views

X

Research source

Conceiving a Theory

Wonder "why?" Look for patterns between seemingly unrelated things. Explore the root causes behind everyday events, and try to predict what will happen next. If you already have the seed of a theory in your head, observe the subjects of that idea and try to gather as much information as possible. Write down the "hows," the "whys," and the links between causes and effects as you piece them together. If you don't have a theory or a hypothesis in mind, you can begin by making connections. If you walk through the world with a curious eye, you may be suddenly struck by an idea.

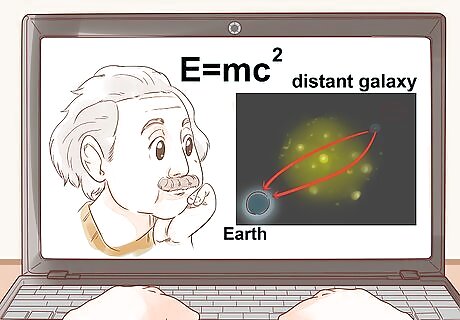

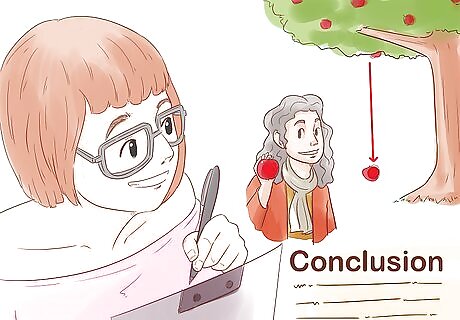

Develop a theory to explain a law. In general, a scientific law is the description of an observed phenomenon. It doesn't explain why the phenomenon exists or what causes it. The explanation of the phenomenon is called a scientific theory. It is a common misconception that theories turn into laws with enough research. For instance: Newton's Law of Gravity was the first to mathematically describe how two different bodies in the universe interact with each other. However, Newton’s law doesn’t explain why there is gravity, or how gravity works. It wasn’t until three centuries after Newton, when Albert Einstein developed his Theory of Relativity, that scientists began to understand how and why gravity works.

Research the academic precedents to your theory. Learn what has already been tested, proven, and refuted. Find out everything that you can about your subject, and determine whether anyone has asked the same questions before. Learn from the past so that you don't make the same mistakes. Use existing knowledge to better understand your subject. This includes equations, observations, and existing theories. If you are addressing a new phenomenon, try to build upon related theories that have already been proven. Find out whether anyone has already developed your theory. Before you go any further, try to make reasonably sure that no one else has already explored this topic. If you can't find anything, feel free to develop your theory. If someone has already made a similar theory, read through their work and see if you can build on it.

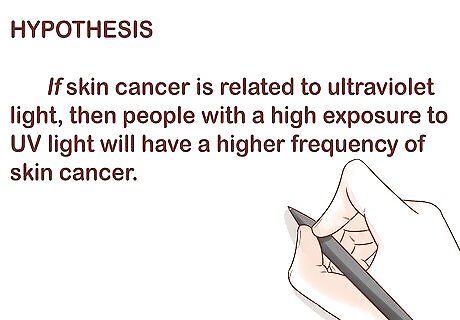

Build a hypothesis. A hypothesis is an educated guess or proposition that aims to explain a set of facts or natural phenomena. Propose a possible reality that follows logically from your observations – look for patterns, and think about what might cause those things to happen. Use an "if, then" form: "If [X] is true, then [Y] is true," or "If [X] is true, then [Y] is untrue." Formal hypotheses contain an "independent" and a "dependent" variable. The independent variable is a potential cause that you can tweak and control, while the dependent variable is a phenomenon that you observe or measure. If you are going to use the scientific method to develop your theory, then your hypothesis must be measurable. You cannot prove a theory without numbers to back it up. Try to come up with several hypotheses that might explain your observations. Compare these hypotheses. Consider where they overlap and where they split. Example hypothesis: "If skin cancer is related to ultraviolet light, then people with a high exposure to UV light will have a higher frequency of skin cancer." or "If leaf color change is related to temperature, then exposing plants to low temperatures will result in changes in leaf color."

Know that every theory starts as a hypothesis. Be careful not to confuse the two. A theory is a well-tested explanation for why a pattern exists, while a hypothesis is only a predicted reason for this pattern. A theory is always backed by evidence. A hypothesis, however, is only a suggested possible outcome, and it may or may not hold true.

Testing Hypotheses

Design an experiment. According to the scientific method, your theory must be testable. Develop a way to test whether each hypothesis holds true. Be sure to perform your test in a controlled environment: try to isolate the event and your proposed cause (the dependent and independent variable) from anything that might complicate the results. Be precise, and look out for external factors. Make sure that your experiments are repeatable. In most cases, it is not enough to simply prove a hypothesis once. Your peers should be able to recreate your experiment themselves and get the same results. Have peers or advisers review your testing procedure. Ask someone to look over your work and confirm that your logic is sound. If you are working with partners, make sure that everyone gives their input.

Find support. Depending on your field of study, it may be hard to run complex experiments without access to certain equipment and resources. Scientific gear can be expensive and tricky to procure. If you are enrolled in a university, speak with any professors and researchers who might be able to help. If you aren't in school, consider reaching out to professors or graduate students at a local university. For instance, contact the physics department if you want to explore a theory of physics. If you find a far-away university that is doing a lot of exciting research in your field, consider emailing them to ask about their research, their results, or their advice for your project.

Keep precise records. Again, experiments must be reproducible: other people must be able to set up a test in the same way that you did and get the same result. Keep accurate records of everything you do in your test. Be sure to keep all your data. If you're in academia, there are archives which store the raw data gathered in the process of scientific research. If other scientists need to find out about your experiment, they can consult these archives or ask you for your data. Make sure that you can provide all the details.

Evaluate the results. Compare your predictions against each other and against the outcomes of your experiments. Look for patterns. Ask yourself whether the results suggest anything new, and consider whether there's anything that you've forgotten. Whether or not the data confirms the hypothesis, look out for hidden or "exogenous" variables that may have influenced the results.

Establish certainty. If the results do not support your hypothesis, reject the prediction as incorrect. If you are able to prove the hypothesis, then the theory is one step closer to being confirmed. Always document your results with as much detail as possible. If a test procedure and its results cannot be reproduced, it will be much less useful. Make sure that the results do not change each time you do the experiment. Repeat the tests until you're sure. Many theories get abandoned after being refuted by experiment. However, if your new theory explains something that previous theories can't, it may be an important scientific advance.

Accepting and Expanding a Theory

Draw a conclusion. Determine whether your theory is valid, and make sure that your experimental results are repeatable. If you accept the theory, you should not be able to disprove it with the tools and information at your disposal. Do not, however, try to spin your theory into absolute fact.

Share your results. You will likely amass a lot of information in your quest to prove your theory. When you are confident that your results are repeatable and your conclusions are valid, try to distill your theory into a paper others can study and understand. Lay out your process in a logical order: first, write an "abstract" that summarizes your theory; then, lay forth your hypothesis, your experimental procedure, and your results. Try to distill your theory into a series of points or arguments. Finally, end the paper with an explanation of your conclusions. Explain how you defined your question, the approach you took, and how you tested it. A proper report will walk the reader through every relevant thought and action that brought you to your conclusion. Consider your audience. If you want to share your theory with peers in your field, write an formal paper explaining your results. Consider submitting your work to an academic journal. If you want to make your findings accessible to the general public, try distilling your theory into something more digestible: a book, an article, or a video.

Understand the peer-review process. In the scientific community, theories are not generally considered valid until they have been peer-reviewed. If you submit your findings to an academic journal, another scientist may decide to peer-review—that is to say, test, consider, and replicate—the theory and process that you have put forward. This will either confirm the theory or leave it in limbo. If the theory survives the test of time, others may eventually try to expand your idea by applying it to other subjects.

Build upon your theory. Your thought process does not need to end after you share your theory. Indeed, you may find that the act of writing up your ideas forces you to consider factors that you've been ignoring. Don't be afraid to keep testing and revising your theory until you're completely satisfied. This may mean more research, more experiments, and more papers. If your theory is large enough in scope, you may not ever be able to flesh out the implications in their entirety. Don't be afraid to collaborate. It can be tempting to keep your intellectual sovereignty, but you may find that your ideas take on new life when you share them with peers, friends, and advisers.

Comments

0 comment