views

There are 47 tiger reserves in India that are key to the survival of the beautiful beast, who continues to face threats from poachers and loss of habitat in the name of development.

In those reserves lives not just the tiger but the world's hope as India, where 60 per cent of the world's wild tigers are found, leads the endangered animal's conservation efforts.

That makes tiger reserves a component whose vital signs need to be continuously monitored, not just in terms of the tiger count but also the health of tiger habitat and prey population, which is critical to its survival.

The need was recognised by the Government of India that gave the responsibility of rating India's tiger reserves to Dr. Vinod Mathur - Director of the Wildlife Institute of India.

Dr. Mathur and his team has championed the project called Management Effectiveness and Evaluation of the Tiger Reserves (MEETR), having completed this four-year cycle twice.

Here, Dr Mathur himself decodes MEETR and how it's ensuring that the tiger's habitat stays healthy.

How you pioneered the Management Effectiveness and Evaluation of the Tiger Reserves in India in the year 2005-06?

All the tiger reserves have been established for conserving the tiger, and they are under good management, but how good is this management? Because the society is spending resources, both time and money, and manpower; and it wants to know whether these tiger reserves are being managed efficiently and effectively or not.

So this term - Management Effectiveness and Evaluation - is a a global framework, which, I would say, more than 100 countries in the world have adopted - not only for tiger reserves but for national parks and sanctuaries as well.

We looked at this framework and we realised that in a very objective manner, this framework helps us in assessing the level of effectiveness of management. But we then realised that the global things have to be, if I can say so, tweaked to meet the Indian situation. So we used the same framework but developed our own indicators. Over a period, we developed 30 such indicators, which basically, in common language, explain the health of the park or health of the tiger reserve.

We developed these indicators when the Project Tiger and National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) asked us.

In short, we can say these are the vital signs for tiger reserves.

Exactly, for the tiger reserve habitat and management. Not for the tiger but for their habitat and management.

But we wanted to keep this process independent. And that is where we went back to the Ministry, went back to the NTCA and said: "We as an institute will provide all technical back-stopping but our scientists and researchers will not be part of the actual evaluation process. So that was one way of looking at the independence of the system.

To make it more authentic

Yes, and to make it more vigorous. All assessments have to vigorous. If they lose vigour, they lose credibility. So we said framework is fine, indicators are fine, let's also put up a mechanism where assessment is also through an independent process. So we suggested a string of names to the government, they selected the names, and we thought we should put up a combination of a manager and a scientist. So there is a three-member team that goes to evaluate these parks based on the framework that we are providing. But that team is independent because they are not part of the government. Managers have experience of working (with wildlife) in the past, but they are not on the current payroll, i.e., they have retired but they have experience of tiger management. Same is true with researchers. They work independently, either as independent scientists or in civil society or in a scientific institution, but not as part of the government.

On that basis we have been able to do this evaluation for all 39 tiger reserves in 2010-11, and as we speak, there is a process going on for 2014-15. The tiger reserves will be evaluated and by end of this year, we will be in a position to know how well they are doing, rate them and compare with results of 2005-06, when we first did, and in 2010-11, when we did it for the second time. So a trend might also emerge when we look at these results.

Thanks for explaining the process. But there is a Phase IV in tiger estimation, which is an ongoing process - annually. So do you think this management effectiveness and evaluation should be implemented specifically for Phase IV as well to check it's effectiveness.

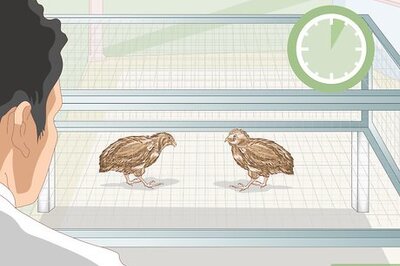

We are talking about two things, but they have a correlation. It's true that Phase IV monitoring is also being done and led by WII. We have scientists and teams in place, which are doing that, trying to estimate (tiger population). There is a very tenuous link between tiger numbers and management of effectiveness.

For a common man, it's like if the management is good, it should be reflected in higher tiger numbers. That's a common understanding. Though this understanding is correct, it may not always hold good. I will give you two examples.

Take the case of tiger population or numbers in a park called Ranthambore or Bandhavgarh. There the habitat and prey base is such that you will always find a higher number of tigers. Take the case now of Kalakkad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, take the case of Periyar Tiger Reserve. Even if the management is good, their tiger numbers cannot compete with the numbers in Ranthambore or Bandhavgarh. The dynamics are different, habitat are different, vegetation types are different.

So if a park gets a high score on MEE, it must have good population (of tigers) but that doesn't mean it will always have the highest number of tigers.

Comments

0 comment