views

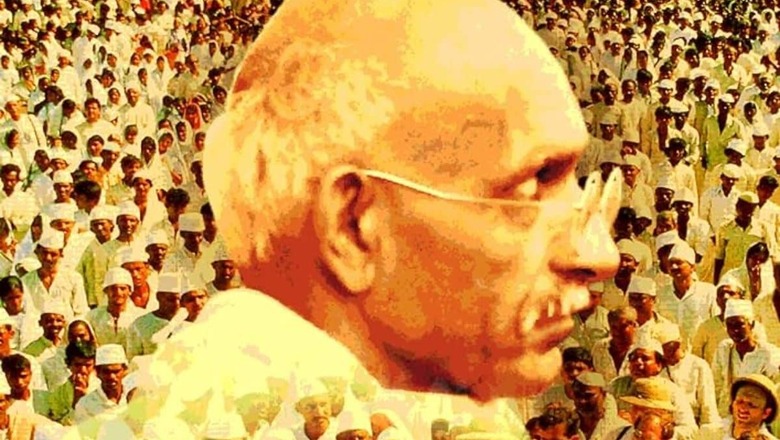

Sir Richard Attenborough, the producer and director of the movie ‘Gandhi’ (released in 1982), once reminisced in an article that Naseeruddin Shah was one of the most recommended names for the role of Mahatma Gandhi or Bapu, as we Indians call him. However, the role ultimately went to British star Ben Kingsley, who won the Academy Award for Best Actor. Kingsley, born in Scarborough, Yorkshire, England, is of English and Indian descent, and his original name is Krishna Bhanji.

The movie, since its release, has become a historical visual epic saga. It was nominated in 11 categories at the Academy Awards and won eight awards, including Best Picture, Best Direction, and Best Writing. Made on a budget of $22 million, the movie was a commercial success and highly appreciated for its accurate portrayal of Bapu’s life and the journey of the Indian freedom struggle.

The movie ‘Gandhi’ is one of the prized possessions not only of world cinema, but also of the world’s recorded history. It is a “must-have” experience for anyone who values the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and takes pride in having his works as collectibles.

Its narrative summary is unique, and although many critics say it tried to deify Bapu, it presents a period biography in a manner that does justice to Gandhian thoughts and the life and evolution of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Despite having an ensemble cast and thousands of extras (earning a record in the Guinness Book — 300,000 extras in Bapu’s funeral scene), the movie meticulously addresses every character portrayal, from Muhammad Ali Jinnah to Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, and others. Whether with limited screen time or recurring appearances, the narrative related to every character is a paragraph of the Indian freedom struggle.

Much has been written about the Mahatma, and much continues to be written. Many movies have been made and are still being made about him, his views, his lifeand the role of non-violence. His teachings and views have been translated into many languages in India and around the world.

Seventy-five years after his death, he continues to inspire the world, whether in South Africa, where he began his journey to becoming the Mahatma who liberated India from colonial slavery, or in the United States, the world’s most powerful democracy, or in the United Kingdom, the colonial ruler over India. The Gandhian thought of non-violence remains a significant political ideology not only in India, but also in many countries around the world.

Richard Attenborough’s ‘Gandhi’ beautifully captures all these facets for global audiences.

The movie has been and continues to be one of the gateways to introduce the Mahatma to newer generations and the global community who may still be unaware of him, but want to learn about him. In an OTT-dominated world, where cinema is one of the most potent forms of visual communication, ‘Gandhi’ remains relevant and cherished. This India-Britain joint venture has been loved globally since its release, and with a more connected digital world now and in the future, it will always be a historical visual book to revisit the Gandhian text.

The film is an example of craftsmanship by a master storyteller. Every shot is an integral part, as if the movie could not have been made without it. Every frame is meticulously composed. You can study the use of lighting, camera angles, costume design, sets, locales and props, all supporting the characters in each frame, complemented by brilliant background music. The movie won Academy Awards for Art Direction, Cinematography, and Costume Design.

Two aspects stand out, which had the most direct impact on making the movie a masterpiece.

One is the use of specific incidents from almost four decades of Mahatma’s life in India after his return from South Africa. Four decades is a long period and considering that India’s freedom struggle had become synonymous with the Mahatma, it was a challenging task to create a concise three-hour narrative. The movie accomplishes this with such craftsmanship that the audience never feels disoriented when the movie transitions from one frame to another, even if the events are years apart. The moving images maintain artistic expression consistency and relevance in content selection.

The other significant aspect is the way characters convey the visual language. Frame after frame, the movie is a visual book, portraying Bapu’s life, and the maturation of the Indian freedom struggle under his leadership, culminating on August 15, 1947.

The film begins with Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination and funeral, then goes backward to capture human emotions as the story progresses — a singular point in any visual creativity. The body language of the characters runs parallel to the story’s flow, with everyone playing their roles perfectly, but Kingsley mesmerises.

Bapu’s initial years as a young lawyer in South Africa, his first steps towards becoming the man the world later recognises, begin in a South African train’s first-class compartment in 1893, where he was expelled despite holding a first-class ticket due to being an Indian. His actions forced the British to abolish anti-Indian laws in South Africa. His journey back to India in 1915, clad in Indian attire that a foreigner described as coolie-like, is authentically portrayed frame by frame.

In India, Bapu started as a quintessential common Indian who was unsure about what to do next because he knew little about the country. With advice from Gopal Krishna Gokhale, he decided to travel to different parts of India, in a third-class railway compartment.

Subsequently, he appeared at an Indian National Congress’s open public meeting. Uncertain about what to say, he ended up addressing what was missing in the Indian freedom struggle. Bapu posed valid questions that challenged the way the freedom movement was conducted in India, mainly confined to major cities like Mumbai and Delhi, led by lawyers, while 700,000 villages, which Bapu considered “real India”, remained oblivious, their political concerns limited to necessities of bread and salt. His initial message for the freedom movement was to connect with this “real India” first. The subsequent scenes leading to the movie’s climax follow similar patterns.

Symbolism and leitmotifs are plentiful in the movie. The docudrama style, with silent frames and characters interspersed throughout the narrative, adds gravitas.

Bapu’s path to non-violence, which began in South Africa, is a recurring theme in the movie, depicted through India’s freedom struggle from 1915 to 1948, the period of his life in India. Whether it’s the Non-Cooperation Movement of 1920-22, the Salt March of 1930, the Quit India Movement of 1942, or the fasts of 1947 to quell communal violence, the movie ‘Gandhi’ consistently highlights this theme.

The movie ‘Gandhi’ is a “must-watch” multiple times for anyone who believes in Bapu’s ideology and the transcendental power of meaningful cinema.

The movie ‘Gandhi’ is not just a cinematic journey; it is also a visual history book.

Comments

0 comment