views

How to Lay the Groundwork

Read the prompt carefully. In most cases, you will be given a specific assignment for your persuasive essay. It’s important to read the prompt carefully and thoroughly. Look for language that gives you a clue as to whether you are writing a purely persuasive or an argumentative essay. For example, if the prompt uses words like “personal experience” or “personal observations,” you know that these things can be used to support your argument. On the other hand, words like “defend” or “argue” suggest that you should be writing an argumentative essay, which may require more formal, less personal evidence. If you aren’t sure about what you’re supposed to write, ask your instructor.

Give yourself time. If you can, make the time to craft an argument you'll enjoy writing. A rushed essay isn’t likely to persuade anyone. Allow yourself enough time to brainstorm, write, and edit. Whenever possible, start early. This way, even if you have emergencies like a computer meltdown, you’ve given yourself enough time to complete your essay.

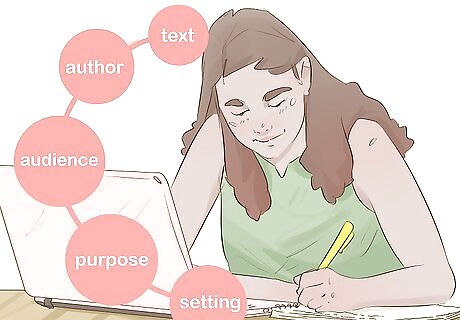

Examine the rhetorical situation. All writing has a rhetorical situation, which has five basic elements: the text (here, your essay), the author (you), the audience, the purpose of the communication, and the setting. Try using stasis theory to help you examine the rhetorical situation. This is when you look at the facts, definition (meaning of the issue or the nature of it), quality (the level of seriousness of the issue), and policy (plan of action for the issue). To look at the facts, try asking: What happened? What are the known facts? How did this issue begin? What can people do to change the situation? To look at the definition, ask: What is the nature of this issue or problem? What type of problem is this? What category or class would this problem fit into best? To examine the quality, ask: Who is affected by this problem? How serious is it? What might happen if it is not resolved? To examine the policy, ask: Should someone take action? Who should do something and what should they do?

Consider your audience. What’s persuasive to one person may not be persuasive to another. For this reason, it’s crucial to consider to whom you are targeting your essay. Obviously, your instructor is your primary audience, but consider who else might find your argument convincing. For example, if you are arguing against unhealthy school lunches, you might take very different approaches depending on whom you want to convince. You might target the school administrators, in which case you could make a case about student productivity and healthy food. If you targeted students’ parents, you might make a case about their children’s health and the potential costs of healthcare to treat conditions caused by unhealthy food. And if you were to consider a “grassroots” movement among your fellow students, you’d probably make appeals based on personal preferences.

Pick a topic that appeals to you. Because a persuasive essay often relies heavily on emotional appeals, you should choose to write on something about which you have a real opinion. Pick a subject about which you feel strongly and can argue convincingly.

Look for a topic that has a lot of depth or complexity. You may feel incredibly passionate about pizza, but it may be difficult to write an interesting essay on it. A subject that you're interested in but which has a lot of depth — like animal cruelty or government earmarking — will make for better subject material.

Consider opposing viewpoints when thinking about your essay. If you think it will be hard to come up with arguments against your topic, your opinion might not be controversial enough to make it into a persuasive essay. On the other hand, if there are too many arguments against your opinion that will be hard to debunk, you might choose a topic that is easier to refute.

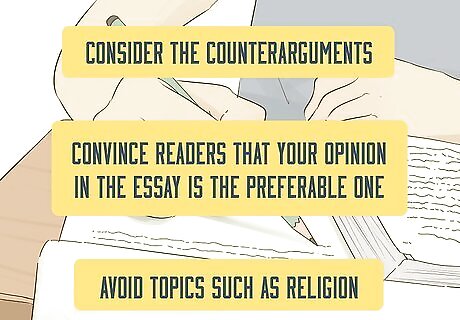

Make sure you can remain balanced. A good persuasive essay will consider the counterarguments and find ways to convince readers that the opinion presented in your essay is the preferable one. Make sure you choose a topic about which you’re prepared to thoroughly, fairly consider counterarguments. (For this reason, topics such as religion usually aren’t a good idea for persuasive essays, because you’re incredibly unlikely to persuade someone away from their own religious beliefs.)

Keep your focus manageable. Your essay is likely to be fairly short; it may be 5 paragraphs or several pages, but you need to keep a narrow focus so that you can adequately explore your topic. For example, an essay that attempts to persuade your readers that war is wrong is unlikely to be successful, because that topic is huge. Choosing a smaller bit of that topic -- for example, that drone strikes are wrong -- will give you more time to delve deeply into your evidence.

