views

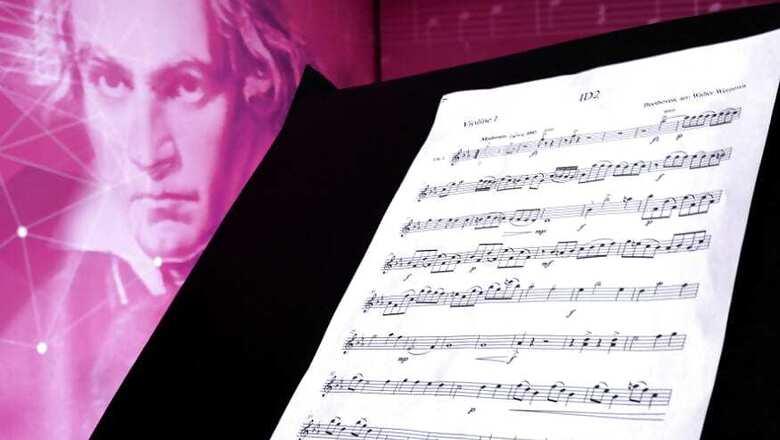

A few notes scribbled in his notebook are all that German composer Ludwig van Beethoven left of his Tenth Symphony before his death in 1827. Now, a team of musicologists and programmers is racing to complete a version of the piece using artificial intelligence, ahead of the 250th anniversary of his birth next year. "The progress has been impressive, even if the computer still has a lot to learn," said Christine Siegert, head of archives at Beethoven House in the composer's hometown of Bonn.

Siegert said she was "convinced" that Beethoven would have approved since he too was an innovator at the time, citing his compositions for the panharmonicon -- a type of organ that reproduces the sounds of wind and percussion instruments. And she insisted the work would not affect his legacy because it would never be regarded as part of his oeuvre. The final result of the project will be performed by a full orchestra on April 28 next year in Bonn, a centrepiece of celebrations for a composer who defined the romantic era of classical music.

"It's completely new territory," said Dirk Kaftan, conductor of the Beethoven Orchestra, which will perform the piece. "We musicians are in two minds about it." Beethoven, Germany's most famous musical figure, is loved in his homeland and critics of the project are concerned about protecting Beethoven's legacy. The "national duty" to prepare for the anniversary was even written into a right-left coalition agreement to form a govenment six years ago. The year of celebrations officially begins on December 16 -- believed to be his 249th birthday.

But a press preview on Friday at the Beethoven House Museum in his native Bonn following a renovation offered insights into his genius, including the notebooks he used to communicate after going deaf in 1801 -- 26 years before his death.

Scope for improvement

Beethoven began working on the Tenth Symphony alongside his Ninth, which includes the world-famous "Ode To Joy". But he quickly gave up on the Tenth, leaving only a few notes and drafts by the time he died aged 57. In the project, machine-learning software has been fed all of Beethoven's work and is now composing possible continuations of the symphony in the composer's style. Deutsche Telekom, which is sponsoring the project, hopes to use the findings to develop technology such as voice recognition.

The team said the first results a few months ago were seen as too mechanical and repetitive but the latest AI compositions have been more promising. Barry Cooper, a British composer and musicologist who himself wrote a hypothetical first movement for the Tenth Symphony in 1988, was more doubtful. "I listened to a short excerpt that has been created. It did not sound remotely like a convincing reconstruction of what Beethoven intended," said Cooper, a professor at the University of Manchester and the author of several works on Beethoven.

"There is, however, scope for improvement with further work." Cooper warned that "in any performance of Beethoven's music, there is a risk of distorting his intentions" but this was particularly the case for the Tenth Symphony as the German composer had left only fragmentary material. Similar AI experiments based on works by Bach, Mahler and Schubert have been less than impressive. A project earlier this year to complete Schubert's Eighth Symphony was seen by some reviewers as being closer to an American film soundtrack than the Austrian composer's work.

Comments

0 comment