views

Searching for Wet Areas

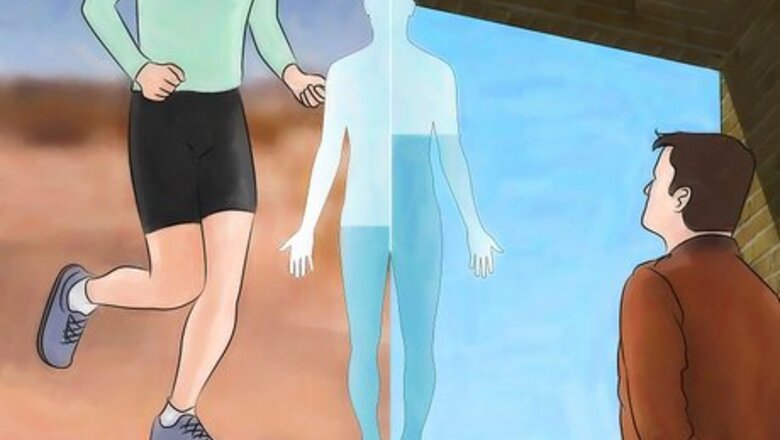

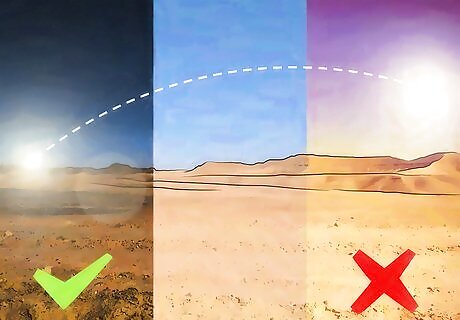

Slow your rate of water loss. Exercise and sun exposure will speed up dehydration. Be smart about when you search for water. If possible, spend the hottest parts of the day in a shady location away from wind. Keep your skin covered to reduce water loss from sweat evaporation.

Follow wildlife. A group of animals almost always means water is nearby. Look for the following signs: Listen for birdsong and watch the sky for circling birds. If you encounter swarms of flies or mosquitos, look nearby for water. Bees often fly in straight lines between water sources and the hive. Keep an eye out for animal tracks or trails, especially ones leading downhill.

Look for vegetation. Dense vegetation and most trees cannot survive without a steady water source. If you are unfamiliar with local vegetation, aim for the greenest plants you can see. Deciduous and wide-leafed trees are typically a better sign than pine trees, as they tend to require more water. If you can identify local plants, see below for species to look for. In North America, look for cottonwoods, willows, sycamores, hackberry, salt cedar, arrow weed, and cattails. In Australia, look for desert kurrajong, needle-bush, desert oak, or water bush. Keep an eye out for mallee eucalypts, or eucalypts that grow with multiple stems emerging outward from the same underground tuber.

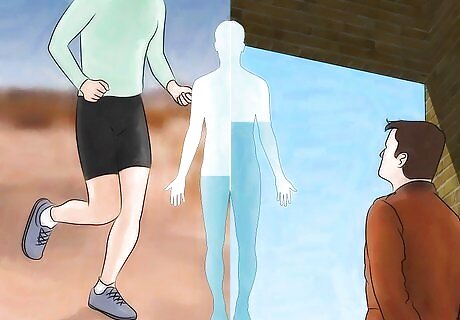

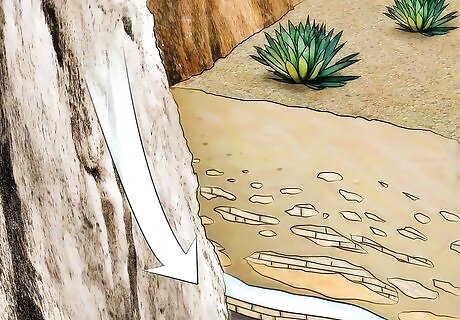

Search up canyons and valleys. Your best bet is a canyon that stays shaded during the hot afternoon, upstream of the mouth. This means a north-facing canyon if you are in the Northern Hemisphere, or a south-facing canyon in the Southern Hemisphere. Find these with a topographical map if you have one, or eyeball the surrounding landscape. Snow or rainfall is more likely to be retained in these cooler canyons, sometimes for months after a major rainstorm.

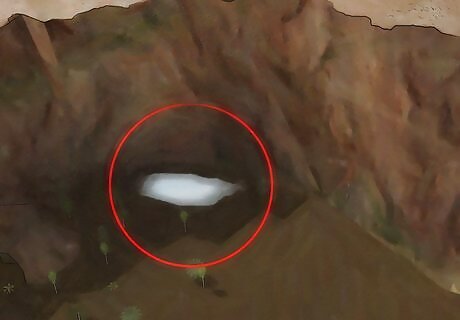

Find dry stream or river beds. Sometimes you can find water just under the surface. The best place to look is at a bend in the river, on the outside edge. The flowing water may have eroded this area down, creating a depression that catches the last dregs of water.