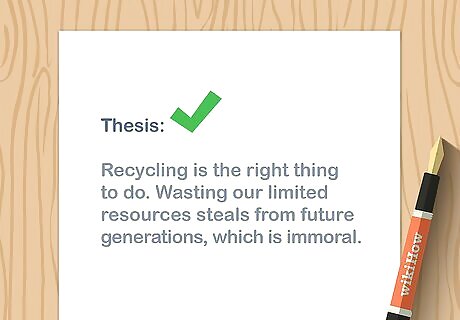

Come up with a thesis statement. Your thesis statement presents your opinion or argument in clear language. It is usually placed at the end of the introductory paragraph. For a persuasive essay, it’s especially important that you present your argument in clear language that lets your readers know exactly what to expect. It also should present the organization of your essay. Don’t list your points in one order and then discuss them in a different order. For example, a thesis statement could look like this: “Although pre-prepared and highly processed foods are cheap, they aren’t good for students. It is important for schools to provide fresh, healthy meals to students, even when they cost more. Healthy school lunches can make a huge difference in students’ lives, and not offering healthy lunches fails students.” Note that this thesis statement isn’t a three-prong thesis. You don’t have to state every sub-point you will make in your thesis (unless your prompt or assignment says to). You do need to convey exactly what you will argue.

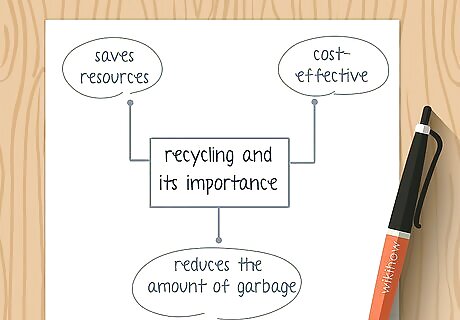

Brainstorm your evidence. Once you have chosen your topic, do as much preparation as you can before you write your essay. This means you need to examine why you have your opinion and what evidence you find most compelling. Here’s also where you look for counterarguments that could refute your point. A mind map could be helpful. Start with your central topic and draw a box around it. Then, arrange other ideas you think of in smaller bubbles around it. Connect the bubbles to reveal patterns and identify how ideas relate. Don’t worry about having fully fleshed-out ideas at this stage. Generating ideas is the most important step here.

Research, if necessary. Once you have your ideas together, you may discover that some of them need research to support them. Doing your research before you begin “writing” your essay will make the writing process go smoothly. For example, if you’re arguing for healthier school lunches, you could make a point that fresh, natural food tastes better. This is a personal opinion and doesn’t need research to support it. However, if you wanted to argue that fresh food has more vitamins and nutrients than processed food, you’d need a reliable source to support that claim. If you have a librarian available, consult with him or her! Librarians are an excellent resource to help guide you to credible research.

How to Draft Your Essay

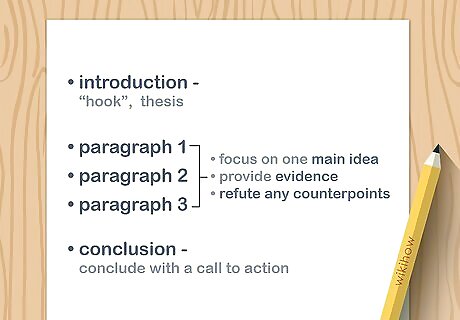

Outline your essay. Persuasive essays generally have a very clear format, which helps you present your argument in a clear and compelling way. Here are the elements of persuasive essays: An introduction. You should present a “hook” here that grabs your audience’s attention. You should also provide your thesis statement, which is a clear statement of what you will argue or attempt to convince the reader of. Body paragraphs. In 5-paragraph essays, you’ll have 3 body paragraphs. In other essays, you can have as many paragraphs as you need to make your argument. Regardless of their number, each body paragraph needs to focus on one main idea and provide evidence to support it. These paragraphs are also where you refute any counterpoints that you’ve discovered. Conclusion. Your conclusion is where you tie it all together. It can include an appeal to emotions, reiterate the most compelling evidence, or expand the relevance of your initial idea to a broader context. Because your purpose is to persuade your readers to do/think something, end with a call to action. Connect your focused topic to the broader world.

