views

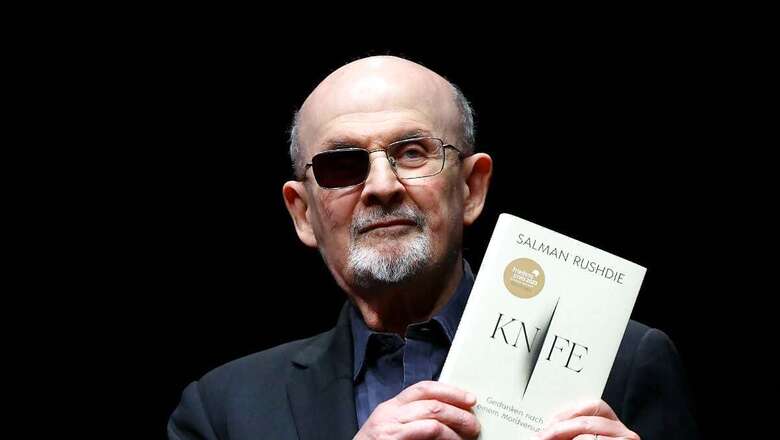

It happened out of nowhere. On August 12, 2022, when Salman Rushdie was about to give a lecture on “the creation of safe spaces in America for writers from elsewhere” and his “involvement in that project’s beginnings” in Chautauqua, New York, a ‘running man’ approached him. “Black clothes, black face mask. He was coming in hard and low: a squat missile. I got to my feet and watched him come. I didn’t try to run. I was transfixed.” The masked man stabbed him repeatedly. But, Rushdie survived to tell his story. Some would say it is a miracle of destiny.

Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder is the work of a writer who has defeated death. Rushdie refers to the attacker as “the A” ((My Assailant, my would-be Assassin, the Asinine man). The stabbing caused near-fatal wounds and the permanent loss of his right eye. “My bulging boiled-egg eye hung out of my face…,” he writes, an unforgettable description of arguably the most disturbing consequence of the attack. He seesawed between life and death, enduring unbearable physical pain, but triumphed in the long run with courage, determination — and good luck.

Memories of the unsettling phase before his eventual recovery create the essence of Knife, an important work by a great writer who has had to pay for being who he is: a man who has dared to use his right to free speech. In Joseph Anton: A Memoir (2012), Rushdie says, “All liberty required was that the space for discourse itself be protected.

Liberty lay in the argument itself, not the resolution of that argument, in the ability to quarrel, even with the most cherished beliefs of others; a free society was not placid but turbulent. The bazaar of conflicting was the place where freedom rang.” Exquisitely phrased, the deeper meaning here has a lesson for our times.

Rushdie wrote Knife because a book “about an attempted murder might be a way for the almost-murderee to come to grips with the event.” This ‘event’ shook the literary world more than 30 years after the publication of The Satanic Verses, the controversial novel published in 1989, which was banned in several nations. However, India was the first nation to take action because its allegedly blasphemous content angered many Muslims. The Rajiv Gandhi government banned the book’s importation because of the fear that it could cause law and order problems. Much worse happened after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, then Supreme Leader of Iran, pronounced a fatwa, asking Muslims to kill Rushdie for blasphemy in February 1989. The author soon realised his life had changed – and, not just for a fleeting while.

Some shared memories live longer than we often imagine. The consequence of one such shared memory was the Chautauqua episode in which a man attempted to kill Rushdie inside an amphitheatre. Strangely, the attacker had barely read a couple of pages of The Satanic Verses and watched some videos on YouTube. That motivated him to attack Rushdie, an act of violence that reminded everybody that the author was still not safe and secure. He had angered many Muslims across the world after The Satanic Verses was published. Their hatred has not lessened more than three decades later.

Knife would have been equally readable had it been written with a novelistic approach. The memoir, albeit a short 209-page one, has what it takes to create a story: violence, uncertainty, determination, hope, recovery, love (part of the book revolves around his relationship with his wife, poet, photographer and visual artist Rachel Eliza Griffiths) and family. The reader hears the voice of Rushdie, the writer of fiction, when he talks about his gradual recovery in his unique style, “All the stab wounds and gashes seemed to be closed. Even Dr. Pain did not need to squeeze any more saliva out of my face. Dr. Eye, Dr. Hand, Dr. Stabbings, Dr. Slash, Dr. Liver, Dr. Tongue – all began to sign off.” During such moments, his prose is characteristically dazzling, which is not a surprise.

Rushdie talks about his supportive friends. He discusses his need for privacy when he was recovering slowly, which resulted in measures to avoid the intrusive gaze of the world. He talks about his attachment to his family and dwells on his fractured relationship with his father. He lets his mind roam freely, using literary allusions and referring to films that enhance the memoir’s appeal.

A person who has grown up in a bookless environment might still know his name. That is because he has invited controversies, and not only because of The Satanic Verses. Former prime minister Indira Gandhi decided to take action against the book in 1984 because of a sentence in Midnight’s Children (1981). The sentence was: “It has often been said that Mrs. Gandhi’s younger son Sanjay (Gandhi) accused his mother of being responsible, through her neglect, for his father’s death; and that this gave him an unbreakable hold over her, so that she became incapable of denying him anything.” In the new introduction to the book for its 25th anniversary edition, Rushdie says, “When it became clear that she was also willing to accept that this was her sole complaint against the book, I agreed to settle the matter.” That was not the last controversy of his eventful life.

Rushdie cannot resist the temptation of discussing politics in Knife. Talking about India, he writes, “In India, religious sectarianism and political authoritarianism go hand in hand, and violence grows as democracy dies. Once again, false narratives of history are at play, narratives that privilege the majority and oppress minorities, and these narratives, let it be said, are popular, just as the Russian tyrant’s lies are believed.”

Has Rushdie been misinformed about India? Is he detached from modern-day Indian realities? Whatever the reason, he sounds like one of those Western observers whose acerbic attacks on India are based on distortions and falsifications. In a book about his life before and after an attempt to murder him, this digression is unnecessary anyway. Yet, Rushdie walks down that path, which will impress some and annoy the rest, simply because he is Rushdie.

(The writer, a journalist for three decades, writes on literature and pop culture. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views)

Comments

0 comment