views

In the movie Godfather 2, Michael Corleone says, “Keep your friends close, your enemies closer.”

Apply that to contemporary geopolitics. India is surrounded by both friends and enemies. Complicating matters is a category Don Corleone hadn’t thought of— frenemies.

Fluctuating ties over the years

The United States is an old friend but an older frenemy. During India’s freedom movement, the US was a steadfast friend. US President Franklin Roosevelt lectured British Prime Minister Winston Churchill on the contradiction of fighting Nazi fascism in Germany while practising colonial fascism in India.

After Independence, America remained a friend but drifted apart from India as India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru leant towards the Soviet Union, followed socialist economic policies, and became a founder of the non-aligned movement (NAM).

By the 1970s, Washington under Nixon-Kissinger had turned into a frenemy, tilting towards Pakistan in the Bangladesh war and trying to intimidate India by sending the Seventh Fleet into the Bay of Bengal.

India and America restored the relationship after Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s successful visit to Washington in 1985. The friendship solidified in the 2000s under the George W Bush administration following the India-US nuclear deal.

The US regarded India as a strong but not mission-critical ally. The rise of China over the past ten years changed the dynamic.

In the parabolic arc from the Middle East to the South China Sea, only India provided the US with the geostrategic depth to counter China in the Indo-Pacific.

However, a problem arises in a relationship when one partner seeks equality with the other dominant partner. That is what we saw playing out in the kerfuffle between Washington and New Delhi over India’s internal politics.

State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller had two options when a Bangladeshi journalist with ties to George Soros-funded NGOs asked him about the US position on Arvind Kejriwal’s arrest. He could have said the US does not comment on the internal affairs of other sovereign nations.

Instead, he said: “We continue to follow these actions closely, including the arrest of Arvind Kejriwal. We encourage fair, transparent and timely legal processes for each of these issues.”

India’s response was unusually curt. The ministry of external affairs (MEA) under minister S Jaishankar does not mince words these days. It told the US to mind its own business. It had said the same to Germany the day before.

To make sure the message was understood, a senior diplomat from the US embassy was summoned to the MEA and given a polite dressing down.

After a further back-and-forth between the US State Department, a United Nations spokesperson, and a strong rebuttal by India’s Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar, the matter settled down.

Indispensable India?

For neo-con elements in the Joe Biden administration, India’s geostrategic importance as a counterweight to China is a source of occasional frustration. Washington likes obedient allies. It does not care too much for those who follow an independent geopolitical path as India does.

And yet, Washington is practical. It knows it has to live with a rising India in the long term. It knows that India will be the world’s third-largest economy by 2028. Grin and bear it, say Biden’s advisors.

For India, China poses a more serious concern. It is obviously neither a friend nor a frenemy — just simply an enemy. But cracks in its hostility to India are showing. At a recent media event, a senior Chinese embassy diplomat asked the audience to “visit China and experience Chinese friendship”.

Beijing has watched with interest the terse exchange between Delhi and Washington over Kejriwal’s arrest and the Congress’s tax notices. China’s President Xi Jinping tried hard between 2014 and 2019 to wean India away from the US geopolitical orbit. Three summits between Xi and Modi in Ahmedabad, Wuhan, and Mahabalipuram during these five years failed to dilute India’s strategic partnership with the US.

The four-year-long standoff from April 2020 in east Ladakh, months after the Mahabalipuram summit, is an expression of Chinese anger at its failure to stall the India-US strategic partnership.

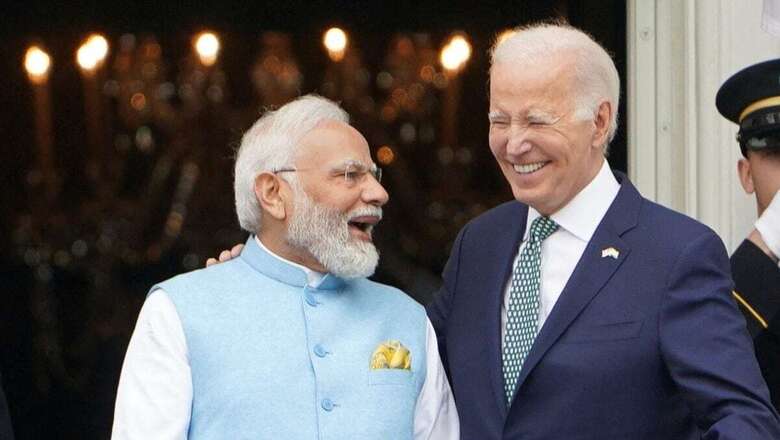

Washington was pleased with this outcome. It gave Modi a state reception in June 2023 and helped make India’s G20 presidency a success.

But even as Biden travelled to New Delhi for the G20 Summit in September 2023, tensions had begun to build in the relationship.

The murder-for-hire allegations against fugitives in Canada and the US were only a ruse. The problem is America likes to be in absolute control of its strategic partnerships. In NATO, with its European allies, it has the last word. In East Asia, with its Japanese and Korean allies, it calls the shots. In West Asia, with its Gulf Arab allies, America is the unquestioned leader.

India is more complicated. For the first time in decades, it is an ally that the US needs at least as much as the ally needs the US.

America’s paranoia over a strengthening China-Russia-Iran-North Korea axis makes it imperative to have a strong, dependable ally in the region. Only India fits the bill.

That’s not a situation Washington is entirely comfortable with. To keep India just a little off-balance it uses its embedded media and assorted NGOs to ask questions about religious freedom and democracy in India.

Western agencies like Freedom House are commandeered to amplify the message to New Delhi: know your place.

Unfortunately for Washington, that ship has sailed. India knows who its friends, enemies, and frenemies are.

Each receives the geostrategic proximity — or distance — India’s national interest demands.

The writer is an editor, author and publisher. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment