views

X

Research source

Sending a Dispute Letter

Gather information about the transaction. Before you do anything, get all the documentation you have regarding the transaction – including receipts, confirmation emails, and shipping notifications – and make copies to share with the merchant. You want to be able to explain to the merchant exactly what the problem is and how you'd like it resolved. If you want a refund because the product you received was faulty or defective in some way, or arrived broken, you might want to take pictures of it. This could be helpful to your case assuming the damage is something visible. You also might want to take a screen capture of the listing on the merchant's website, if the image or description is related to your dissatisfaction. For example, if you bought pink curtains for your daughter's bedroom, and the curtains you received were black, the item description proves the item you received was different from the item you purchased. You'll also need to find out where to send a dispute letter and, ideally, the name of a person to whom you can address it. Typically you can find at least a contact address on the merchant's website. The website of the secretary of state in the state where the business is physically located may have an address and the name of the merchant's legal agent, if the business is incorporated.

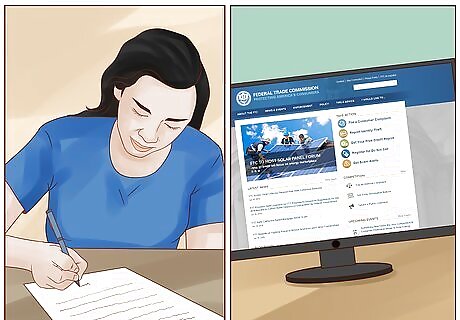

Draft your dispute letter. Assuming you've been unable to resolve the dispute with the merchant either over the phone or online, compose a written letter describing your problems with the transaction. Government and consumer protection agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have sample dispute letters on their websites that you can use as guides. Follow the sample letters as a basic template, but be sure to adapt them to your situation – don't just copy something verbatim that doesn't apply to your dispute. Provide as much factual detail about the transaction and your dispute as possible, and attach copies of all emails and other documents for proof. Include information such as transaction or customer account numbers so the merchant can quickly find the transaction you're disputing. Tell the merchant exactly what you want to happen to resolve the dispute. Include specific contact information so the merchant can respond, and give him or her a deadline. Although you probably want the issue resolved as quickly as possible, be sure to set the deadline out far enough that the merchant has time to investigate your transaction – a couple of weeks after receipt of your letter is plenty.

Send your dispute letter to the merchant. Once you've finalized your letter, make a copy of it for your records and then mail it to the merchant along with any evidence you've collected. Use certified mail with returned receipt requested so you know when the merchant gets your letter. When you get the receipt back letting you know that the merchant has received your letter, mark the date of the deadline you gave the merchant on your calendar. If you don't receive a response by that date, you're clear to go forward.

Wait for a response. How the merchant responds to your formal letter may dictate the next steps you take. If the merchant agrees to your demands, you may not have to file a lawsuit at all. However, if the merchant is unwilling to work with you, you may have to file a lawsuit if you want your money back. Keep in mind your letter may go to someone higher up the chain of command than anyone you talked to at the business's customer service number, so you may get an entirely different response than you were expecting. The merchant may call you, but typically they'll respond to a written letter in writing. If they reject your argument, their response should outline their reasons. If the merchant agrees to work with you to resolve the matter, make sure you get any agreement in writing. If the merchant doesn't follow through on what they agreed to do, you can use the written letter to enforce the agreement.

Consider filing an administrative complaint. Regardless of the outcome of the situation after you send your dispute letter, you can file a complaint with consumer protection agencies such as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) or the Better Business Bureau (BBB). If your dispute letter doesn't resolve the issue, a complaint to the CFPB can bring the government to bat on your behalf. Other complaint agencies such as the BBB not only rate the business, but make consumer complaints public to provide notice of past disputes to potential customers checking out the company's reputation. When filing complaints, stick to the facts and avoid insulting the business or any of the individuals with whom you spoke. Simply relate what happened in an objective manner. If the complaint will be public, you may include a statement to the effect that you would not recommend doing business with the company, but refrain from hyperbole or personal insults.

