views

Understanding the Staff

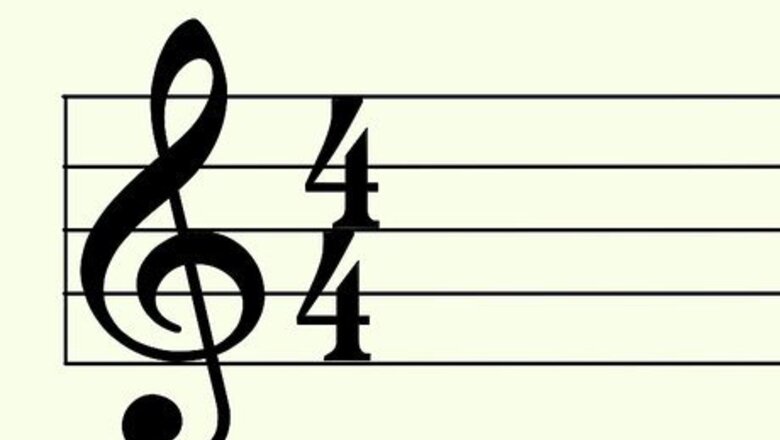

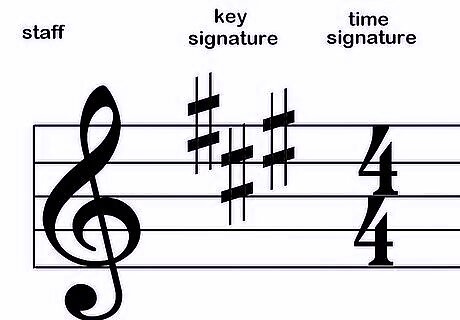

Recognize the musical staff. You know you have written music when you see five lines, capped off on the ends. On the far left will be a "clef" (a italicized "G" or "C" shape), a set of numbers, like 4 4 {\displaystyle {\frac {4}{4}}} {\frac {4}{4}}, and a set of hashes or flats denoting the key. Together, these elements make up a musical staff. Guitar is also written as "tablature," a unique music-writing system for guitar. Tabs resembles traditional musical staffs but have six lines instead of five, no clef, and often say "Tab" on the far left side. Guitar music is always written in "treble clef." This means the symbol on the far left is always a cursive G, with the bottom looping around the second-lowest line of the staff.

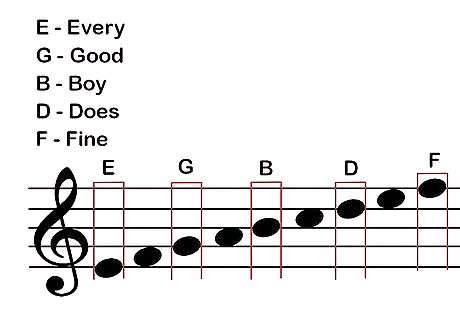

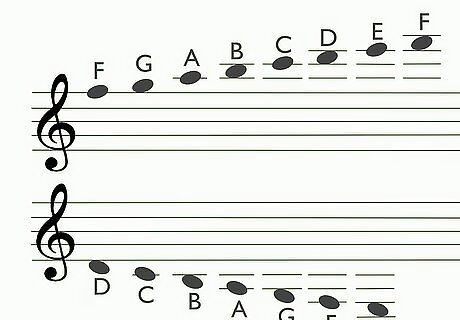

Memorize the notes of each line in the staff using the acronym "Every Good Boy Does Fine." Each line in the staff signifies a note, like an A, an E, etc. When there is a note symbol on the line, you play that note -- but you have to know which line is which note. Starting from the bottom, the notes are E - G - B - D - F, or the acronym "Every Good Boy Does Fine"