Identify promising rock features. Groundwater tends to collect at the dividing lines of a landscape, at the foot of mountains or large rock outcrops. Ideally, dig where a hard, impenetrable rock slopes beneath the surface. Softer stone such as sandstone can develop pockets that hold water for a while after a rainstorm. If it's rained fairly recently, search along level expanses of these stones, or at the top of boulders and isolated domed outcrops.

Find sand dunes near the beach. If you're near the ocean, the sand dunes along the beach may trap and filter the seawater. Digging above the high tide mark may reveal a thin layer of fresh water, sitting on top of heavier saltwater.

Find high ground if you see no other options. A hike to the high ground gives you the best vantage point to look for the features mentioned above. Try this as a last resort, since the exercise will dehydrate you — and you likely won't find water at the top of a hill. When the sun is low in the sky, look for the glare of a reflection on the ground. This may be a body of water. If you are in an area used for cattle, you may see artificial water collection features at the base of gently sloping ground. Carry a pair of binoculars with you anytime you are out in the desert. This can help you spot areas where you might find water from a distance.

Digging for Water

Choose a likely spot. Once you've reached an area that seems promising, take a look around for surface bodies of water. In most cases, you won't be this lucky, and will have to dig instead. Here are the best places to do so: At the base of sloping rock features. Near dense vegetation pockets, especially where bulges and cracks may indicate tree roots. Anywhere the surface soil feels damp, or at least more clay-like than sandy. At the lowest point in the area.

Wait until a cooler part of the day (recommended). Digging during the afternoon is risky, since you'll lose sweat to exposure. If you can afford to wait, stay in the shade until the temperature starts to come down. Groundwater tends to be closest to the surface in the early morning, especially in areas with vegetation.

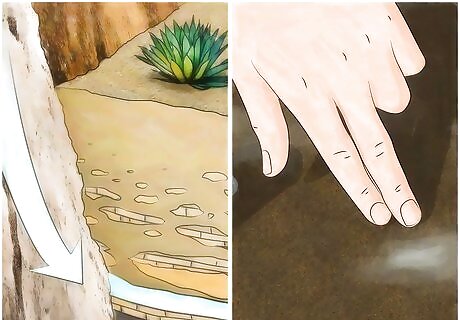

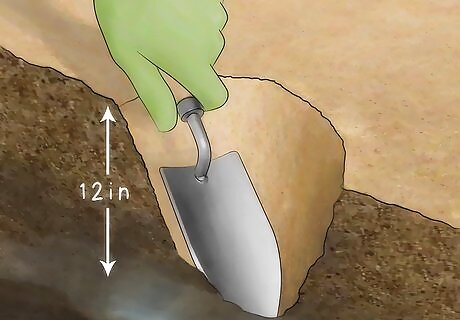

Look for moisture about a foot under the surface. Dig a narrow hole about 1 ft (30 cm) deep. If the ground is still dry, move on to a different spot. If you notice damp soil, move on to the next step.

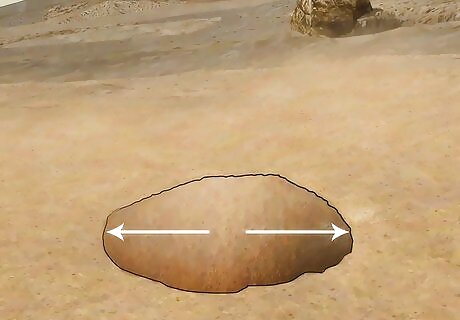

Enlarge the hole. Expand the hole until it is about 1 ft (30 cm) in diameter. You may notice water seeping in from the sides, but finish digging even if you don't.

Wait for water to collect. Return to your hole after a few hours, or at the end of the day. If there was water in the soil, it should collect at the base of your hole.

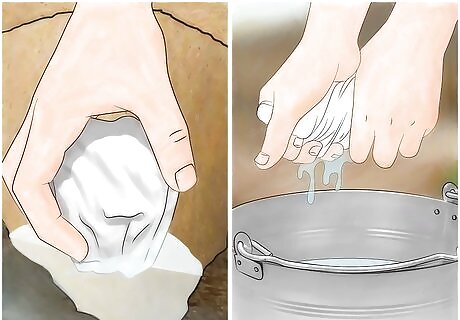

Gather the water. If the water is difficult to reach, soak it up with a cloth and squeeze it into a container. Collect all the water right away, using makeshift containers if necessary. Water holes can empty fast in the desert.

