views

"Who does Indu think she is? My wife has changed her diapers!" JP thundered

(The Prime Minister Indira Gandhi imposed Emergency on June 25, 1975. Her decision had shocked the entire World. Civil liberties were suspended and lakhs of people were sent to jail across India. This Thursday would be the 40th anniversary of those dark days in Indian democracy. Technocrat Ravi Visvesvaraya Sharada Prasad shares his personal memories of the Emergency days in this three part series he has written exclusively for IBNLive. His father the legendary HY Sharada Prasad was Information Advisor to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi till her death. He was one of the closest advisors to her and her son Rajeev Gandhi. Readers get a ringside view of what happened behind scenes before and during the Emergency)

The showdown between Jayaprakash Narayan and Indira Gandhi was a tense time for our family because my maternal uncle, KS Radhakrishna, head of the Gandhi Peace Foundation, was the principal aide and advisor of JP. The key interlocutors for the negotiations between Indira Gandhi and Jayaprakash Narayan were PN Dhar and my father on behalf of Mrs Gandhi, and my maternal uncle, KS Radhakrishna, on behalf of JP. PN Dhar had known JP decades before he joined Mrs Gandhi's staff, and he had won the total confidence and trust of JP. Some of the negotiating sessions took place in our residence. My younger brother and I would be told to go out and play.

The differences between Indira Gandhi and Jayaprakash Narayan turned out to be trivial, even petty. JP had a massive ego, and thought of himself as a wise sage, and as a truly worthy successor to Mahatma Gandhi. JP wanted Indira Gandhi to constantly run to him to seek his advice on moral and ethical issues, and was miffed when she did not do so. JP thundered to his aides: "Who does Indu think she is? My wife has changed her diapers!".

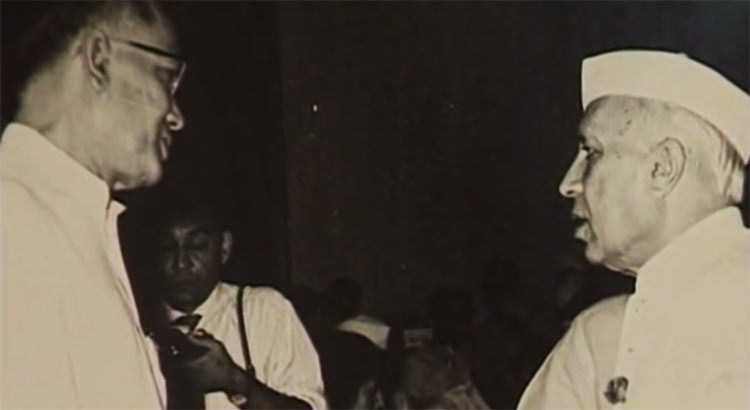

On the other hand, Indira Gandhi felt that JP had let her father down. For several years after Independence, Jawaharlal Nehru had thought of JP as the man to succeed him as prime minister. Nehru often asked JP to join his cabinet as his deputy, especially to tell him frankly where he (Nehru) was going wrong, to function as his internal opposition and moral compass, and to keep him (Nehru) in check from his self-avowed dictatorial tendencies.

But JP always declined Nehru's invitations to be groomed as his political heir and successor as prime minister, since he had a self image of himself as being a saint in the mould of Mahatma Gandhi, far above party politics and the nitty-gritty administrative business of running a government.

In addition, Indira Gandhi thought that JP changed his political views too often, from left wing to right wing, allowed political opportunists of all hues to exploit him, and was not too particular about the sources from which he received funds. Indira Gandhi accused JP of receiving funds from dubious foreign sources, which was true. (Although JP was personally incorruptible, and never kept a paisa for himself, he accepted funds for social and political purposes from all and sundry).

But the tense negotiations between JP and Indira Gandhi had their honourable human side as well. JP's wife had been the closest friend and confidante of Indira Gandhi's mother. When the negotiations were about to break down, JP handed over several large sealed packets with the instructions that they were to be opened only by Indira Gandhi personally, and that no one else was to see their contents. These contained the correspondence between Indira Gandhi's mother and JP's wife, in which Kamala Nehru had poured out her anguish over her ill treatment by Jawaharlal Nehru's relatives. JP did not want this personal correspondence containing Nehru family matters falling into the hands of his supporters and allies, who hated Indira Gandhi.