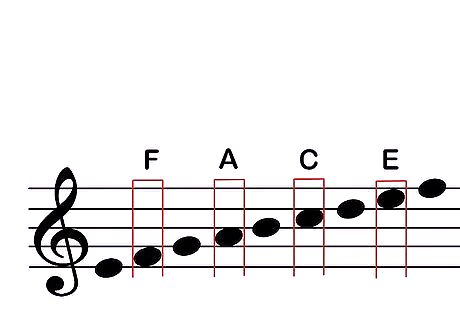

Memorize the spaces between the lines using the acronym "FACE." The spaces in between the lines also denote notes, meaning that the staff, in total, covers nine different notes (not counting sharps and flats, which will be covered later). From the bottom up, the spaces signify the notes F - A - C - E, or "FACE." Including the spaces, the final staff from the top looks like: F E D C B A G F E

Use lines above and below the basic staff, known as ledger lines, to get higher and lower notes. If you see small little lines above and below the staff, these are simply to extend the range of the sheet music beyond the five lines on the staff. Each line has a note above and below, and you need to memorize it as you move forward. For now, however, just work on the basics.

Read the key signatures, made of sharp, flat, and natural signs, to know what key the song is in. The key signature is between the staff and the time signature. It will be made up of some combination of three signals -- ♯, ♭, ♮ -- lined up on the staff. You'll need to memorize key signatures to know them -- the one in the video above is the key of D. However, they still give useful information if you don't know the key: Depending on what line the symbol fall on, you adjust that note. In the example above, there is a sharp on the F line, and one on the C space. This means any note on these lines you 'must make a sharp. This automatically keeps you in key.

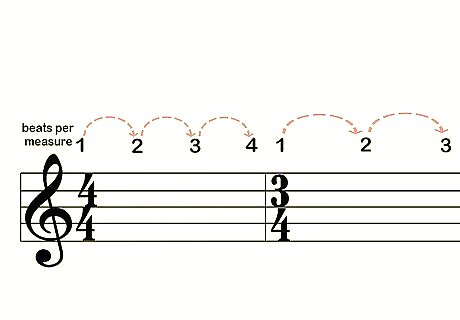

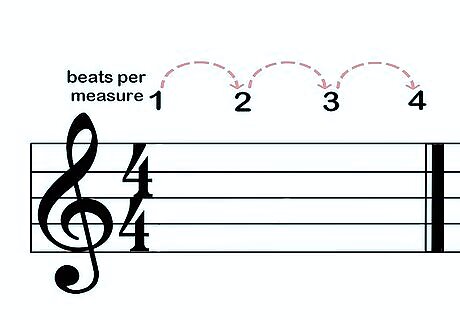

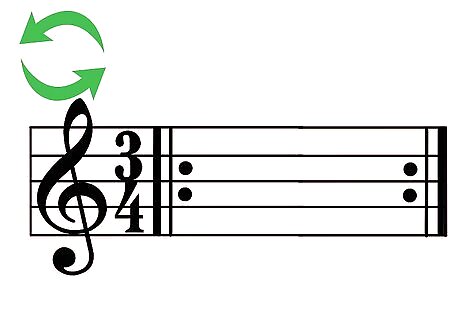

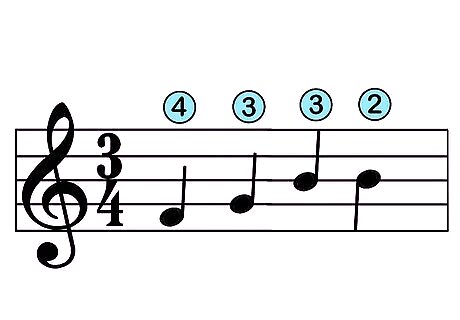

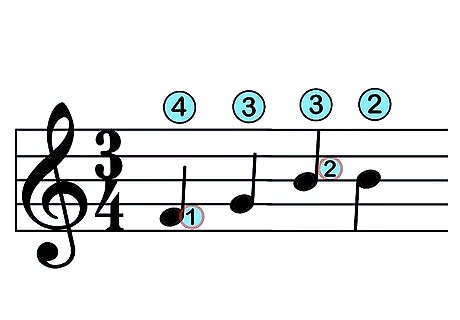

Use time signatures to determine the rhythm of the song. Time signatures tell you how many beats per measure in the song. The most common is 4 4 {\displaystyle {\frac {4}{4}}} {\frac {4}{4}}, which means that each measure consists of "four quarter-note beats." This is just a complicated way to say you count out "1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4, 1... etc." to keep time with the song. Other time signatures, like 3 4 {\displaystyle {\frac {3}{4}}} {\displaystyle \frac{3}{4}}, changes the number of beats in the measure -- in this case "three quarter-note beats," as in "1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1...."