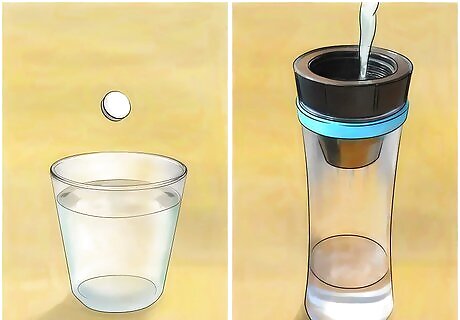

Disinfect the water (recommended). Whenever possible, purify the water before drinking it. Boiling the water, using iodine tablets, or pouring it through an anti-microbial filter will remove almost all biological contaminants. Infections from contaminated water may cause vomiting or diarrhea, which dehydrate you rapidly. However, these infections often take a few days or weeks to cause serious symptoms. Drink the water now if you're in an emergency situation, and visit the doctor when you're back in civilization.

Other Places to Find Water

Collect dew. Look for dew drops on vegetation before dawn. To gather it, pass an absorbent cloth over the dew, then squeeze it into a container. If you don't have absorbent cloth, form a clump of grass into a ball and use that instead.

Search in tree hollows. Decaying or dead trees may contain water inside the trunk. To reach into small holes, tie a cloth around a stick and fit it through the hole to absorb water. Insects entering a hole in the tree may be a sign of water.

Look for water around and under rocks. Rocks slow evaporation, so dew or rainwater may linger around them a little longer. Turn over half-buried stones in the desert just before dawn and dew may form on their surface. (This works because the base of the stone is cooler than the surrounding air.) Check for scorpions and other animals before reaching underneath rocks.

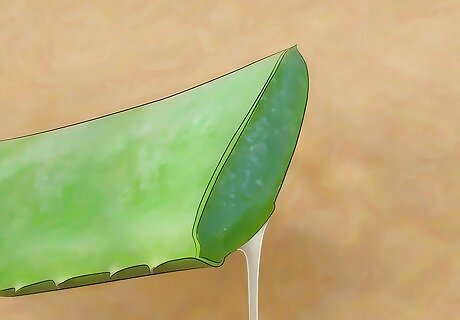

Eat cactus fruit. These juicy fruits are safe to eat and contain enough moisture to supplement other sources. Collect the fruit carefully to avoid injury, then roast them in a fire for 30–60 seconds to burn off the spines and hairs. You can eat prickly pear cactus pads as well. They are best when gathered young in the spring, then cooked. During other seasons they may be tough and hard to eat.

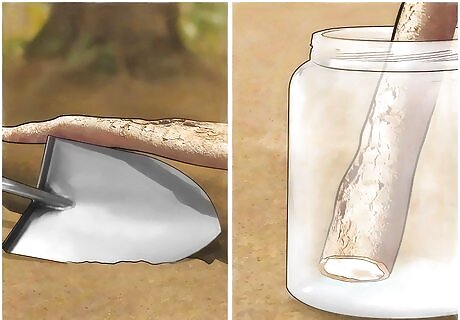

Collect water from eucalyptus roots (Australia). In Australian deserts, the mallee eucalyptus is a traditional source of water, though it can be difficult to access for an untrained person. Each eucalyptus looks like a grove of small to medium trees, growing outward from a single underground plant. If you see a eucalyptus that matches this description, try to get its water as follows: Dig out a root where you see a bulge or crack in the ground, or look for them at about 6.5 – 10 ft (2–3 meters) from the tree. The most promising roots are about as thick as a man's wrist. Pull out the length of the root, breaking it off near the trunk. Break the root into pieces 1.5–3 ft (50–100 cm) long. Stand the roots on end in a container to drain. Look for additional roots. There are usually 4-8 near the surface around each mallee eucalyptus.

Drink barrel cactus water only as a last resort (North America). Most barrel cacti are poisonous. Drinking the liquid inside them can cause vomiting, pain, or even temporary paralysis. Only one type of barrel cactus contains drinkable water, and even that is a last resort. Here's how to access it: The only safe barrel cactus is the fishhook barrel cactus, located only in the southwest US and northwest Mexico. It's usually about 2 ft (0.6 m) in diameter, with long spines that end in a curve or hook. It may have red or yellow flowers at the top, or yellow fruit. It grows in drainages and on gravelly slopes. Cut off the top of the cactus with a machete, tire iron or other tool. Mash the white, watermelon-like interior into a pulp and squeeze out the liquid. Minimize the amount you drink. Even this fairly safe option tastes bitter and contains oxalic acid, which can cause kidney problems or bone pain.

Wrap plastic bags around plants. Shake the plant to reduce possible contaminants, then tie a plastic bag around it, sealing it shut around the stem. Weigh down the closed end of the bag with a rock to form a collection point for water to flow. Return at the end of the day to see if water has collected, due to the plant releasing vapor.

Test an unknown plant with extreme caution. If you have run out of options, you may need to search for fluid in plants you can't identify. Follow these precautions whenever possible: Test only one part of the plant at a time. Leaves, stem, roots, buds, and flowers may have different effects. Select a piece that produces fluid when you break it. Rule out plants with strong or acidic odors if you have other options. Do not eat for eight hours before the test. Touch the plant to the inside of your wrist or elbow to test for a reaction.

Comments

0 comment