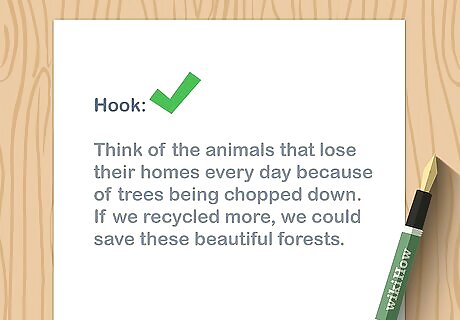

Come up with your hook. Your hook is a first sentence that draws the reader in. Your hook can be a question or a quotation, a fact or an anecdote, a definition or a humorous sketch. As long as it makes the reader want to continue reading, or sets the stage, you've done your job. For example, you could start an essay on the necessity of pursuing alternative energy sources like this: “Imagine a world without polar bears.” This is a vivid statement that draws on something that many readers are familiar with and enjoy (polar bears). It also encourages the reader to continue reading to learn why they should imagine this world. You may find that you don’t immediately have a hook. Don’t get stuck on this step! You can always press on and come back to it after you’ve drafted your essay.

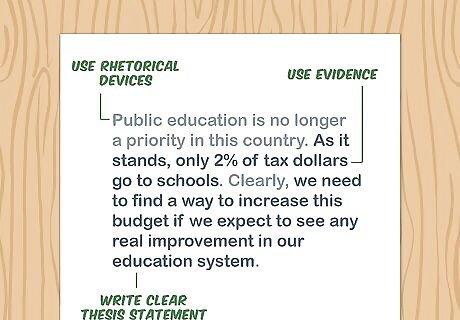

Write an introduction. Many people believe that your introduction is the most important part of the essay because it either grabs or loses the reader's attention. A good introduction will tell the reader just enough about your essay to draw them in and make them want to continue reading. Put your hook first. Then, proceed to move from general ideas to specific ideas until you have built up to your thesis statement. Don't slack on your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is a short summary of what you're arguing for. It's usually one sentence, and it's near the end of your introductory paragraph. Make your thesis a combination of your most persuasive arguments, or a single powerful argument, for the best effect.

Structure your body paragraphs. At a minimum, write three paragraphs for the body of the essay. Each paragraph should cover a single main point that relates back to a part of your argument. These body paragraphs are where you justify your opinions and lay out your evidence. Remember that if you don't provide evidence, your argument might not be as persuasive. Start with a clear topic sentence that introduces the main point of your paragraph. Make your evidence clear and precise. For example, don't just say: "Dolphins are very smart animals. They are widely recognized as being incredibly smart." Instead, say: "Dolphins are very smart animals. Multiple studies found that dolphins worked in tandem with humans to catch prey. Very few, if any, species have developed mutually symbiotic relationships with humans." When you can, use facts as your evidence. Agreed-upon facts from reliable sources give people something to hold onto. If possible, use facts from different angles to support one argument. For example: "The South, which accounts for 80% of all executions in the United States, still has the country's highest murder rate. This makes a case against the death penalty working as a deterrent." "Additionally, states without the death penalty have fewer murders. If the death penalty were indeed a deterrent, why wouldn't we see an increase in murders in states without the death penalty?" Consider how your body paragraphs flow together. You want to make sure that your argument feels like it's building, one point upon another, rather than feeling scattered.

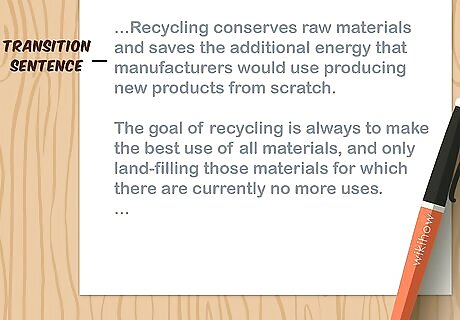

Use the last sentence of each body paragraph to transition to the next paragraph. In order to establish flow in your essay, you want there to be a natural transition from the end of one paragraph to the beginning of the next. Here is one example: End of the first paragraph: "If the death penalty consistently fails to deter crime, and crime is at an all-time high, what happens when someone is wrongfully convicted?" Beginning of the second paragraph: "Over 100 wrongfully convicted death row inmates have been acquitted of their crimes, some just minutes before their would-be death."