Initiating a Lawsuit

Determine if you can sue in small claims court. Before you file a lawsuit in small claims court, you must make sure that the amount of money involved in the dispute is below the limit established by your state for small claims, and that the court will have jurisdiction over the merchant. Generally you can only sue in small claims court for money, which means you can't get a court order for the merchant to replace faulty merchandise or the like – you can only get your money back. Each state has a maximum limit of money you can ask for in small claims, which varies from $2,500 to $10,000. Keep in mind that if your claim is worth more than your state's maximum for small claims, you typically can't keep your case in small claims by only asking for that maximum limit. The judge will throw the case out or move it to county civil court if the claim is actually worth more. In addition to the claim limit, you must establish that the court has personal jurisdiction over the defendant – the merchant you're suing. This can be tricky with disputes over internet transactions. You must be able to demonstrate that the merchant regularly does business in your state. Generally you can prove this by showing that the merchant sells products or services directly, knew the state in which you lived when the transaction took place, and does a lot of business in your state. Check your secretary of state's website and search the online directory of regular businesses for the merchant you want to sue. If the merchant is registered to do business in your state and has an agent for service of process, you should be okay on the personal jurisdiction issue. Even if the business isn't licensed in your state, the court still may have personal jurisdiction, but this is likely something the judge will have to decide based on the totality of the circumstances surrounding your transaction.

Fill out your claim forms. The small claims court in your county will have specific forms that you must fill out and file with the clerk of court to initiate a lawsuit. These forms require information about you and the merchant you want to sue, as well as details about the dispute. You typically can get copies of these forms from the small claims court clerk – you just have to make a trip to the courthouse. While you're there, you can find out how much the filing fees are to start a small claims case. You also may be able to download small claims forms online at the court's website. If there is no date on the forms, call the clerk's office and make sure the forms you find online are up to date. You must have the correct name and address of the merchant's registered agent for service of process, as well as the correct legal name of the merchant. Typically you can find this information online. If the merchant isn't registered to do business in your state, check the secretary of state's website of the state where you sent your dispute letter. Describe the dispute in detail and provide an exact dollar amount of damages you're asking the court to award you. You may be able to attach documents you intend to introduce as evidence. Once you've completed your forms and signed them, make at least two copies. One will be for your records and the other will be to send to the merchant.

File your claim forms. Take your completed original forms and your copies to the clerk of the small claims court that you want to hear your case. You must pay a filing fee to the clerk, typically $100 or less for a small claims case. If you can't afford the filing fees, ask the clerk for a waiver application. You must provide details about your income and assets. If these fall below the court's threshold, you typically will be granted a waiver. Most courts grant fee waivers automatically for people on public assistance. The clerk will stamp your originals and copies "filed" with the date, and give the copies back to you. After asking you a few questions about your claim, the clerk likely will schedule the date of your hearing.

Have the merchant served. The judge won't hear your case unless the merchant has received proper legal notice of the lawsuit and has the opportunity to respond and defend themselves in court. You must follow the proper procedure – called "service" – to have the documents delivered to the merchant. Technically anyone over the age of 18 who is uninvolved with the case can complete service. However, you might want to use a professional to ensure the process is completed correctly. Typically you get a sheriff's deputy to hand-deliver the court documents to the merchant's registered agent in your state. If the merchant doesn't have a registered agent in your state and is located far away, your simplest method may be to mail the papers using certified mail with returned receipt requested. The notice you get that the documents were received will serve as proof, and you'll have to fill out a proof of service document to submit to the court.

Wait for a response. When the merchant is served, they have a limited period of time to respond to your lawsuit or you may be eligible to win by default. In a small claims case, this may mean filing a written response, or showing up for an initial hearing. If a written response is required, the papers delivered to the merchant typically will include an answer form for the merchant to fill out and return to the court. You will receive a copy of the answer as well. The merchant's response may include various defenses, or a counterclaim against you. These issues will be discussed at your court hearing, so you'll need to look over them and plan your arguments against them. Keep in mind the merchant likely will have an attorney, so you may want to consult with an attorney at some point before your hearing. Typically attorneys can't represent people in small claims court, but your state may require corporations to have attorneys, or may allow you to be represented by an attorney if there's one on the other side. Even if you aren't allowed to have an attorney represent you, there's nothing wrong with talking to someone and getting their opinion on how to proceed with your case.

