views

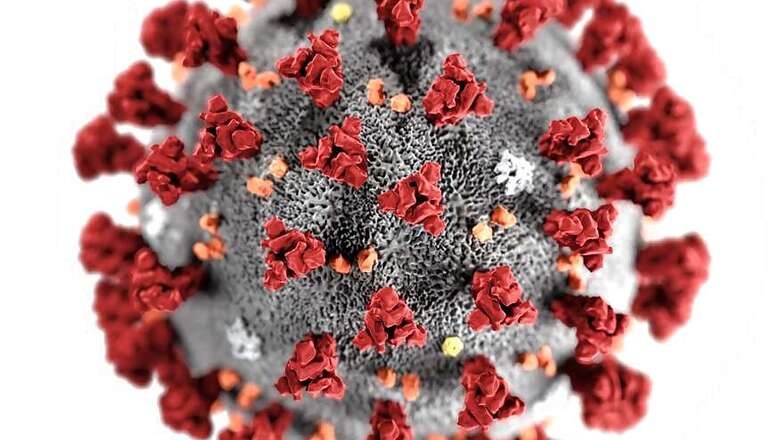

Are the Chinese citizens angry with their government’s initial denials and the subsequent handling of the Coronavirus outbreak? Yes, they are. Or maybe they aren’t. There really is no way to tell. Or is there? It turns out that China’s social media users have created a new language to somehow beat government’s censorship on Coronavirus, or COVID-19, chatter. No one really knows that the government is censoring and when or for what reason. Or what conversations the cyber cops may be busy scrubbing off social media and the internet. A research by Amnesty International has pointed out how the social media users in China are self-censoring and modifying the words they use, to beat the surveillance on their chats. Now it will be Pandas and Noodles and the Truth, across social networks and messengers in China—if you don’t want to be in trouble.

The research suggests that people are using the abbreviation “zf” to refer to the government, “jc” to refer to the police, “guobao” (which means "national treasure") or panda images to represent the domestic security bureau and mentions of the Communist Party’s Publicity Department (also known as the Propaganda Department) are referenced as “Ministry of Truth” from the George Orwell novel “1984”. Chinese citizens are using “wh” and “hb” to refer to Wuhan and Hubei.

Have you read?

WeChat is Censoring Coronavirus Keywords, Because China Doesn’t Like Bad Press?

China Has Made Spreading Rumours on Social Media A Crime as it Battles The Coronavirus Outbreak

“Since China’s National Red Cross and its ability to distribute supplies has been questioned, netizens anticipated ‘Red Cross’ would be censored and replaced it with “red ten” (the Chinese character for ten “十 Shí” resembles a cross). When people express suspicions that supplies had been mishandled by the national Red Cross society, hashtags such as “supplies are reded” began trending,” says Amnesty.

Any critical references to the politicans in China aren’t taken very kindly to. The research suggests that social media users in the country are reviving the abbreviation “F4”. It started out as a Taiwanese boy band which became incredibly popular in the early 2000s, but is now used to refer to four regional politicians—the governor of Hubei province, the secretary of Hubei’s Communist Party Committee, the mayor of Wuhan and the party secretary of Wuhan. Most of the responsibility for the botched response to the Coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan rests on the shoulders of these four political figures.

In case you were wondering, “Vietnamese pho noodles” is used to refer to VPNs, methods that are essential to access websites otherwise blocked by the Great Chinese Firewall.

And it does get absurd at some stage, as one would expect. “Similarly, a parent’s complaint on Weibo about his child being “bad at learning” was instantly removed. Why? Because in Chinese, the President’s surname means “learning”. In this context, to say “learning is bad” must be censored,” say the researchers.

Earlier this month, a Citizen Lab report had revealed that popular instant messaging app WeChat is censoring certain keywords, particularly any references of the Coronavirus, COVID-19, Wuhan, President Xi Jinping or Dr. Li Wenliang who had blown the lid off the outbreak much before the Chinese government had to accept what happened. “Between January 1 and February 15, 2020, we found 516 keyword combinations directly related to COVID-19 that were censored in our scripted WeChat group chat. The scope of keyword censorship on WeChat expanded in February 2020. Between January 1 and 31, 2020, 132 keyword combinations were found censored in WeChat. Three hundred and eight-four new keywords were identified in a two-week testing window between February 1 and 15,” the researchers say.

The alternate language and a new social media dictionary might be enabling messaging across the country, where freedom of speech isn’t exactly a priority. But it is also time consuming, and the energies would be better channelized elsewhere if the struggle for freedom of speech wasn’t there.

This month, the new cyberspace regulations went Live in China in the midst of the measures to contain the Coronavirus, or COVID-19 outbreak. Among the long list of do’s and don’ts released by the Cyberspace Administration of China in the Regulations on the Ecological Governance of Network Information Content, one guideline that truly stands out is the one that reads “spreading rumors and disturbing the economic and social order” under Article 6 which headlines Producers of online information content may not produce, copy or publish illegal information containing the following contents”.

One would suspect it is only a matter of time perhaps before this language will need updating.

Comments

0 comment