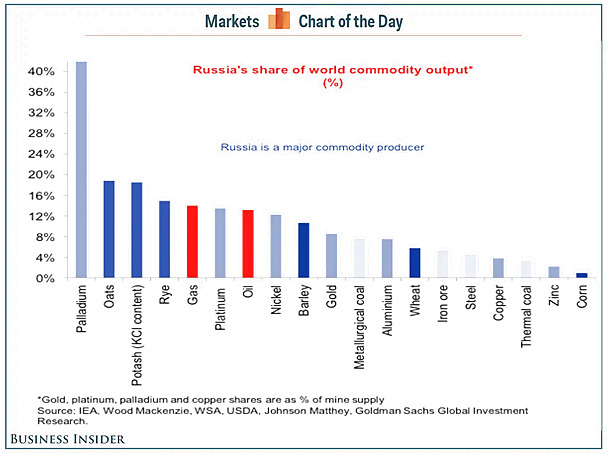

That said, developed economies are waking up to the reality that natural resource security is paramount in a fractured, multi-polar world. Russia produces 13 per cent and 14 per cent of the world’s oil and gas respectively. It is also a dominant player in range of metals and even agricultural products. Many of the metals are essential inputs in clean energy technologies including solar panels, wind turbines and batteries. The challenge of cutting Russian imports while managing inflation has led to significant policy shifts. Recently, Germany decided to extend the life of several coal and nuclear plants, award nuclear energy and gas “green” status, and commit to building new LNG terminals. US oil giants like Exxon Mobil, which have reaped profits over the last year, have signalled they may respond to elevated prices in the commodities supercycle by investing in raising output over the coming years.

While such moves are critical for ensuring long-term macro stability, they come with the risk of nations not delivering on their COP26 climate goals. But more pressing in the short term is the need to manage the relationship with Russia amidst the Ukraine crisis. Europe’s inflexible power generation stack, a tight global supply-demand balance for hydrocarbons, and a range of supply-side geopolitical risks will have to be assessed and dealt with carefully to ensure broad economic stability.

Surya Kanegaonkar is a commodities trader and columnist based in Switzerland. For over a decade, he has held key roles in the natural resources sector, working for an investment bank, miner and utility. He earned an MSc in Metals & Energy Finance from Imperial College London. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinion News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment