views

Recording Expenses in Journals

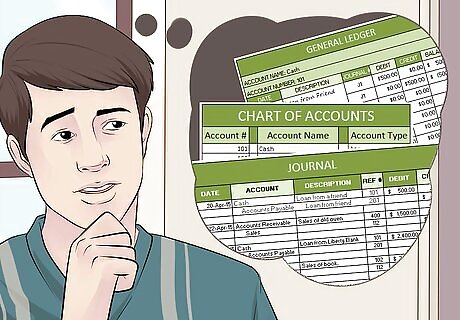

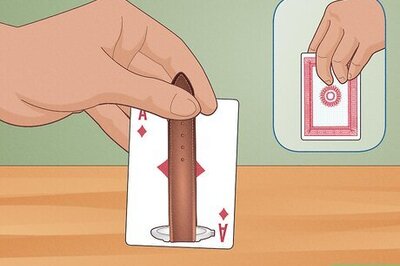

Know that a journal is a list of every transaction your company makes. An accounting journal records the details, date, and amount of all the money flowing in and out of your business. It is non-specific, meaning that you record everything in the journal no matter where the money is going. You must first post your transactions in a journal before your post them in a ledger.

Save copies of all your business receipts, invoices, and debts. You need to have accurate documentation to create an accurate accounting journal and ledger, so save everything you have that relates to finances for later use.

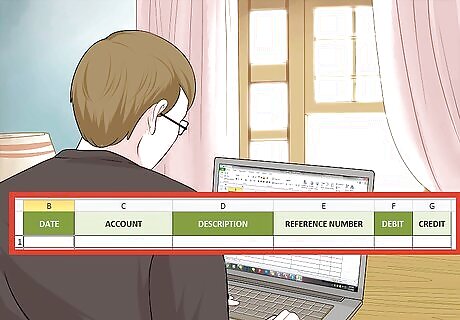

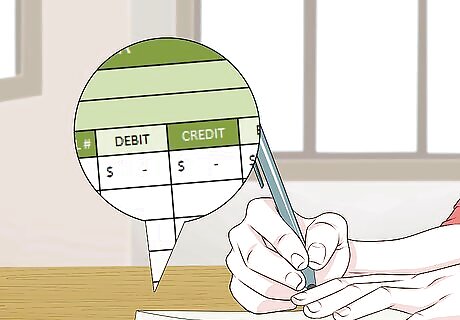

Set up your journal page. Using a spreadsheet or a computer accounting program, begin a new journal page by dividing the page up into five columns: Date Account Description Reference Number Debit Credit

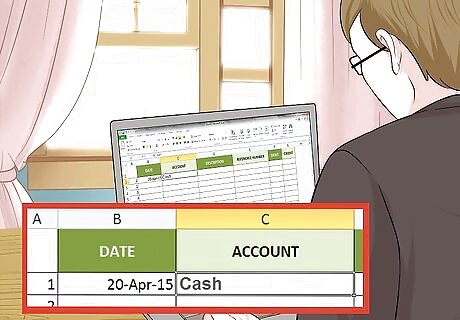

Record transactions the date that they occur. Under your “date” heading, mark when a transaction was made. You should have a journal for every type of interaction your business does. If you receive a $500 check for your business on April 20th, 2015, start the journal entry with 4/20/15. You need accurate dates for accurate bookkeeping. Find a time at least once a week to log all of your journal entries to make sure you don't lose any.

Categorize the “account” of the transaction. This is where the vocabulary of accounting is especially handy. Accounts are ways to think of how your money is being spent or earned. For example, the $500 check adds to your business's cash, so it would be labeled 4/20/15, Cash. Some of the most common accounts include: Cash: Money that your business has on hand. This is not necessarily hard cash. If someone writes your business a $500 check, for example, it would be an increase in cash. Accounts Payable: These are business expenses you owe. For example, if the $500 check you received is a loan, you need to note $500 under your accounts payable journal. Accounts Receivable: This is money that your business is owed. General Journal: This journal is essential to capture all weird or one-time transactions, like bad debts, inflation, selling equipment, etc. Sales: The the revenue generated by selling your business's product. Equipment, Wages, Land These three accounts, usually separate, detail the expenses needed to keep your business running.