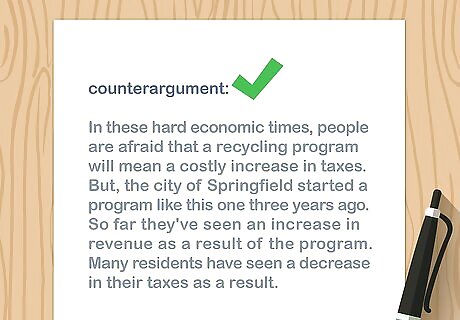

Add a rebuttal or counterargument. You might not be required to do this, but it makes your essay stronger. Imagine you have an opponent who's arguing the exact opposite of what you're arguing. Think of one or two of their strongest arguments and come up with a counterargument to rebut it. Example: "Critics of a policy allowing students to bring snacks into the classroom say that it would create too much distraction, reducing students’ ability to learn. However, consider the fact that middle schoolers are growing at an incredible rate. Their bodies need energy, and their minds may become fatigued if they go for long periods without eating. Allowing snacks in the classroom will actually increase students’ ability to focus by taking away the distraction of hunger.” You may even find it effective to begin your paragraph with the counterargument, then follow by refuting it and offering your own argument.

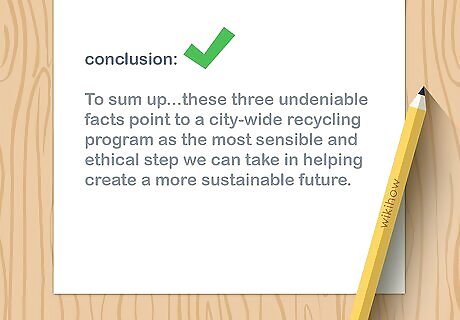

Write your conclusion at the very end of your essay. As a general rule, it's a good idea to restate each of your main points and end the whole paper with a probing thought. If it's something your reader won't easily forget, your essay will have a more lasting impression. Don’t just restate the thesis; think about how you will leave your reader. Here are some things to consider: How could this argument be applied to a broader context? Why does this argument or opinion mean something to me? What further questions has my argument raised? What action could readers take after reading my essay?

How to Write Persuasively

Understand the conventions of a persuasive essay. Unless your prompt or assignment states otherwise, you’ll need to follow some basic conventions when writing your persuasive essay. Persuasive essays, like argumentative essays, use rhetorical devices to persuade their readers. In persuasive essays, you generally have more freedom to make appeals to emotion (pathos), in addition to logic and data (logos) and credibility (ethos). You should use multiple types of evidence carefully when writing a persuasive essay. Logical appeals such as presenting data, facts, and other types of “hard” evidence are often very convincing to readers. Persuasive essays generally have very clear thesis statements that make your opinion or chosen “side” known upfront. This helps your reader know exactly what you are arguing. Bad: The United States was not an educated nation, since education was considered the right of the wealthy, and so in the early 1800s Horace Mann decided to try and rectify the situation.

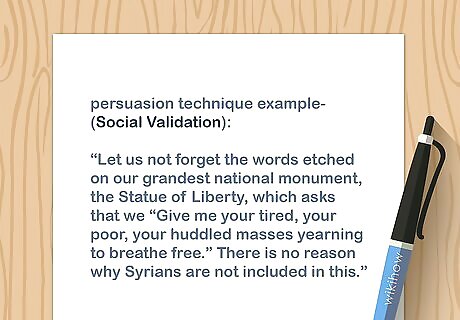

Use a variety of persuasion techniques to hook your readers. The art of persuasion has been studied since ancient Greece. While it takes a lifetime to master, learning the tricks and tools will make you a better writer almost immediately. For example, on a paper about allowing Syrian refugees, you could use: Pathos, Ethos, and Logos: These are the 3 cornerstones of rhetoric. Pathos is about emotion, ethos is about credibility, and logos is about logic. These 3 components work together to help you develop a strong argument. For example, you could tell an anecdote about a family torn apart by the current situation in Syria to incorporate pathos, make use of logic to argue for allowing Syrian refugees as your logos, and then provide reputable sources to back up your quotes for ethos. Repetition: Keep hammering on your thesis. Tell them what you're telling them, tell them it, then tell them what you told them. They'll get the point by the end. Example: Time and time again, the statistics don't lie -- we need to open our doors to help refugees. Social Validation: Quotations reinforce that you aren't the only one making this point. It tells people that, socially, if they want to fit in, they need to consider your viewpoint. Example: "Let us not forget the words etched on our grandest national monument, the Statue of Liberty, which asks that we "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” There is no reason why Syrians are not included in this. Agitation of the Problem: Before offering solutions, show them how bad things are. Give them a reason to care about your argument. Example: "Over 100 million refugees have been displaced. President Assad has not only stolen power, he's gassed and bombed his own citizens. He has defied the Geneva Conventions, long held as a standard of decency and basic human rights, and his people have no choice but to flee."

Be authoritative and firm. You need to sound an expert, and like you should be trustworthy. Cut out small words or wishy-washy phrase to adopt a tone of authority. Good: "Time and time again, science has shown that arctic drilling is dangerous. It is not worth the risks environmentally or economically." Good: "Without pushing ourselves to energy independence, in the arctic and elsewhere, we open ourselves up to the dangerous dependency that spiked gas prices in the 80's." Bad: "Arctic drilling may not be perfect, but it will probably help us stop using foreign oil at some point. This, I imagine, will be a good thing."

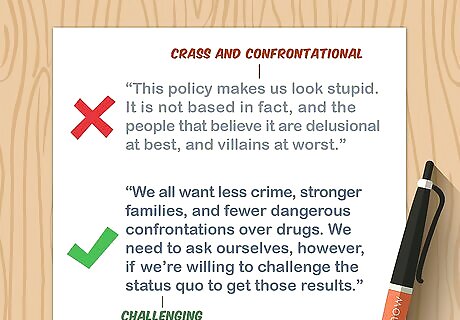

Challenge your readers. Persuasion is about upending commonly held thoughts and forcing the reader to reevaluate. While you never want to be crass or confrontational, you need to poke into the reader's potential concerns. Good: Does anyone think that ruining someone’s semester, or, at least, the chance to go abroad, should be the result of a victimless crime? Is it fair that we actively promote drinking as a legitimate alternative through Campus Socials and a lack of consequences? How long can we use the excuse that “just because it’s safer than alcohol doesn’t mean we should make it legal,” disregarding the fact that the worst effects of the drug are not physical or chemical, but institutional? Good: We all want less crime, stronger families, and fewer dangerous confrontations over drugs. We need to ask ourselves, however, if we're willing to challenge the status quo to get those results. Bad: This policy makes us look stupid. It is not based in fact, and the people that believe it are delusional at best, and villains at worst.

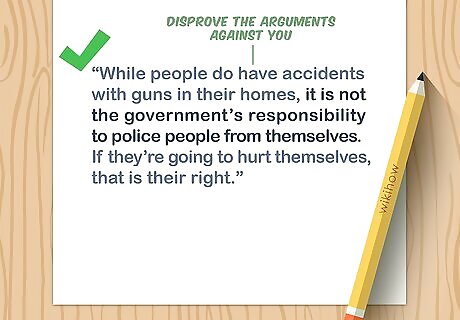

Acknowledge, and refute, arguments against you. While the majority of your essay should be kept to your own argument, you'll bullet-proof your case if you can see and disprove the arguments against you. Save this for the second to last paragraph, in general. Good: While people do have accidents with guns in their homes, it is not the government’s responsibility to police people from themselves. If they're going to hurt themselves, that is their right. Bad: The only obvious solution is to ban guns. There is no other argument that matters.

How to Polish Your Essay

Give yourself a day or two without looking at the essay. If you've planned ahead, this won't be hard. Then, come back to the essay after a day or two and look it over. The rest will give you a fresh set of eyes and help you spot errors. Any tricky language or ideas that needed time might be revisited then.

Read through your draft. A common error with many student writers is not spending enough time revisiting a first draft. Read through your essay from start to finish. Consider the following: Does the essay state its position clearly? Is this position supported throughout with evidence and examples? Are paragraphs bogged down by extraneous information? Do paragraphs focus on one main idea? Are any counterarguments presented fairly, without misrepresentation? Are they convincingly dismissed? Are the paragraphs in an order that flows logically and builds an argument step-by-step? Does the conclusion convey the importance of the position and urge the reader to do/think something?

Revise where necessary. Revision is more than simple proofreading. You may need to touch up your transitions, move paragraphs around for better flow, or even draft new paragraphs with new, more compelling evidence. Be willing to make even major changes to improve your essay. You may find it helpful to ask a trusted friend or classmate to look at your essay. If s/he has trouble understanding your argument or finds things unclear, focus your revision on those spots.

Proofread carefully. Use the spell checker on your computer to check the spellings of the words (if applicable). Read through your essay aloud, reading exactly what is on the page. This will help you catch proofreading errors. You may find it helpful to print out your draft and mark it up with a pen or pencil. When you write on the computer, your eyes may become so used to reading what you think you’ve written that they skip over errors. Working with a physical copy forces you to pay attention in a new way. Make sure to also format your essay correctly. For example, many instructors stipulate the margin width and font type you should use.

Comments

0 comment