Use the vertical bars in the staff to find the end of each measure. There are often numbers above each line, telling you which measure you're on to help coordinate with a band.

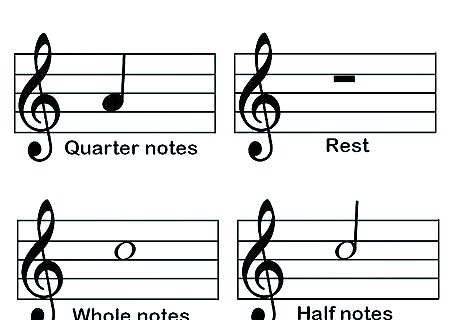

Recognize the different types of notes. The placement of a note on the line or space tells you what note to play -- they type of note tells you how long to play it. A whole note is played for the whole measure, a half note for half a measure, and so on down to thirty-second notes. For now, just get used to the different types of notes you're likely to encounter: Whole notes: O Half notes: A whole note with a vertical tail, a quarter note with a hollow center. Quarter notes: ♩ Rests: are times to not play -- they are either thick "--" marks for whole and half rests and squiggles for quarter note rests.

Understanding Complex Notations

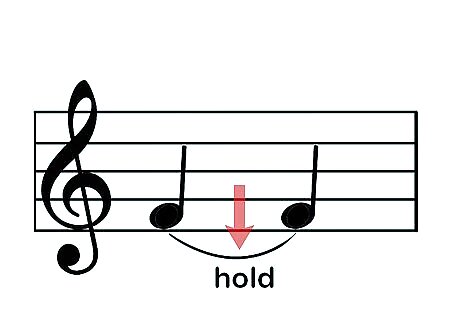

Hold notes for lines curving underneath two or more notes. If there is a concave line between two notes (it bends downward), then you want to hold the notes

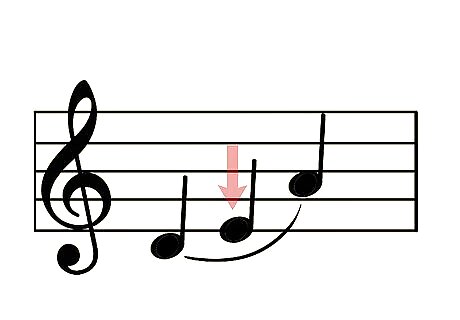

Let lines arcing over notes tell you when to hammer on and pull off. This is known as "legato," where every note is slightly blended together. Use hammer-ons and pull-offs to glide between these notes as seamlessly as possible.

Repeat any sections book ended by the bold, vertical "repeat" sign. These come at the end of a measure. The normal vertical bar is bolded, with a colon (:) right before it. This means you go back to the last time you saw a symbol and flipped it horizontally and repeat the playing until you get back again.

Use the string indicators to know which specific note you're supposed to play. Do you play the A on the fifth string or the second? Guitar tab will have a helpful number circled above the note telling you which string to play on.

Use finger indicators next to the note to help with positioning. If there is a small number next to the note, it is telling you to use a specific finger. Your first finger is your index finger, your fourth is your pinky.

Research more complicated notes and notation as you grow as a musician. There a lot more notes out there that, while less common in guitar music, are worth knowing. The first thing that you should explore are different notes -- from sixteenth notes down the eighth note rests. Check out the general "How to Read Music" to get deeper insights into music theory and expand your knowledge past just guitar music.

Comments

0 comment