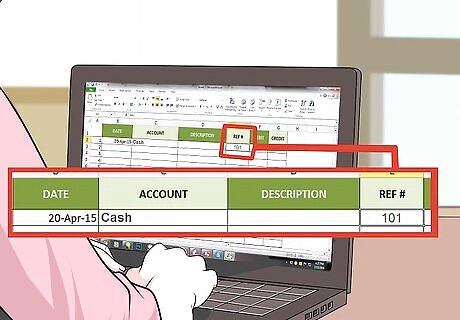

Assign each account a number for easy reference. This is usually referred to as your “chart of accounts.” Usually, similar accounts are listed near each other, so you might label Wage Costs 501, Utility Costs 521, and Advertising Costs 531. This helps you easily order and reference your different accounts later on. For example, if you decide to label “Cash” as 101, then you can mark your check as 4/20/15, Cash, #501. The space between numbers (501 and 521) is so you can add new entries in between them. For example, if you are using physical books, or want to start a new journal every year, you might label “Wage Costs” as all account numbers 501-520, one for each of the next 20 years.

Record the details of your transaction. After listing the date, account, and reference number, briefly describe the transaction. This only needs to be enough information to accurately remind you where the money came from or why it was spent. With the check example, you would write 4/20/15, Cash, #501, Check from Friend. Some other examples of descriptions include: ”Loan from Liberty Bank.” ”Money from tax return.” ”Sale of old oven.” ”Repairs to factory roof.”

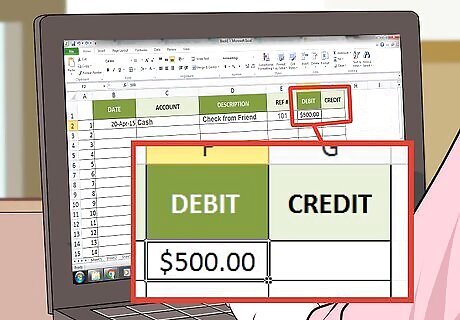

Note whether the transaction was a debit or a credit. Debits are assets, or things that increase the worth of your business. For example, if you earn $500, you list it as debit. Credits are expenses, or liabilities, of your business, like loans or accounts payable. Simply list the amount of money spent or received under each account. For the check, you write out 4/20/15, Cash, #101, Check from Friend, $500 Debit. Debts and credits cancel out. For example, if you spend that $500 on a new oven for your bakery, you would note a $500 debt (Equipment) and a $500 credit (Cash). While you gain $500 in equipment value, you lose $500 in cash. Common debits include cash, accounts receivable, equipment, land, wages, and personal funds. Common credits include: cash spent, accounts payable, bills, mortgage, and loan payments. Remember -- debits are assets and credits are liabilities.

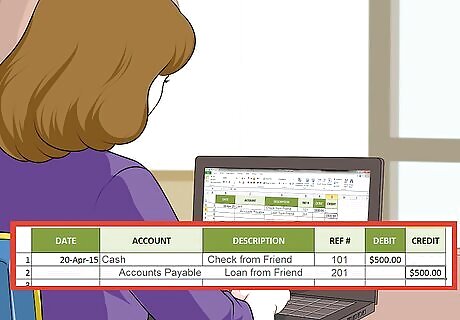

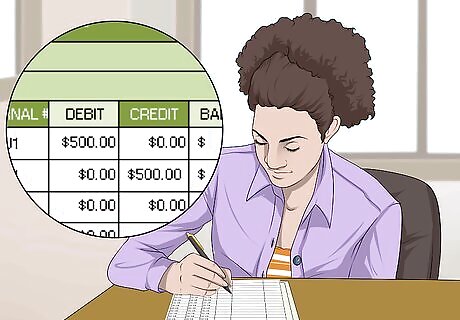

Use separate lines for transactions that apply to multiple accounts. For example, that $500 check you received for your business might be a loan, meaning you would have to write it down as both “Cash” and “Accounts Payable. Use separate lines under the same date and description to note both accounts and their amounts. 4/20/15, Cash, #101, Check from Friend, $500 Debit Accounts Payable, #201, Loan from Friend, $500 Credit

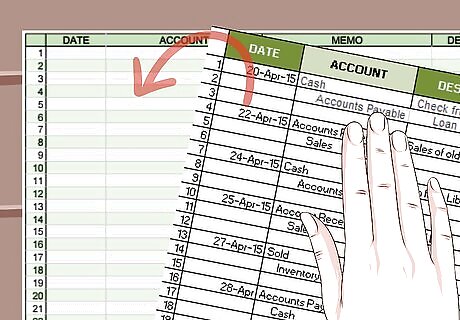

Record every single transaction as it happens. Every time any one of your accounts makes a change, record it in your general journal. Think of this document as the “story” of your finances – it tells the details of every economic interaction your business made in order. At the end of the day or week, take all of your receipts and invoices and check them against your journal to make sure you haven't missed anything.

