views

With the aid of a small crane, Borja Saracho lowers five cages loaded with 2,500 bottles of white wine from a fishing boat into the Cantabrian Sea. He then plunges into the sea wearing a wetsuit to check sensors that monitor temperature and water pressure around the precious load. "We are a winery," says the 44-year-old founder of Crusoe Treasure in the picturesque bay of Plentzia near Bilbao in Spain's northern Basque region.

Until several years ago this diving enthusiast did not even drink wine. Now he sells wines that have been aged underwater -- a growing niche market -- in Spain as well as in Belgium, China, Switzerland, Germany and Japan. "I have always been interested in sunken ships and hidden treasures," said Saracho, whose company has been in the market since 2013 and is the largest underwater winery in Spain.

Crusoe Treasure expects to sell 30,000 bottles of red and white wine this year, up from just 7,000 in 2017. The prices of its wines start at 58 euros ($67.50) a bottle. It is one of about a dozen firms that age wines underwater in Spain. Other firms which age wine underwater exist in Italy, France and Chile. The underwater conditions -- total darkness and constant temperature -- are thought to accelerate the ageing process, adding complexity to the wine.

But it comes at a price -- the technique costs 25-70 percent more for the winemaker than ageing wine on land because of the logistics required. Entrepreneurs are investing in this sector "thinking it is not a fad, but a technique that in the medium term can be very useful" and "add qualities to a wine that make it more attractive to the public," said Rafael del Rey, the director of the Spanish Wine Market Observatory, an independent foundation.

Ageing wine under the sea, with its tides, currents and waves, can be "very rough" so it is best to work with "very robust wines", said Crusoe Treasure's chief oenologist, Antonio Palacios.

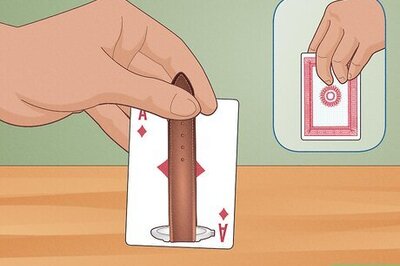

The company works with wineries from different parts of Spain, and since it is not restricted by the system of geographical indications, or designation of origin protection linked to where a wine is produced, it can mix different strains of grapes from more than one region. Most of the wines are stored first in barrels of the firm's partner wineries before they are transferred to bottles, which are closed with a special stopper and seal.

The bottles then go 20 metres (65 feet) under the sea, where they rest for six to 12 months in metal cages. Over in the northeastern region of Catalonia, the Hotel Cala Joncols has since 2009 aged wines underwater. It keeps them only six months underwater because "any longer and wine can lose its edge", said its sommelier Josep Lluis Vilarasau.

The hotel uses young and recently bottled wines which they store 17 metres underwater.

One of its wines sells for 30 euros a bottle for the traditional earth produced version and 40 euros if it was underwater. They even sell a white wine which they produce from beginning to end using a grape grown on a parcel of land beside the hotel. The philosophy is to dispense with woody aromas and preserve "those primary aromas which are of fruit, flowers and minerals," said Vilarasau.

The result is a wine which has "more intense and brighter colours" and "greater volume, greater freshness", he added.

Wines are also aged underwater off the coast of the northwestern region of Galicia, where each year the Raul Perez Vineyards produce 1,200 bottles of Albarino, a zesty local wine which is excellent with fish and seafood. Two other firms will soon join the market: Undersea, based in the southeastern region of Murcia, which wants to start with a yearly production of between 50,000 and 60,000 bottles, and Bodega Palmera Castro y Magan, which currently produces wines in La Palma, one of Spain's Canary Islands.

Maria Nancy Castro Rodriguez, owner of Bodega Palmera Castro y Magan, underlines this niche is still at a pioneering stage. "There is little information, no bibliography, no analytical basis nor practice," she said. Wines aged underwater are still largely unknown and hard to find in restaurants and shops. "We would like there to be more awareness of the concept of underwater wine on the part of consumers and professionals," said Palacios.

Vilarasau, the sommelier, hopes underwater wines will follow the lead of natural wines -- made without any chemical additives -- which took off over the last decade. "They are fashions which at first cost, but if the public tries and accepts the product, and likes it, it grows and takes shape," he said.

Comments

0 comment