At the declaration of the Emergency, the only government officials present were BD Pande (then cabinet secretary), PN Dhar, and my father. PN Dhar and my father whispered to each other that they had been witness to an evil act. None of the cabinet ministers - Jagjivan Ram, YB Chavan, Sardar Swaran Singh, K Brahmananda Reddy, etc voiced any objections over the declaration of the Emergency. Most of them had no inkling at all of the arrests of opposition leaders the previous night.

I now seem to recall that my father came home the previous night at 2 am, slept for a couple of hours, and left again at 4:30 am. He was very tense and worried, and extremely fatigued, but did not utter a word. The next morning, he called my mother shortly before 8 am from his office, and told us to switch on All India Radio. It was then that we heard Indira Gandhi's proclamation of the Emergency. Most of the newspapers did not come that morning. Only The Motherland, the organ of the Jana Sangh, The Hindustan Times, and The Statesman, were delivered to our home. The Motherland of the Jana Sangh had huge stories giving complete details of the arrests of all the opposition leaders all across the country. It was a real journalistic and reporting coup on the part of The Motherland. This was to be its last issue.

The best description of my father's role is given in Bishan Narayan Tandon's book.

Excerpts from PMO Diary -I, Prelude to the Emergency, written by BN Tandon, and published by Konark Publishers:

26 June 1975

"...As I was leaving for the office, Sharada phoned to say, "You must have heard, it is all over. We will talk when you come to the office." He sounded very dejected.

On reaching office I went straight to Sharada's room. He told me in detail whatever he knew. Last night the PM had summoned him and Prof Dhar to her house at 10 pm. [Congress leader Devkant] Barooah and [Siddharth Shankar] Ray were already there. When Prof Dhar and Sharada reached there, the PM told them, "I have decided to declare an Emergency. The president has agreed. I will inform the cabinet tomorrow." Saying this, she handed over the draft of the Emergency proclamation to Prof Dhar. He and Sharada were stunned. They had been summoned only in order to be informed and for their advice on the propaganda to follow. She also told them to prepare a draft of her address to the nation. They were at the PM's house till about 1 am. The cabinet was to meet at 6 am.

All those ministers who were in Delhi attended the cabinet meeting. The PM told them what she had decided to do but not one of them protested, not even faintly. Only Swaran Singh raised some administrative issues. The arrests were not discussed at all. One of the ministers said that he had heard about the arrests but the matter was swept aside. Even Prof Dhar had no idea of these arrests. Sharada said that all the main leaders of the opposition, including JP [Jayaprakash Narayan], Morarji, Charan Singh have been arrested.

Sharada also told me that Sanjay was now in full control of the PM's house. After the cabinet meeting he called Gujral to one side and scolded him for the poor propaganda effort. He told him to send every new bulletin to the PM's house henceforth: Gujral told him that from the functional point of view, some official should be deputed for this. He could be stationed at the AIR, where he would be shown all the bulletins. He suggested Sharada's name for this but Sanjay put Behl on the job.

VR also joined us. After hearing Sharada he said that henceforth India too would have a "guided" democracy. Sharada said yes in a very low tone.

He was very tired. Since June 12 he has had to work the hardest in the PM's secretariat because the PM's entire strategy is based on propaganda. But more than physical tiredness, he was in mental agony. I have never seen him like this. He must surely have wondered if this was what he had gone to jail for in 1942. He is a journalist. After independence this is the first time that pre-censorship has been imposed….

Seshan came very late to the office today and came straightaway to my room. He said, "See I had told you. But I don't know what will happen next. Sanjay has taken control completely."

I was very depressed the whole day. I felt very bitter as well. Is democracy coming to an end? I did not stir out of my room. I didn't even go to see Prof Dhar. What was the point? I can understand his pain. I thought that all emergency-related work would be new and I didn't really wish to handle it. I talked to Behl to look after it. After all, he has been brought in not only to look after the additional work but also to gradually take over my work. I kept asking myself how restless Nehru's soul would be today."

My father again offered his resignation to Mrs Gandhi in protest against censorship of the press, but she refused to accept it, adding that she had several cogent reasons for imposing the Emergency. My father told her that this was not what he went to jail for in 1942, during the Freedom Struggle.

To overcome my father's vehement objections, Indira Gandhi showed him some intelligence reports and transcripts of intercepted communications. Some of these related to Jayaprakash Narayan exhorting the armed forces to revolt, and to the sources funding JP and George Fernandes. There were personal messages from Leonid Brezhnev, marked for her eyes only.