Label your journal. Just like you labeled every single account, you should make a label for your journal. An example might be by date, such as “General Journal for 4/1/15 → 5/1/15,” or by simply using numbers to place journals chronologically, such as “Journal 1.”

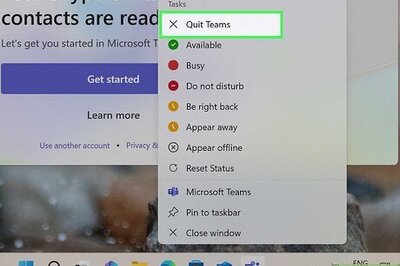

Transfer your journal entries to account ledgers regularly. An account ledger notes every transaction by account -- so you have a ledger for Cash, Accounts Receivable, etc. You need to keep both a journal and a ledger so that executives, accountants, and staff can quickly look up your business's financial health by date and by type. If possible, make a record in your ledger immediately after writing in the journal.

Writing Account Ledgers

Use account ledgers to keep track of specific transactions like cash, accounts receivable, or sales. Journals are where you write the date, details and amount of every single business transaction based on its type. But ledgers break this information up into specific accounts, allowing you to see all of your transactions, like Cash, Accounts Receivable, Sales, on their own sheets.

Make a ledger page for each account. Make specific account ledgers based on their name and reference numbers. Your first ledger might be "Cash, #101." This ledger will illustrate every single cash transaction you've made. You will copy your journal entries into the appropriate ledgers, so you need a ledger for every account listed in your journal. Consider making a "Chart of Accounts" table of contents page to help you keep track of each account number. If you have odd expenses, consider a “general ledger” as well, which collects atypical transactions like tax returns, sales gone bad, personal expenses, etc.

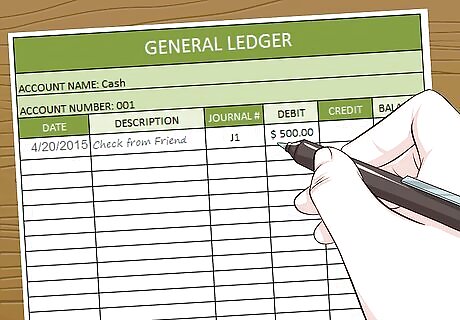

Make columns on the far left of the page for the date, journal number, and description. These can be copied directly from your journal entry on the transaction. For the $500 check, you can list “4/20/15, Journal 1, Check from Friend.”

Split the rest of the ledger into three sections: Debit, Credit, and Balance. This allows you to quickly see what you own (debit), what you spend (credit), and how much you still owe (balance.) Your final sheet should look something like this:Date | Reference | Description | Debit | Credit | Balance | In a ledger, just like in a journal: Debit refers to money you receive. Credit refers to money you owe or paid. Balance refers to the what you still owe, or the difference between debit and credit.

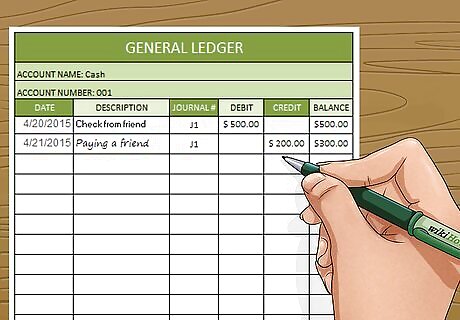

Place any related credits and debits side by side. For example, if you have a $500 loan from a friend, start by noting down $500 as a debit. Say you make your first sale for $200 the next day and decide to start paying your friend back. Mark a new date, 4/21/15, and write $200 under your credit section.

Use the balance section to calculate how much money you've earned or still owe. With the last example, you paid back $200 of the $500 loan your friend gave you. Subtract the payment you've made from the total you owe to find you balance. Here, you still owe $300, so note that as your balance to the right of your payment. In other words, the Balance = Credit – Debit. Not every expense will have a balance. If, for example, you receive a $20,000 research grant that you don't have to pay back, you just note the $20,000 in the debit column and move on.