Attending Your Hearing

Organize your documents and other evidence. Outline your argument before the hearing and make sure you have at least three copies of any documents you plan to introduce as evidence at your hearing. You'll make a better impression on the judge if you are prepared and organized. Go over the outline of your presentation several times. You can practice in front of a mirror or even in front of a friend or family member. If your dispute centers around the fact that the product you purchased was damaged or defective, you may want to consider bringing it to court with you – as long as it's small enough to carry easily and is not something that would be prohibited in the courthouse. With an internet transaction, it's unlikely you'll have witnesses, but if you do, you typically are allowed to bring them with you to testify on your behalf. For example, if you purchased the product as a gift for someone else and it malfunctioned or never arrived, that person may be a witness for you. Similarly, if your spouse was present during the transaction and witness to the problem, he or she might be willing to testify on your behalf.

Appear on your court date. Get to the courthouse at least a half hour before your hearing is scheduled so you have time to get through security and find the right courtroom. You also want to leave yourself plenty of time so you aren't rushed. You don't necessarily have to wear a suit to go to court, but you do want to wear clean and neat attire. If you're unsure about your ensemble, select something you would wear on a job interview. The court likely has a document that lists the items that are not allowed in the courthouse. Check this list and make sure you're not bringing anything with you, such as a pocket knife or a mobile phone, that may be confiscated by security. When you get to your courtroom, take a seat in the gallery. The judge likely will be hearing several cases that day, so wait until your name and case are called before you move to the tables at the front of the courtroom.

Present your case to the judge. Since it's your lawsuit, you typically will have the opportunity to speak to the judge first. You must tell him about the dispute, why you think the judge should order the merchant to pay you money, and how much money that should be. Use the outline you've prepared, and speak in a loud, clear voice so the judge can hear and understand you. Speak directly to the judge – don't address the merchant. If the judge asks you any questions, stop speaking immediately and answer the judge's question. When the judge indicates that he or she is satisfied with your answer, you may pick up where you left off in your outline. If you have any witnesses, introduce them by their legal name and call them to the stand. They will be sworn in and then you can begin asking them questions. The judge also may have questions for your witnesses, and they will be subject to cross-examination from the merchant. If the merchant has not appeared at the hearing, you may be eligible to win your case by default. However, you typically still must prove that you're entitled to the amount of damages for which you've asked.

Listen to the merchant's presentation. After you've finished telling the judge about the dispute, the merchant will have the opportunity to explain his or her side of the story, including the discussion of any defenses or counterclaims against you. Keep in mind that the merchant likely will say things you don't agree with – they might even say things you know are not true – but it's important not to interrupt or shout out. Trust that the judge will get to the truth of the matter. You also should be aware of your body language and facial expressions. These can reveal your attitude and make a bad impression. Focus on maintaining a "poker face." Typically you'll have the opportunity to speak again after the merchant is done, so if they say anything that you want to talk about, write it down so you don't forget.

Receive the judge's ruling. After the judge has listened to both you and the merchant, he or she will make a decision as to whether you are entitled to any money as a result of the dispute, and how much your award will be. Typically, a judge makes his ruling from the bench in a small claims case. However, you may have to wait a few days for the written order. If you win your case, take the written order to the clerk's office when you receive it to find out the process for enforcing the order. Just because you win doesn't mean you automatically get your money – you're only entitled to collect it. You usually have to wait a period of time – from two weeks to 30 days – after the order is issued before you can enforce it, since the merchant may opt to appeal. If the judge rules against you, ask the judge or the court clerk what you have to do to appeal the decision.

Comments

0 comment