views

"Kapil Sibal is an idiot" proclaimed innumerable updates on Facebook and Twitter in response to the government's efforts to get social networking websites to pre-screen content posted by users. The question isn't whether the IT minister is an idiot or not but why are governments so afraid of the social network?

It is not only the Government of India (and other democratic and not-so-democratic countries) but also big corporates who shudder at the very thought of the viral power that the new age modes of communication put on the fingertips of an otherwise nondescript Internet user.

Social networking isn't a 2011 phenomenon. It has been around and accelerating since the last decade. What makes social networking stand out in 2011 is that it has not only been an agent of change but has also empowered its users in ways like never before.

The Indian government has been accused of trying to force Internet companies to pre-screen content in view of the online leverage that the anti-corruption movement spearheaded by Anna Hazare has garnered. The government denied the assertions, but the suspicion lingers.

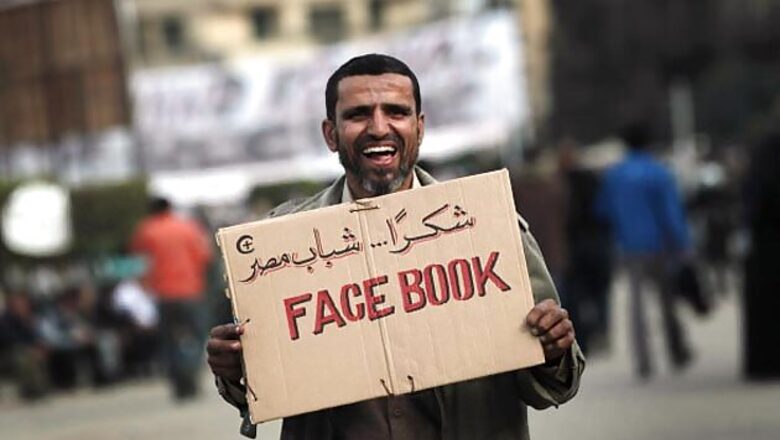

The role of the new age Internet communication in the Arab Spring has been widely discussed and documented. This information revolution can and has undermined authority and empowered individuals and groups to spread dissent to alter the traditional political power structures.

The rise of the smartphones, the highlight of the mobile phone market in 2011, is making sharing on social networks more impulsive and immediate. This instancy is the biggest pull for some social networking services and also the biggest temptation for the authorities to step in to stem the 'undesirable' information flow.

There are many ways in which governments have been attempting to tackle this new-age threat. One is the China model - block whatever you don't want citizens to access. The second is the Russia model where websites of dissident bloggers regularly attacked by hackers believed to be sympathetic to the Kremlin. The third is what western democracies, such as the US, have been surreptitiously doing - target, track, analyse and use. CIA has a secret facility in Virginia where a team of experts track Twitter, Facebook, Internet chat rooms and the traditional media for information on, amongst other things, brewing unrest.

The US has been at the receiving end of the Occupy Wall Street protests organised though social media. Washington is now actively training officials on how to use the social media in the government's interests. As an early adopter in the matters of online communication, the US State Department advising other governments on social media.

There are also reports of the US military developing software to make it possible for government agencies to clandestinely manipulate social websites to spread propaganda. During the UK riots, British Prime Minister David Cameron flirted with the idea of social media censorship and invited widespread criticism.

Even strict government control over what is expressed online could not prevent scathing criticism of the Chinese government by online Chinese after a high-speed rail crash.

Hosni Mubarak attempted to shut down the Internet in Egypt and Google (with support from Twitter) responded by launching a workaround that allowed people in Egypt to post Twitter updates by dialling a phone number and leaving a voicemail.

Status updates by millions cannot by themselves force change but they have become one of the most potent tools around to gather support for on-the-ground activity.

With everyone having an almost equal opportunity to be heard in the online word malicious rumours also spread fast. This is what governments, such as that of India, say they want to control. Irreverence is one of the attributes of a large part of the online population.

Fake reports of celebrity deaths, including that of former Indian President APJ Abdul Kalam, regularly trend on Twitter.

While other users actively help in policing such content, sometimes damage is done before the more responsible users are able to initiate a clean-up effort.

The law in many countries is also taking irresponsible social media updates very seriously. Two Mexicans face possible 30-year sentences for terrorism and sabotage for posting tweets that caused in panic amongst residents resulting in clogging of emergency numbers.

Incautious and malicious use of social networking services cannot override the benefits. When serial bomb blasts targeted Mumbai on July 13 this year, resilient and resourceful citizens of the Maximum City logged online to extend a helping hand to each other. Twitter and Facebook was flooded with posts from people offering a ride, food, overnight stay for stranded people and blood donation. And this was not the first instance of social networks coming to the rescue in the time of crisis.

A scroll through @twitterstories and Facebook Stories brings out many positive stories that the social networks helped create.

All of this also highlights the immense power that we as users have handed over to the major social media companies to become the gatekeepers of dissent and debate. A few Internet companies are now able to effectively control, if they wish to, what is being said and shared around the world.

Also incidents of unauthorised access into what were believed to be secure systems have also raised fears of hackers being able to sneak into communication streams reveal the perils of a networked world.

Such fears should not be a deterrent for citizens to make the best out of the available resources.

Social networks have also forced a change in the traditional top-down news flow structure. Many incidents are not broken by mainstream media outlets but often by an innocuous status update from someone who just happened to be at the venue.

33-year-old Sohaib Athar unwittingly live tweeted the raid that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden and became an overnight celebrity with journalists from across the world trying to get in touch with him for his account of the event.

The next day news organisations were vexed with doctored photos purporting to show a dead Osama bin Laden that went viral on social networking websites. Some media organisations even published the image that was later found to be a morphed version of a Reuters photo of the world's most wanted terrorist.

Sharp-eyed consumers of news content keep journalists on their toes not hesitating to point out, and letting the world know of, inadvertent or intended errors.

Even governments are now reaching out to citizens on social networks on important issues such as the redraft of the constitution. In tech-savvy Iceland where two-thirds of Icelanders are on Facebook, the council drafting the new constitution invited inputs from citizens via Facebook and Twitter, YouTube and Flickr.

Big businesses can now no longer depend on an advertising blitzkrieg for sales and image building. They now need to keep an ear (and an eye) on what is being said by people online and think of strategies to undo the damage.

An otherwise faceless customer now has a voice thanks to the social network, louder than ever before, to let his grievances against a company known to the wider world. Big corporates are often left scurrying for cover in the face of a social media onslaught. Businesses can no longer take customers for granted, those who do, do it at the cost of their online image.

The numbers are also accelerating. Facebook now has over 800 million active users, Twitter has over 100 million and the recent arrival Google+ has quickly added 60 million. The social network is already said to be the third most populous 'country' in the world. A country of such vocal and networked individuals is easily a superpower.

The year 2011 will stand out as the year when the power was handed back to the people, rather snatched, by the aam aadmi of the world wielding their social network profiles.

Social media could very well be the best thing to happen to democracy since universal adult franchise.

####

Comments

0 comment