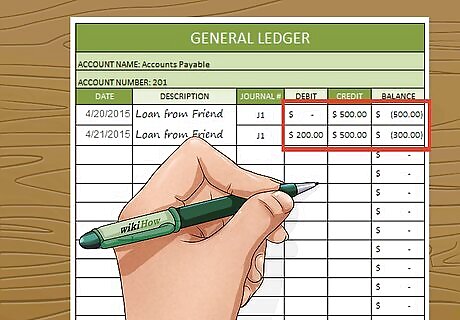

Remember to make related entries in every account. Returning to the $500 loan from a friend, you must also note that you owe them the money in “Accounts Payable:/4/20/15 | Journal 1 | Loan from Friend | $0 Debit | $500 Credit | $500 Balance | This must occur every time there is a change to the account. If you decide to pay your friend back, for example, you would need to make a new entry/4/21/15 | Journal 1 | Loan from Friend | $200 Debit | $500 Credit | $300 Remaining |

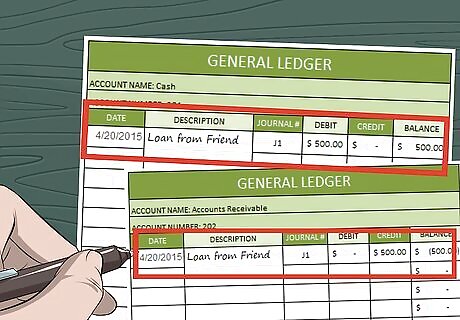

Record transactions as they occur. Any time a journal entry is made, that entry should be immediately posted to the ledger. For our example, we have the journal entry: Loan from a friend for $500. This journal entry affects 2 accounts (Cash and Accounts Receivable), so you must make entries to both of those ledger accounts. Turn to the Cash page of your ledger. In the left column (which is used for recording debits), write the date of the transaction, and then write the amount. In this example, the amount is $500. Turn to the Accounts Receivable page of your ledger. Write the date in the right column (which is used for credits), followed by the transaction amount. In this example, the amount is $500. Update these pages as new journal entries arise.

Add a “notes” section to help track new information. For example, once you've paid off your total loan of $500, you might write out “Paid in Full” under the description, or a small notes section next to “Balance.”

Combine different accounts into one book to build your general ledger. A full ledger details every single account so that anyone can flip through it to see exactly how much money is being made/spent in each category. The front page includes the chart of accounts, listing each account in the ledger and its number, such as “Cash, #101,” so that people can easily find the information they need. Add the accounts to the ledger in order for easy access.

Add up the debits and credits at the bottom of the page for each account. This lets you know the total amount you own or owe for each account. If the credits are higher than the debits, then that account is in losing money. This however, is to be expected – accounts payable will always be in debt, because it is a list of all the money you owe.

Add together your total debits and credits and make sure they match. Debit will always equal credit. This is an ironclad rule of accounting, and it makes sense: all of your money had to come from somewhere. If you bought something, you paid for it (credit) and now own it's worth (debt). If there is any discrepancy, check your journal against your ledgers to find anything you forgot to record. Remember – any transaction, positive or negative, needs to go into the journal and ledgers. Some beginner accountants often forget the idea of “ownership.” For example, if you spend $10,000 on the business, then the business technically “owes” you $10,000. If the business was ever sold, you would be paid back your $10,000.

Review how to craft a balance sheet if you are struggling to account for all your debts and credits. Balance sheets are snapshots of your business's assets and liabilities. This helpful form lists everything your company owns and owes at any given time, which can help you see any holes in your ledger.

Familiarize yourself with the accounting cycle to learn what comes next. Posting to the general ledger is step 2 in what is known as the accounting cycle. On its own, the ledger wouldn't be very helpful, but used as a part of the cycle, it is an invaluable tool. The accounting cycle can be broken down into a few simplified steps. Collect the source documents, like receipts or invoices, that need to be logged. Record the transaction in the journal in chronological order. Post the journal entries to the ledger accounts. Prepare the trial balance. This is a listing of all the ledger accounts pooled together, and it should be prepared at the end of the accounting period. Prepare the financial statements. These can be compiled after adjusting the trial balance properly.

Comments

0 comment