Then when Sheikh Mujibur Rehman was assassinated on the politically significant day of August 15, 1975, she told my father as they were driving to Red Fort for her Independence Day address to the nation: "You were opposing the Emergency. Now you know why I was compelled to impose the Emergency. India was next".

Many decades later, my father stated in a lecture: "If Indira Gandhi had thrown in the towel at that point of time, it would have greatly weakened the Indian state...The Emergency did damage our democratic roots badly, but the state had been saved from a very grave challenge…" My father never revealed anything more than this, refusing to answer questions even from his closest friends and relatives.

Professor PN Dhar wrote in his book Indira Gandhi, the 'emergency', and Indian Democracy

What led Indira Gandhi to take such a drastic step? Did she have to pick up the gauntlet thrown down by JP on the Ramlila grounds? There is no simple answer. Her problem was much more complex than JP's, for whom what was happening in the country was like a medieval morality play in which all the angels were on his side. He had no dilemmas, his mind was full of certitudes. He was more attuned to the rhetoric of revolution than to the complexities of administering a difficult country.

Indira Gandhi's situation, on the other hand, was agonising for her. Not only was her own political future at stake, her party was under severe strain by the infighting and factionalism. Above all, she was the prime minister and she had to worry about the consequences of her exit on the governance of the country. Her mind was a jumble of all these personal and public concerns, which were not easy to disentangle.

First, her personal interest. She was aware that if she resigned even before the Supreme Court could rule on her appeal, she would impress some sections of public opinion and could probably come back to power if the court decided in her favour. Had the opposition leaders, particularly JP, left the onus of the decision entirely to her, it is not improbable that she would have resigned. But they were keen to exploit the situation, exercise their newly gained strength, and demonstrate that they had forced her to resign. Even before she could file her appeal, to which she was entitled, a delegation of opposition leaders from the Congress (O), JS, BLD, SP and Akali Dal called on the President and presented a memorandum to him saying that 'a grave constitutional crisis had arisen as a result of Mrs Gandhi continuing to occupy the of office of the Prime Minister despite a clear and categorical judicial verdict. They pressed for her resignation. In their public utterances she was mercilessly demonised.

This exhibition of personal animus brought out the fighter in her and strengthened her resolve to defend herself. She was also worried about the goings on in the party. Though the Congress Parliamentary Party had reiterated its 'fullest faith and confidence' in her leadership, she was unsure about her pro-tem successor's attitude. Would he let her comeback? He might rattle some skulls in the cupboard, especially the ones in that of her son Sanjay, to keep her out of office. Such were her personal worries.

As regards her public concerns, Indira Gandhi was almost certain that her party would split if she resigned even temporarily. She was unsure about the intentions of Jagjivan Ram and so-called young Turks like Chandra Shekhar, who had not forgiven her for not compromising with JP. Her worst fears were about the opposition coming to power; it was a spectre that haunted her because she believed it would be a disaster for the country. She agonised over all these considerations.

All these cogitations and counsels came to an end on June 24 when Justice Krishna Iyer of the Supreme Court, before whom she had moved her appeal for absolute stay order against the Allahabad high court judgement, granted her only a conditional stay, which meant that she could continue as Prime Minister but not function as a full voting member of the Lok Sabha. This was the fateful moment of decision for her. Feeling diminished in her authority by Justice Iyer's verdict to cope with the threatened disorder that was looming large - the opposition parties announced their plans of countrywide satyagraha - she pressed the panic button and her contingency plan for the declaration of an internal emergency came into operation.

When the fateful moment arrived, JP did not let the law take its own course. Whether it was his mistrust of Indira Gandhi's motives, or his own lack of faith in the democratic method, or his ambition to go down in history as a political messiah of the Indian people is beside the point. Similarly, Indira Gandhi showed more faith in the repression of political opponents and dissidents in her party than in her own ability to engage them constructively or fight them politically. Whether she opted for the Emergency to save herself from loss of power or as shock treatment to bring the country back to sanity is also beside the point. The fact remains that both JP and Indira Gandhi, between whom the politics of India was then polarised, failed democracy and betrayed their lack of faith in the rule of law.

(The last and the third part of this series will be published on June 25)

(Ravi Visvesvaraya Sharada Prasad, an alumnus of Carnegie Mellon University and Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, is a consultant in telecommunications and information technology. He has four masters degrees in engineering and science)

Comments

0 comment